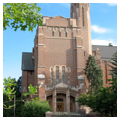

Memorial Gymnasium was built as a “living” memorial: it commemorated World War I soldiers while also providing a much-needed gymnasium for the University of Idaho campus.When first constructed, the five-story building was the largest university building in Idaho. With its wide Tudor arches, buttressed towers, elongated stained glass windows, and gargoyle-like figures, Memorial Gymnasium is one of the finest examples of Collegiate Gothic architecture in the state.

The United States’ participation in World War I transformed the University of Idaho. When most upperclassmen and some junior faculty left to serve in the armed forces, nearly 700 members of the Students Army Training Corps took their place, transforming the campus into a military camp. The need for increased food production led to an expansion of agricultural extension work and a change in the academic calendar to allow remaining students to harvest crops before starting the fall semester. Following the November 1918 armistice, the university honored the thirty-two students who lost their lives in the war with a memorial service and by planting a grove of thirty-two trees near the Administration Building.

Prior to the construction of Memorial Gymnasium, a smaller 1904 building served as the university gymnasium and armory. When, in March 1923, 1,500 fans squeezed into a space designed for 750 to watch the Idaho basketball team win its second Pacific Coast championship in a row, the overcrowding demonstrated the need for a larger facility. By April of that year, President Upham and Coach Matthews were already promoting a living memorial in the form of a new gymnasium to Moscow alumni and faculty. With no state funding forthcoming, faculty and alumni proposed raising $200,000 from university friends while students agreed to collectively contribute $15,000. Paul Davis, Commander of the Idaho Department of the American Legion, met with Upham, Alumni Association President W. B. Kjosness, and others to form the Idaho War Memorial Association, incorporated in June 1924. Despite concerted fundraising efforts only $70,000 had been raised by 1926 and the association had to develop a creative fundraising scheme: issuing bonds, with annual rent from the regents to pay off the bonds and interest, after which the university would own the building.

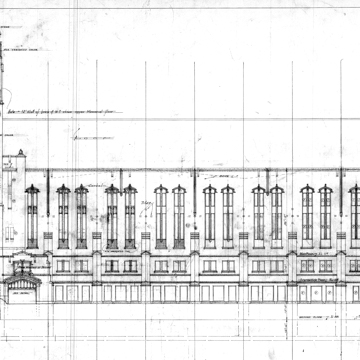

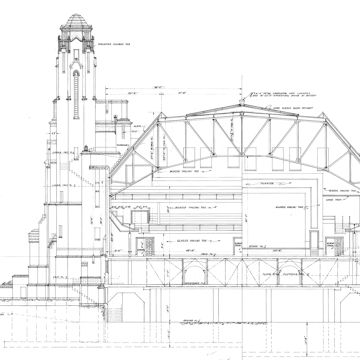

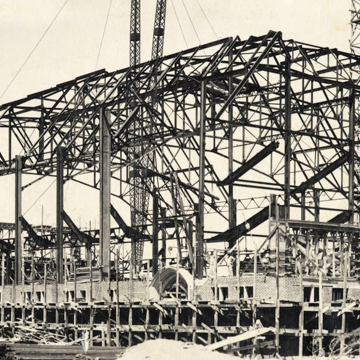

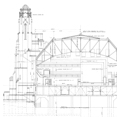

Rudolph Weaver, University Architect and Head of the fledgling Department of Architecture, began plans for the memorial gym but he left Idaho in 1925, so it is not clear how much he contributed to the design. David C. Lange replaced Weaver as both University Architect and Head of the Department of Architecture. Thus, Lange was the Architect of Record for the memorial gym. Assisting him was Theodore Prichard, who went on to lead the architecture department for almost forty years. The memorial gym was bid in July 1927, but the lowest bid came in $70,000 higher than the $300,000 available for construction. To reduce costs, President Upham and the Memorial Association decided to build the gymnasium without its west end, initially planned to contain a stage, stair towers, and several elaborate Gothic entrances. Construction commenced that year and by November 1928, the building was substantially complete and the Idaho War Memorial Association officially presented the building to the University. Construction was completed in 1929 and an eight-foot-long bronze tablet with the names of all “Sons of Idaho who made the Supreme Sacrifice in the World War 1914–1918” was installed in the lobby.

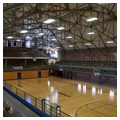

The five-story, 90,000-square-foot, rectangular gym was built in the southwest quadrant of the University of Idaho campus. Within the three-story basketball arena, construction—including exposed steel trusses, steel columns, and structural clay tile walls—is revealed. The exterior, on the other hand, is a dramatic and eclectic incarnation of the Collegiate Gothic style whose appearance seeks to create an effect rather than reveal its making. Yet stepped buttresses do define structural bays and reveal the location of steel inside as stringcourses define floor levels. Within each structural bay are two pairs of tall, slender windows that span most of the height of the three-story arena. Below each pair of windows, but above a cast stone sill, is a panel of multicolor, square, glazed tiles. Then comes the most curious feature: separating the windows in each pair, is a crouched football player supporting a colonette upon which sits a chimera peering down to the football player, all in cast stone. A single Tudor arch of splayed bricks spans each pair of windows and splayed bricks form the jambs. Windows and buttresses march rhythmically along the north facade toward the buttressed square tower at the northeast corner. A monumental staircase leads to the base of the tower where a single, broad, Tudor arch spans the tripartite entrance. Above the entrance is a cluster of four tall, slender, stained glass windows. Near the top of the tower is a frieze of four cast stone bas relief panels depicting a cowboy, an Indian, a miner, and a frontiersman. Immediately to the west of the square tower is a taller and more slender domed octagonal tower, the pinnacle of the building.

Three of the figures in the bas relief frieze represent Idaho’s historic economies—trapping, mining, and ranching, but the fourth is a stereotypical “Indian” who holds a tomahawk and who does not represent local Indigenous people such as the Nez Perces and Coeur d’Alenes; even more problematically, he is the target of the adjacent cowboy figure’s gun. As such, the relief offends Indigenous people, some of whom participate in the annual Tutxinmepu Powwow that was held for many years in Memorial Gymnasium. Although the bas relief is offensive, Indigenous communities honor veterans and respect war memorials, thus the building’s meaning is complicated for Indigenous people.

Inside the building, the august lobby serves as a traditional memorial. A cast-stone, Tudor arch frames each side of the vertical, square hall, and a ribbed vault forms the ceiling. Stained glass windows along the north and east admit light that falls on flags mounted on south and west walls. A monumental stair ascends to an alcove along the south with the bronze tablet commemorating World War I soldiers, now crowded by additional plaques commemorating wars from the last century. In contrast with the lobby, no traces of Gothic architecture can be found in the arena; it is all about basketball, with a maple floor large enough to accommodate three practice courts, three tiers of seating to accommodate spectators at tournaments, and naked steel trusses above.

In 1952, a thirty-foot-wide addition designed by Victor N. Jones was built on the west end, similar in footprint to the portion of the building not completed in 1929. The four-story addition included a stage and restrooms at the main level and coaches’ offices and a varsity locker room below. New folding bleachers on the west end increased the seating capacity to 5,000. Critical to circulation of the whole building, the addition contained a stair tower and entrance at each corner. Although the addition employed red brick for the walls, it is austerely modern in style. There are no Tudor arches in sight, but rather, squarish windows, glass block, and entrances marked by horizontal, planar concrete canopies.

In addition to being the hub of athletic activity at the university, Memorial Gym served a variety of other purposes as it was the largest gathering space on campus until the Kibbie Activity Center was completed in 1976. Memorial Gym was the place for commencement, concerts by musicians such as Leontyne Price and Dave Brubeck, and all of the campus’s largest and most significant events between 1929 and 1976.

After athletic events moved into the Kibbie Center, Memorial Gym underwent an extensive interior renovation that was completed in the early 1980s at a cost of $1.2 million. Ramps and an elevator were installed and doorways were modified to make the building more accessible. A new maple gym floor replaced the older one. The entire locker floor, the level beneath the gym floor, was modernized. Since then, other renovations have included the 2009–2010 repairs to the exterior masonry and the 2012 structural upgrade to the octagonal tower.

Memorial Gymnasium continues to accommodate a multitude of competitive athletic events, physical education classes, and organizations such as the Women’s Center and ROTC. And regardless of use, Memorial Gymnasium continues to serve as a war memorial, not only for those who gave their lives in World War I, but for soldiers from more recent wars too, as the cluster of bronze plaques in the lobby attest. As one of the finest Collegiate Gothic buildings in the state, Memorial Gymnasium is one of the most significant buildings on the University of Idaho campus. It serves as a landmark at the southern terminus of one of the major walkways of the Olmsted-designed campus of Idaho’s flagship land grant university.

References

Gibbs, Rafe. Beacon for Mountain and Plain: Story of the University of Idaho. Moscow: University of Idaho, 1962.

Hibbard, Don. “Memorial Gymnasium,” Latah County, Idaho. National Register of Historic places Inventory-Nomination Form, 1977. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, DC.

“Idaho Gym Bids Are Too High.” Spokesman-Review, July 17, 1927.

“Idaho Memorial Gym Plans Ready: University Building Costing $250,000 May Be Erected This Autumn.” Spokane Daily Chronicle, July 9, 1926.

“Idaho Team Has Five Veterans: Basketball Squad Starts Practice in New Memorial Gym—New Material Promising.” Spokesman-Review, December 2, 1928.

“Idaho to Build Memorial Gym: Alumni Leaders and Faculty to Present Plans for $200,000 Structure in June.” Spokesman-Review, April 28, 1923.

“Idaho U Plans Memorial Gym.” Spokane Daily Chronicle, August 20, 1923.

“Indorses Memorial Gym.” Spokesman-Review, April 25, 1924.

McDonald, George, and Edward Coon, ed. The Gem of the Mountains. Moscow: University of Idaho, 1929.

“Memorial Gymnasium, 1927-.” The University of Idaho Library's Campus Photograph Collection. Accessed June 6, 2015. http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/digital/campus/locations/MemorialGymnasium.html

“Memorial Gym Addition Gives Idaho Expanded Athletic Plant.” Lewiston Morning Tribune, August 11, 1952.

“Muscovite Gym Ready for Use.” Deseret News, August 11, 1952.

Otness, Lillian Woodworth. A Great, Good Country: A Guide to Historic Moscow and Latah County, Idaho. Moscow, ID: Latah County Historical Society, 1983.

Petersen, Keith. This Crested Hill: An Illustrated History of the University of Idaho. Moscow: University of Idaho Press, 1987.

Reese, D. Nels. “Tribute to Memorial Gymnasium.” Address delivered on November 11, 2010.

Turner, Alexiss. “Memorial Gym: 1928-present.” Then & Now: History Across the University of Idaho Campus. University of Idaho Vandal Vibe Newsletter. Accessed June 6, 2015. http://www.uidaho.edu/alumni/stay-connected/vibe/features/memorial-gym

“Vandals Hope for Victory in Memorial Gym Finale.” Spokane Daily Chronicle, March 1, 1975.