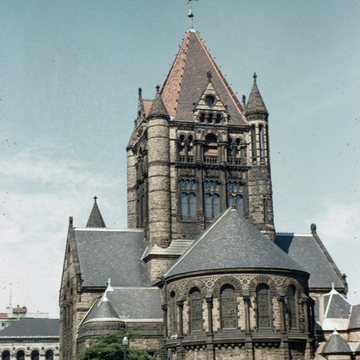

Serene and powerful, Trinity Church surveys its substantial architectural rivals encircling Copley Square. One of the most celebrated of Boston buildings and one of the first American buildings to attract attention abroad, Trinity was voted the finest work of American architecture in an 1886 poll conducted by The American Architect and Building News. A century later, it remained the only building from this initial top ten to survive in a similar contest sponsored by the American Institute of Architects.

Henry Hobson Richardson, a young New York architect with useful connections from his Harvard years, won the right to design Trinity Church in a select competition with seasoned professionals. His unique response to the conditions of an awkward site produced both the first prize and the design that would make his career. Here he refined his use of French Romanesque forms as the basis for a very personal style. The Reverend Phillips Brooks, Trinity's rector, had convinced his Episcopal parish to move to the Back Bay even before the Great Boston Fire of 1872 destroyed their previous building on Summer Street. Richardson devised a plan that accommodated both the church and a parish house on a triangular plot at the southeastern edge of the then ill-formed Copley Square.

The church was constructed of Quincy, Dedham, Westerly, and Rockport granite trimmed with Longmeadow brownstone, combining decorative sources from the French Romanesque with a more liberal fenestration for the masonry walls. For such a landmark building, the engineering was surprisingly conservative, yet dramatic. The multiple-ton weight of the structure is set on a forest of 4,500 wooden piers pounded into gravel fill and secured through the swelling caused by a high water table. The principal engineering thrust of the large crossing tower, inspired by the Romanesque cathedral at Salamanca, Spain, is distributed to four massive piers supported below grade on granite stepped pyramids, forty feet square at the base by twenty feet high, that rest on the pilings.

Among Episcopal parishes, Trinity was quite a broad church, emphasizing preaching over the sacraments. Richardson accommodated this need with an exceptionally open auditorium for Brooks, who preached from a small lectern at the front center of the apse,

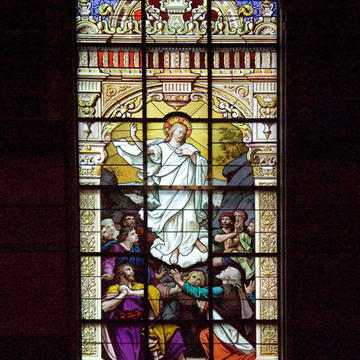

Beyond the walls, Trinity sparkles with one of the finest collections of American and European stained glass in this country. La Farge produced five windows for Trinity Church, including the dazzling effects of his Christ in Majesty lancets at the western end. In contrast are the rich warm greens of English stained glass artist Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris and Company in the north transept and the cool blue architectural settings of French artist Achille François Oudinot's south transept windows. The less dramatic work of Englishmen Clayton and Bell fill the arched windows of the apse. Worth the search are the windows by Boston women artists—the nave aisle windows by Margaret Redmond and the Phillips Brooks memorial window in the parish house library by Sarah Wyman Whitman.

Trinity Church has been considerably enriched by additions following Richardson's early death in 1886. His successor firm, Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge, added the west porch (1894–1897), following his general intentions but relying more heavily on the model of St. Trophime, a Romanesque church in Arles, France. In 1914, they created the massive sculptural pulpit and sounding board, given as a memorial to Robert Treat Paine, chairman of the original building committee, by his children. As this parish moved toward a more ceremonial form of worship, a campaign to enrich the apse in 1937 produced the Byzantine-inspired decoration in gilt stucco, marbles, and mosaics at the lower level of the apse; the great altar; and the hanging cross, all to designs by the leading Roman Catholic architects Maginnis and Walsh. In 2003, the church launched a major restoration and expansion, excavating the undercroft for additional social and educational spaces. As the focal point of Copley Square, Trinity Church remains one of the dominant architectural icons of Boston.