You are here

Coeur d’Alene’s Old Sacred Heart Mission

The Coeur d’Alene’s Old Sacred Heart Mission, with its prominent Baroque facade, stands majestically on a hill facing Interstate 90 in northern Idaho, intriguing travelers who might wonder why a formal work of architecture was built in such a remote location. A century ago the mission captivated motorists on the preceding two-lane road as it did settlers, miners, and soldiers along the nineteenth-century Mullan Road, and Indigenous people—by whom and for whom the mission was built—on one of their primary trails. The Old Sacred Heart Mission is the oldest building in Idaho and the oldest remaining mission church in the Pacific Northwest. It is a remarkable technical achievement given limited materials, tools, and skilled labor. Yet most extraordinary is the aesthetic power of the architecture, achieved through the design and artistic sensibilities of an Italian Jesuit, whose vision took form through the labor of Indigenous people and lay brothers. The mission was created as an awe-inspiring place for the spiritual development of Indigenous people known to themselves as the Schitsu’umsh and to French trappers and others as the Coeur d’Alenes.

The Sacred Heart Mission was the second Jesuit mission in the area. The first was St. Mary’s, established among the Flatheads in Montana in 1841 by Father Pierre-Jean De Smet. While traveling to procure supplies in 1842, De Smet met Coeur d’Alene chief, Twisted Earth, whose father, Chief Circling Raven, had in 1740 prophesied the coming of the “Blackrobes” (Jesuit missionaries) who would provide spiritual help for the Coeur d’Alene people. In response to a request from the Coeur d’Alenes, De Smet sent Father Nicholas Point and Brother Charles Huet to establish the Mission of the Sacred Heart along the St. Joe River near the southern end of Lake Coeur d’Alene. After repeated flooding at this site, in 1846 Point moved the mission to a hill overlooking the Coeur d’Alene River 27 miles east of the lake. When they arrived, Brother Huet built a temporary cedar-bark chapel.

After the chapel’s roof collapsed in 1847 and again in 1849, Father Antonio Ravalli, a priest stationed at St. Mary’s in Montana, began designing a new church. Ravalli was born in Ferrara, Italy, where he learned construction skills such as woodworking, stone dressing, and bricklaying. He apprenticed himself to an artist and a mechanic in preparation for becoming a priest and missionary. Ravalli saw a wide range of ecclesiastical art and architecture in and around Ferrara and as part of his theological education in Rome. He visited the Vatican and would certainly have seen the Jesuit mother church, Il Gesù. Ordained in 1843, Ravalli came to Montana with De Smet in 1845.

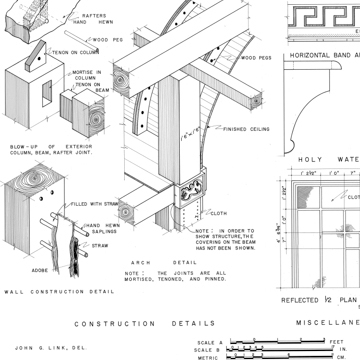

Working from Ravalli’s plans, Brother Vincent Magri, a Maltese joiner, began construction of the church before Ravalli arrived at the mission site in November 1850 to oversee construction. Construction materials were limited to those available locally—fieldstone, wood, grasses, and earth—and tools were limited to a broad axe, auger, rope, pulleys, and improvised whipsaw. Coeur d’Alene men, women, and children did most of the construction. Although described as “unskilled,” in fact, they had considerable experience in using local materials to construct their own buildings.

For the church’s foundation, Coeur d’Alene people quarried angular fieldstones, carried them up the hill, and placed them directly on the ground surface rather than in trenches. They gathered and mixed clay and water to mortar stones in place. They felled trees, floated them down the river, hauled them up the hill, and shaped them into sills, posts, and beams. People gathered local hemp and twisted its fibers into rope to use with pulleys; these were used to erect hand-hewn pine columns, measuring 22-28 inches square and 24 feet high, onto rectangular sills on the stone foundation and to raise two rows of 80-foot beams, one 14 feet above the sill and the other to the top of the columns. They mortised beams into columns and locked them in place with wooden pegs driven into auger holes. To make wattle and daub infill, workers (probably women) placed two rows of willow saplings horizontally between columns like wide ladders; they wove twisted bunches of wild grasses into the rows of willow saplings, thus forming cavity walls. Workers spread wet clay over the woven grasses and filled the cavity walls with clay. For the roof, the builders mortised and pinned pairs of 10-12 inch square rafters—joined with beams to create A-frame trusses—to the tops of columns. They attached shingles, likely shaved cedar shingles, to hand-hewn, 2-inch-thick boards serving as skip sheathing over the trusses.

Even in an unfinished state, the church awed travelers, astonished to see an imposing monument in what was then the hinterland of fledgling Washington Territory. The church was substantially complete by the fall of 1853 when Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens, passing by and spending the night, was so impressed that he directed his accompanying artist, John Mix Stanley, to draw it. In 1859 Father Joseph Joset noted that “if it were finished, it would be a handsome church even in Europe. . . . It is a great grief to us that we cannot finish it. . . . Without doors, windows, or flooring, and not being framed in on the outside, I fear it will rot before it is completed.” The wattle-and-daub walls were exposed until 1865 when Father Joseph Caruana lined the exterior with clapboard and the interior with wood paneling.

A curved Baroque pediment crowned by four urns and a cross dominates the facade. A radiant sunburst surrounding a circular window overlaid with the IHS Jesuit Christogram—similar to the sunburst and Christogram above the altar in the Jesuit mother church of Il Gesù—is applied to the center of the mission church’s pediment. Below the pediment is a Greek Revival portico with six Tuscan columns supporting an entablature embellished with a triglyph above each column. A Baroque false-front pediment above a Greek Revival portico may seem like an odd amalgamation. Yet it could be considered a more three-dimensional expression of the horizontal division found on facades of Baroque churches Ravalli would have seen such as Santa Maria in Vado in Ferrara or Il Gesù in Rome. What unifies these stylistically disparate elements of the mission church is the golden section proportion applied at different scales throughout the facade, including the proportion of the portico, false front gable, column spacing, and column pedestal faces.

From the portico, a pair of doors leads directly into the rectangular nave of the church. The semicircular apse, framed by cruciform columns supporting a shallow barrel vault, is capped by a wood-plank half dome. Flanking the apse is a pair of small rectangular chapels and behind each is a sacristy. When Caruana applied wood panels to the interior walls, he set them back from the columns and beams leaving clearly articulated structural bays within which windows are centered. Structural bays are also articulated in the ceiling by ornamental Baroque wood panels carved, assembled, and installed by Brother Francis Huybrecht working from Ravalli’s designs.

Interior decoration is eclectic and resourceful. Raised wood grapevines decorate column capitals framing the apse. Painted coffers articulate the half dome. A band of Greek key fretwork surrounds the base of the half dome and vault. Below that, printed fabric covers the walls. Although Jesuits had brought paintings from Rome to decorate the church, Ravalli painted others, and also created decorative furnishings and sculpture: he carved wood altars and painted them to simulate green, red, and white marble; he flattened, cut, and soldered tin cans to form candelabras and a fleur-de-lis crown over the altar; finally, Ravalli carved wood statues and painted them white to emulate marble statues he saw in Italy.

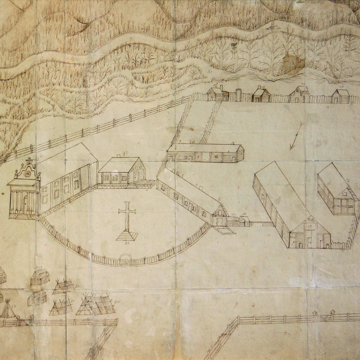

The Sacred Heart Mission was not just a church; it was planned as an agrarian mission village similar to previous Jesuit “reductions” in Paraguay. An 1860 sketch shows the entire mission complex with a total of 33 features, including the church, a large cross, parsonage, cabins, kitchen, traditional tule-mat and buffalo-hide lodges, various barns and sheds, a cemetery, and blacksmith, harness, carpenter, and bakers’ shops. Although Coeur d’Alene people had traditionally followed food resources throughout their territory, missionaries taught them to be sedentary farmers. Yet good farmland was limited at the mission’s location and became less available as settlers and miners moved into the area. In 1873 President Grant issued an Executive Order creating a reservation for the Coeur d’Alene people that excluded the mission. Consequently, in 1877, led by Father Alexander Diomedi, Coeur d’Alene people vacated the mission area. They migrated south to Desmet, where ample rich farmland was not yet claimed by settlers and where Diomedi established a new Mission of the Sacred Heart.

Father Joseph Cataldo, who had begun ministering to the Coeur d’Alenes in 1865, made the recently vacated mission his headquarters when he became Superior-General of the Rocky Mountain Missions in 1877; he stayed for the next decade. After that the church was rarely used, although in the 1880s the mission property supported a transportation hub connecting steamboats from Coeur d’Alene with trains to Wallace and other mining towns. The mission fell into disrepair, as would be expected with wood buildings that have had little maintenance. Though the building was repaired in 1884 by Father Joseph Joset and again in 1910 by Father Paul Arthuis, the Jesuits realized that they could not afford the ongoing maintenance. In 1924 they deeded the mission and its property to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Boise led by Bishop Gorman.

In 1925 Bishop Gorman initiated a funding campaign to restore the mission. With $12,000 raised, Boise architect Frederick Hummel and contractor James Lowery completed the restoration in 1929. One fundraising strategy involved publicized pilgrimages to the mission. For many people, especially Coeur d’Alenes, pilgrimages were meaningful spiritual endeavors that also celebrated history. More than 2,000 pilgrims participated in the 1926 automobile pilgrimage, including 90-year-old Father Cataldo and 200 Coeur d’Alene people led by Louis Michel. Tribal Elders included Theresa Benewah, Alice Yumas, Zachary, Timothy, and John Francis Regis (who had helped build the church), and Ajat Timothy, daughter of Chief Vincent.

In 1961, Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall, designated Old Mission a National Historic Landmark. Despite national recognition, the mission continued to deteriorate until 1973 when J. Meredith Neil, Executive Director of the Idaho Bicentennial Commission, chose the mission as the first restoration project to commemorate the bicentennial. Restoration architects Geoffrey Fairfax and Gerron Hite completed the $314,000 comprehensive restoration in 1975.

Also in 1975, the Diocese of Boise leased the Old Sacred Heart Mission to the Idaho Board of Parks and Recreation, establishing Old Mission State Park and ensuring the landmark’s preservation. In 2001 the Diocese deeded the mission and its property to the Coeur d’Alene Tribe. Ownership of the mission was a meaningful achievement for the Tribe, whose ancestors built and worshipped at the mission. As testament to the importance of the mission to Coeur d’Alene people, in 2011 the Tribe built a new $3.26 million visitor center to accommodate a permanent exhibit about the relationship between Jesuits and the Coeur d’Alene people and neighboring tribes. The relationship between Coeur d’Alene people and the mission endures; every year on August 15 the church comes alive as a spiritual place when members of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe make a pilgrimage to celebrate a special mass on the Feast of the Assumption.

The Coeur d’Alene’s Old Sacred Heart Mission continues to be one of the most impressive buildings in northern Idaho and a meaningful sacred site for Coeur d’Alene people. The drama of the systematically proportioned facade with a Baroque pediment and Greek Revival portico is enhanced by its striking contrast with the rugged landscape in which it was built. The great efforts undertaken by Coeur d’Alene people and Jesuits to transform native materials into a great work of architecture were all to move people spiritually and bring them closer to God. The Sacred Heart Mission is a post-Counter-Reformation recreation of an Italian Baroque church, a dramatic statement of Catholic faith built in undeveloped territory that would become the State of Idaho forty years later.

References

Ackerman, Lillian A. “The Effect of Missionary Ideals on Family Structure and Women’s Roles in Plateau Indian Culture.” Idaho Yesterdays 31, no. 1-2 (Spring-Summer 1987): 64-73.

Allen, Harold. Father Ravalli's Missions. Chicago: School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 1972.

Arrington, Leonard J. History of Idaho. Moscow: University of Idaho Press, 1994.

Attebery, Jennifer. Building Idaho: An Architectural History. Moscow: University of Idaho Press, 1991.

Bischoff, William N. The Jesuits in Old Oregon, 1840–1940. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers, 1945.

Carriker, Robert C. “Direct Successor to DeSmet: Joseph M. Cataldo, S.J., and the Stabilization of the Jesuit Indian Missions of the Pacific Northwest, 1877–1893.” Idaho Yesterdays 31, no. 1-2 (Spring-Summer 1987): 8-12.

Chittenden, Hiram Martin, and Alfred Talbot Richardson. Life, Letters and Travels of Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, 1801–1873. New York: F.P. Harper, 1905.

Cody, Edmund R. History of the Coeur d’Alene Mission of the Sacred Heart. Kellogg, ID: Progressive Printing & Supplies, 1930.

Coeur d’Alene’s Old Mission State Park Visitors Guide. Cataldo, ID: Old Mission State Park, n.d.

De Smet, Pierre-Jean. Letters and Sketches, with a narrative of a year’s residence among the Indian tribes. Philadelphia: M. Fithian, 1843.

De Smet, Pierre-Jean. Oregon Missions and Travels over the Rocky Mountains in 1845–46. New York: Edward Dunigan, 1847.

Eberlein, Jake A. “Wilderness Cathedral: A History of the Coeur d’Alene’s Old Sacred Heart Mission at Cataldo, Idaho, 1846–1976.” Master's thesis, University of Nebraska at Kearney, 2014.

Evans, Lucylle H. Good Samaritan of the Northwest: Anthony Ravalli, S.J., 1812–1884. Missoula: University of Montana Publications in History; Stevensville: Montana Creative Consultants, 1981.

Fielder, George, and Roderick Sprague, Test Excavations at the Coeur d'Alene Mission of the Sacred Heart, Cataldo, Idaho, 1973. University of Idaho Anthropological Series, no. 13. Moscow, ID, 1974.

Gowans, Alan. “The Mission of the Sacred Heart.” Idaho Heritage 1, no. 3 (Winter 1976): 24-25.

Hart, Arthur A. “Architectural Styles in Idaho: A Rich Harvest.” Idaho Yesterdays 16, no. 4 (Winter 1972-1973): 2-9.

Hart, Arthur A., “Fur Trade Posts and Early Missions.” In Vol. 1, Space, Style and Structure: Building in Northwest America. Edited by Thomas Vaughn and Virginia Guest Ferriday. Portland, OR: Oregon Historical Society, 1974: 30-43.

Neil, J. Meredith. Saints and Oddfellows: A Bicentennial Sampler of Idaho Architecture. Boise, ID: Boise Gallery of Art Association, 1976.

McNeel, Jack. Union of Native American and Christian Beliefs Documented in Exhibit. Indian Country Today. October 24, 2011.

Peterson, Jacqueline, and Laura L. Peers. Sacred Encounters: Father De Smet and the Indians of the Rocky Mountain West. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993.

Point, Nicholas. Wilderness Kingdom: Indian Life in the Rocky Mountains, 1840–1847. Translated by Joseph P. Donnelly, SJ. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1967.

Robinson, Willard B. “Frontier Architecture: Father Ravalli and the Design of Coeur d’Alene Mission of the Sacred Heart.” Idaho Yesterdays 3, no. 4: (Winter 1959-60): 2-6.

“The Sacred Heart Mission, Cataldo, Kootenai County, ID.” Survey (photographs, measured drawings, written historical and descriptive data), Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1964.

Schroer, Blanche Higgins, W. C. Everhart, and Charles W. Snell, “Cataldo Mission/Coeur d’Alene Mission of the Sacred Heart,” Kootenai County, Idaho. National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form, 1963, 1976, 1983. National Park Service, U. S. Department of the Interior, Washington, DC.

Tuohy, Donald R. “Horseshoes and Handstones: The Meeting of History and Prehistory at the Old Mission of the Sacred Heart.” Idaho Yesterdays 2, no. 2 (Spring, 1958): 20-27.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.