The dynamic main library for the city of Seattle landed downtown with much fanfare in 2004, and perhaps for good measure. A well-used downtown building, the Seattle Central Library has earned several awards, appeared in revised versions of leading textbooks on global architectural history, and raised important questions about the nature of the library in the information age—before the meteoric rise of social media, the smart phone, and Google. Often noted for its collaborative, communally oriented design process, the library is considered one of the few buildings to place Seattle firmly on the international architectural map.

The library has not, however, escaped the critical eye of the public or the architectural press. The oddly shaped structure, with its diamond-shaped exterior grid of steel and glass, bears little resemblance to its neighbors; it inverts the traditional functions of the street as a place for public assembly and consumption by bringing these functions inside; and its unconventional internal organization makes for difficult wayfinding and circulation, even if such challenges were intentional. Envisioned by the design team as a library for the “digital age” for an increasingly tech-savvy and consumer-driven public, the building, whose design was led by the Rotterdam-based Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) and its principal architects Rem Koolhaas and Joshua Prince-Ramus, may have forecast its own obsolescence. The seemingly infinite expansion of virtual space and shifting notions of public libraries as community centers in the years since its construction may ultimately render the Seattle Central Library as a period piece, suspended in abeyance between two historical periods. Its longevity, if not its legacy, remains uncertain.

Such uncertainty would be in keeping with the history of library buildings on this sloping site, bounded by Fourth and Fifth avenues and Madison and Spring streets just south of Seattle’s financial district. The 2004 building is the third downtown library since 1906, its previous incarnations finding themselves lacking adequate space or, in 1946, following an “unsightly and inadequate” addition to the original 1906 Carnegie library, lacking aesthetics. Another new building constructed in 1960 and expanded in 1979 served downtown reasonably well until the 1990s, when it too began to run out of room. The city passed a $196 million bond measure in 1998 to build yet another new library at the site, in addition to doubling the square footage of Seattle’s branch libraries. At the time, this was the largest bond measure approved for city libraries in U.S. history.

Such an enormous outlay of taxpayer money generated considerable interest in the new library’s design, as well as the selection of its designers. The awarding of the commission to OMA emerged following a three-day public design competition held in December 1999 at Seattle’s Benaroya Hall, attended by approximately 1,500 people, including Seattle’s design selection board and members of Seattle’s design community. Apparently due in part to Koolhaas’s extraordinary presentation skills, OMA bested New York–based Steven Holl Architects, led by the Washington native Holl, who received his Master of Architecture degree from the University of Washington.

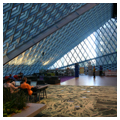

The 11-story, over 350,000-square-foot Seattle Central Library opened in May 2004 at a cost of almost $170 million, its unusual form rising amidst a series of stately, modernist, high-rise office towers and public buildings. Those designs were characterized by efficiency and elegance, not dynamism and change: even the boxy, dark steel and glass tower to the west, built originally for the Seattle-First National Bank, was buttoned-up and formal to the letter. In this context, the new, light-filled library with its diamond-shaped exterior grid was rather striking, though the building reaches out to its context in particular ways. This includes a broad, open plaza under a pronounced overhang at the Fourth Avenue entrance and a slanted, open-latticed structure forming an arcade over the Fifth Avenue sidewalk. From the library’s upper floors, views to Elliott Bay, the Olympic Mountains, and to Seattle unfold in all directions. Designers claimed that the library’s curtain wall of angled glass was dictated not by a desire for eccentricity but to respond to views and daylight.

With its receding and jutting planes and surfaces, the building is intended to reflect its internal programming. While not obvious to the casual passerby, OMA attempted to define the building’s exterior as a series of stacked platforms or volumes, each suggesting a separate function, whether the broad, sloping glass wall for the “living room” on the lower levels or the flat, multi-story surface suggesting the upper-floor book spiral. To help visually explain the form, OMA built a competition model, based upon an oft-reproduced diagram, showing the building’s essentially five fixed volumes extruded in an exaggerated fashion: parking, staff offices, meeting rooms, book stacks, and library administration. The more programmatically flexible spaces would fill the gaps: the living room, a children’s area, and a reading room to accompany what OMA called the public “mixing chamber,” which featured the majority of the library’s desktop computers. The building’s facade also serves a structural capacity, providing lateral support to brace against wind and seismic forces; the building’s heavy vertical loads are carried by steel columns. A metal mesh, sandwiched between glass on the side panels that receive the most sun during the year, protects against heat gain and glare without compromising the library’s openness and transparency.

Whether the building’s functions are apparent from the exterior is obviously less crucial than its use as a library. Even with the rise of online books, the designers worked to ensure printed books remained central to the library—not as afterthoughts for an allegedly vanishing medium. Prior to construction, Koolhaas, Prince-Ramus, and Seattle Library Director Deborah Jacobs researched and visited several urban libraries and consulted with experts on library design and digital technology. Their investigations revealed that people perceived library architecture, in general, as old-fashioned, pretentious, and uninviting, but their research convinced them that the design still must incorporate actual, physical books.

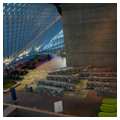

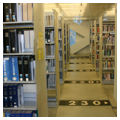

To ensure that books retained a vaunted place within their design without sacrificing a desire to provide exciting, innovative spaces, the designers showcased the fiction collection in angled bookshelves in the most easily accessible areas in the third-floor “living room” and the non-fiction collection in a continuous “book spiral,” a series of switchback ramps from floors six through nine that are accessible via a long, illuminated, chartreuse escalator. Rather than separating volumes on stacked floors organized by subject matter, the book spiral contained books organized by the Dewey decimal system, beginning at 000 on the lowest level and twisting to 999 at the top. Koolhaas hoped the spiral would be just one of several architectural moves intended to create a more active, “walking experience” that countered the “sadness” of traditional libraries. To further enliven the overall experience, the design team jazzed up the flexible, interstitial spaces with a startling array of colors, furniture, and names (the aforementioned living room and mixing chamber were part of what Koolhaas referred to as the building’s “trading floors”), providing both a contemporary flavor and references to familiar, physical spaces where human interaction is paramount.

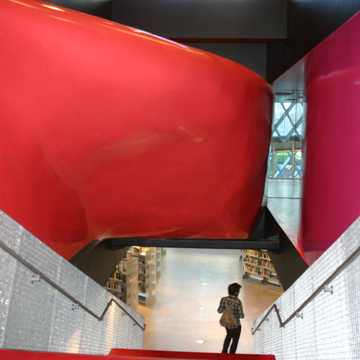

Patrons enter the library from one of two entrances. The west-facing Fourth Avenue entrance brings patrons into the library’s ground floor, which includes a dedicated space for children, the ground-floor entrance to a 275-seat auditorium, and one of the building’s glowing chartreuse escalators—this one carrying patrons to the third-floor living room. The east-facing Fifth Avenue entrance, on higher land, brings patrons directly into the cavernous living room, with its array of furniture and books beneath a dramatic, slanted glass ceiling. A cafe accommodates patrons on the north side of the floor, while expansive interior views lead to a massive concrete support along the west wall and more chartreuse escalators leading to the fifth-floor reference area and mixing chamber. It is here, in this space, where the grand theater of urban life finds its most open, diverse, and dramatic expression—what Architectural Record writer Sheri Olson, upon the library’s 2004 opening, declared Seattle’s “most inviting public space.” Library-goers who choose not to linger in the living room might wander to the northern edge, where bright red stairs, amorphously shaped walls, and ceilings beckon patrons into an amphibious environment, signaling the level of meeting rooms. Those who continue towards the fifth-floor mixing chamber encounter a strikingly different mood: dark furniture, a black-painted ceiling, and regimented rows of computers line up near a massive reference desk resembling the command center of a spaceship.

The tenth floor, which contains the library’s special collections on the south and spaces for reading and studying on the north, offers spectacular views to the urban and natural environment. It also provides close-up views of the building’s exoskeleton, and features a padded ceiling made of fiberglass and nylon to assist with acoustics. Typical of many OMA projects, some materials are raw, prosaic, and inexpensive, yet combined or treated in ways to be provocative, didactic, or, at times, alluring: flooring on different levels, for example, is made of aluminum, poured concrete, recycled wood, or bamboo, and columns and beams in the mixing chamber feature dangling pipes and are covered with what seems to be randomly applied fireproofing. Exposed structural beams and columns are everywhere present.

Not all design decisions were made by OMA. Although it remains unclear how many, or which, suggestions from the public were ultimately taken into account in the final design, the library did feature a lengthy public process and, perhaps due to the Dutch architects’ overseas office location, much work was left to the local team of Loschky, Marquardt and Nesholm (LMN) Architects, Magnusson Klemencic Engineers, and Hoffmann Construction, who were compelled to translate OMA’s drawings into reality. Many important decisions were made by the project’s principal clients, as well: Jacobs and Betty Jane Narver, the president of the library board. It was Jacobs who apparently convinced OMA not to employ the green, unfinished sheetrock that it had provided on other projects, in part because she considered it important that the library, as a public building, convey a sense of awe.

Awesome or not, the architecturally unorthodox library was not met without controversy and criticism. Local critics and architects, still reeling from what they considered the high-profile aesthetic disasters of Robert Venturi’s Seattle Art Museum and Frank Gehry’s Experience Music Project, seethed at the proposal. Seattle Times’ columnist Susan Nielsen compared it to a rabbit cage, and thought Koolhaas might someday realize that he designed “the ugliest library in the world.” Beyond aesthetics, the library was critiqued for a failure to physically reach the public: its north and south sides met the streetline with a deadening monotony, and its east and west sides provided little in the way of urban vitality save for open space, bike racks, and minimal landscaping. The library also was quickly castigated for a lack of elevators, escalators that stop only on selective floors, and puzzling circulation—circumstances that might have been alleviated by a more generous budget. Complaints of small, infrequently maintained bathrooms abound, as do the usual elitist laments about having to share space with the city’s homeless. The building has also been labeled as too high-minded, requiring an advanced degree to unpack.

The library has nonetheless remained extraordinarily popular. Beyond an irregular stream of tourists, it is typically filled with locals—not all of whom are there to seek shelter from Seattle’s consistent drizzle. Designed to honor the venerable tradition of the book and places of public assembly while teetering on the cusp of a global internet explosion, the Seattle Public Library has arguably emerged as one of the most important buildings of the twenty-first century. Changes in culture may spread faster than the physical space of the library can accommodate, but the building will be no less important for its attempt to account for them. It should also remain a worthy example of how a collaborative design process can result in a dazzling design: one that raises questions about the nature of the city and the place of architecture within it.

References

Cheek, Lawrence. “On Architecture: New Library is Defining Seattle’s Urban Vitality.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, June 27, 2005.

Goldberger, Paul. “High-Tech Bibliophilia: Rem Koolhaas’s New Library in Seattle is an Ennobling Public Space.” New Yorker, May 24, 2004.

Hackett, Regina. “Seattle Central Library: Design is Fun on a Grand Scale.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 19, 2004.

“History of the Seattle Central Library.” The Seattle Public Library. Accessed October 13, 2017. http://www.spl.org/.

Jencks, Charles, and Rem Koolhaas. “Radical Post-Modernism and Content: Charles Jencks and Rem Koolhaas Debate the Issue.” Architectural Design 81, no. 5 (September 2011).

Mattern, Shannon. “Just How Public Is the Seattle Central Library? Publicity, Posturing, and Politics in Public Design.” Journal of Architectural Education 57, no. 1 (September 2003): 5-18.

Murphy, Amy. “Seattle Central Library: Civic Architecture in the Age of Media.” Places Journal (December 2006).

Muschamp, Herbert. “The Library That Puts on Fishnets and Hits the Disco.” New York Times, May 16, 2004.

Olson, Sheri. “Thanks to OMA’s Blending of Cool Information Technology and Warm Public Spaces, Seattle’s Central Library Kindles Book Lust.” Architectural Record (July 2004): 88-101.

Rahner, Mark. “Talking with Rem Koolhaas, the Architect Behind the Central Library.” Seattle Times, September 9, 2008.

“The Making of a Library.” Metropolis (October 2004): 97-115.