In 1880, railroad magnate George M. Pullman founded an industrial town on undeveloped prairie south of downtown Chicago. The Town of Pullman eventually included factories, community buildings, and 1,700 residences. Pullman believed that a pleasant environment would have an uplifting effect on its inhabitants, and that a well-designed factory town would foster stability and happiness in its workforce. A crucial corollary was that the worker happiness produced by the town’s serene environment would forestall unionization and produce a six percent annual return on investment, thus serving as a model for other “enlightened” industrialists. Pullman’s town did become an inspiration, but to workers, not owners, as it became an emblem of the power of unified labor. Though it is now diminished in size, the Town of Pullman remains a visually cohesive community that tells an important story about labor, factory production, and American rail travel at the turn of the twentieth century.

In 1864, Pullman began manufacturing rail cars with private compartments that converted from seats to fold-down bunks at night. Before long, Pullman’s name became synonymous with the luxurious cars he produced in his first factories in Detroit. With his business a great success by 1879, Pullman decided to build a new, purpose-built facility for his Pullman Palace Car Company. He purchased 4,000 acres of vacant low-lying land in Chicago, fourteen miles south of the Loop. The site was advantageously located on a long, narrow plot bordered by Lake Calumet on the east and the Illinois Central Railroad to the west. But because of its remoteness, the site required Pullman to provide housing for his employees. This led him to conceive a community far more comprehensive and substantial than factory towns elsewhere in the United States at the time, a community that would, as a result, reinforce his company’s reputation for beauty, order, and efficiency.

Central to Pullman’s ambitions was that his new town should contain distinct the industrial and residential sections, but this idea was not unprecedented. The masonry tenement buildings and reform school at the Scottish cotton mill town of New Lanark were nearly a century old in 1879, and Pullman may have visited the well-planned woolen mill village of Saltaire (1851) on a trip to England. Closer to home, beginning in the 1820s, the Lowell Company in Massachusetts housed its young female employees in a planned town of chaperoned boardinghouses. In fact, factories throughout the United States provided residences for their workers—either through direct building or incentivized independent construction—but Pullman’s scope and ambition distinguished his effort. To help him realize this scheme he hired landscape architect Nathan Barrett, who had laid out his New Jersey estate, and architect Solon Beman, then a young New York architect just two years out of Richard Upjohn’s office. They began design work in December 1879. Construction started in May 1880 and the first residents moved into town on New Year’s Day 1881. In a ceremony held in April of that year, Pullman’s eldest daughter, Florence, started the factory’s massive Corliss engine, inaugurating the entire plant. By summer 1883, the town’s civic and institutional buildings were completed, although housing construction continued for another seven years. By July 1888, Pullman’s population had grown to 10,560.

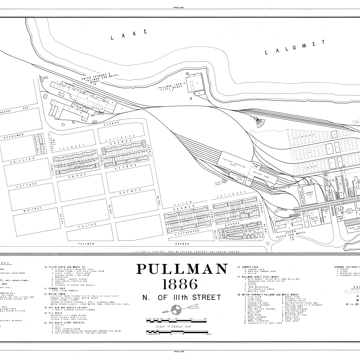

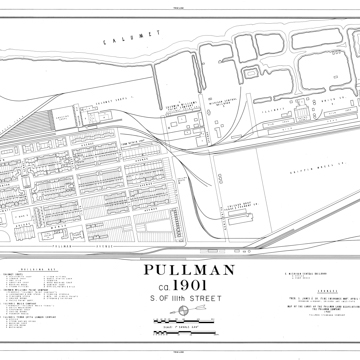

Barrett imposed a regular street grid on the area, and divided it into three sections, each occupying the full east/west width of the site, with a small residential district to the north (103rd to 108th streets), the factories in the center (108th to 111th streets), and the more significant residential and commercial district to the south (111th to 115th streets). Athletic Island occupied the marshes between the southern residential section and Lake Calumet to the east. A rail spur ran to the east and Pullman Avenue paralleled the Illinois Central to the west. The Illinois Central stop at 111th Street, the boundary between the factory and southern residential district, formed the center of the community.

Just north of the Illinois Central stop at the northeastern corner of 111th and Pullman Avenue, Beman designed the impressive, red brick Administration Building (1880), whose central clock tower announced the structure’s importance as the heart of the factory. The Administration Building once stood along the shore of the manmade Lake Vista, as the centerpiece of a park featuring a waterfall, bandstand, and walking and driving paths—a pastoral welcome to the industrial facility. One-story brick shops were attached on the north and south sides of the Administration Building. To the east, behind the Administration Building, the spur line connected the many factory buildings, which, typically, were sturdily constructed of brick with steel-trussed roofs. In addition to the Pullman Car Works, the Union Foundry, and the Allen Paper Car Wheel Works, many other industries were located on site. An early and advanced example of vertical integration, the Pullman facility produced nearly all the materials required for the manufacture of its rail cars, purchasing only glass, carpet, and fabric. For decades the largest manufacturer of rolling stock in the United States, Pullman produced 600 sleeping cars and 7,000 freight cars a year, prior to 1894.

The southern residential section developed before the smaller residential area to the north, and contained Pullman’s public and commercial spaces. South of the rail station and the Administration Building, a large, landscaped square welcomed visitors. The Hotel Florence, which opened on November 1, 1881, stands at the northeast corner of the block, and hosted railroad executives arriving in town to conduct business. The Arcade Building, opened in May 1882 (demolished 1927), occupied the southern end of the square, and contained a theater, library, offices, meeting rooms, a bank, and stores. The substantial two-story, red brick building had a high rough-cut limestone base and three-story central pavilion, lending an eclectic French Renaissance tone to the largely Romanesque Revival and Queen Anne Style buildings throughout the rest of the town.

Beman also designed a fire house, stables, a casino, and an English Gothic Revival school, which all lay south of the Arcade Building on the east side of Pullman Avenue. The arched brick stables with diamond-cut wood siding on the second floor were designed in the developing Shingle Style. South of the Arcade Building, across 112th Street, Beman designed the Richardsonian Romanesque Greenstone Church (1882), meant to serve as the spiritual center of the town. Initially intended for the use of all Christian denominations, Pullman’s rents on the building proved too high for many congregations, who sought lower cost meeting places elsewhere.

One block east of the Greenstone Church, the Market Hall is located in a square at the intersection of 112th Street and South Champlain Avenue. The original two-story, red brick Market Hall opened in March 1882 but burned down a decade later. Beman then redesigned the square to make it a more unified composition; curving, two-story row houses with first-floor arcades define the edges of the square, with the three-story, red brick and limestone-arched Market Hall.

Pullman himself lived in a Second Empire mansion on Prairie Avenue, ten miles north of the factory, but large Queen Anne houses for railway executives line the south side of 111th Street, facing the factory. South of these, worker’s houses occupy the area south to 115th Street, designed with the same vocabulary of brick, limestone, and wood shingles. Built to accommodate varying family sizes and rent levels, some units are individual or paired row houses, while apartment buildings and boarding houses accommodated small families and single workers. Most are two stories tall, and there is little standardization of plan or elevation. The houses just south of Market Square are most similar to the main public buildings, while south of 113th Street, and in the residential district north of the factory, buildings are simpler, brown brick structures with less stone detailing. All units had running water, a toilet, and gas—generous amenities for worker housing at the time.

Pullman’s thoroughness extended to the town’s infrastructure. Dredging clay from Lake Calumet improved draft in the lake, while also supplying clay for a brickworks, which not only produced most of the bricks for the town’s residences but also produced brick for sale. A massive, twenty-story water tower (demolished 1957) northeast of the Administration Building stored 500,000 gallons of Lake Michigan water for fire suppression and also served the town’s separated sewage system, which delivered rainwater from Lake Calumet and piped it to a farm three miles south, where much of the produce for sale at Market Hall was grown.

Pullman may have viewed his factory town as a physical and social ideal, but he expected a generous rate of return on his investment, not only in the form of profit but also in a stable, non-unionized workforce. From the workers’ perspective, the clean streets, new buildings, services, and amenities were obviously preferable to the deteriorated housing available elsewhere, but there were distinct disadvantages. Pullman rented the houses with no option to buy them, so workers were never able to build equity. The company deducted rents directly from paychecks, and many workers believed that managers favored those who lived in Pullman over those who lived outside of town. In addition, rents were so high that many families were forced to take in boarders. Overall, Pullman’s thoroughness created a highly controlled community. To discourage excess drinking among his workers, Pullman banned alcohol in town (except for middle- and upper-class guests at the Hotel Florence). As he well understood, this meant also eliminating taverns, which were workers’ traditional locales for socializing and unionizing. He also banned the production of a local newspaper, denying residents a communal voice, and the company had a strict code of conduct that many workers felt impinged on their personal lives.

During the Panic of 1893, Pullman cut his workers’ wages but did not lower their rents or utility costs, an act that transformed him from a benefactor to a profiteer in the eyes of many of his employees. This new dissatisfaction merged with long-standing resentments to produce an effective unionization drive. Workers joined the American Railway Union, led by Eugene V. Debs. They demanded lower rents in light of their reduced wages but Pullman refused to negotiate. Workers began striking on May 11, 1894. On June 26, Debs called for all union members to boycott trains with Pullman cars, and within four days, 125,000 workers on 29 railroads walked off the job, causing a near-total shutdown of the nation’s rail system, including federal mail delivery. President Cleveland sent the National Guard to Chicago, and the first strikers were shot on July 8. By the end of July, 34 workers were dead. A subsequent presidential commission laid much of the blame on Pullman, citing the town’s paternalist structure and his unwillingness to negotiate.

Pullman died in 1897, and the next year the State of Illinois forced the company to sell all of its non-industrial lands. In 1899, Lake Vista was filled in as the city extended Cottage Grove Avenue close to the Administration Building. Train yard expansion eliminated Athletic Island to the east of town. Pullman residences were sold in 1907 and have been privately owned ever since. In the 1920s, diversification, including Packard automobile production, made up for a decline in railcar demand, but production halted during the deepest years of the Great Depression. During World War II, the factory produced airplane wings and converted railcars into troop trains, but the railcar market continued its decline in postwar years. The company consolidated production in a modern factory on site, and the other manufacturing buildings were demolished or sold. In the 1970s, Amtrak and subway orders brought new activity to the factory, but railcar production finally ceased at Pullman in 1982.

The Pullman Historic District achieved national, state, and city landmark designations in the 1970s, preventing demolition of several of the public buildings. In 1991, the State of Illinois acquired the site for a transportation museum, but a fire in 1998 undermined that effort. The buildings were stabilized in 2005, but with only a few exceptions have largely remained vacant. The Greenstone Church has had a continuously active congregation since it opened in the 1880s. The Illinois Historic Preservation Agency now runs the Hotel Florence as an event venue. The stable survives as an auto repair shop, but the ground floor of the Market Hall is a ruin. The Town of Pullman was declared a National Monument in 2015, stirring new hope for the revitalization of the vacant buildings, many of which retain their architectural integrity.

References

Crawford, Margaret. Building the Workingman’s Paradise: the Design of American Company Towns. London: Verso, 1995.

Dinus, Oliver J., and Angela Vergara. Company Towns in the Americas. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

Jackson, Donald, and Carol Poh Miller, “Pullman Industrial Complex,” Cook County, Illinois. Historic American Engineering Record, 1976. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Lillibridge, Robert M., “Pullman: Town Development in the Era of Eclecticism,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 12, no. 3 (October 1953): 17-22.

Lindsey, Almont. The Pullman Strike: The Story of a Unique Experiment and of a Great Labor Upheaval. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1942.

Snell, Charles, “Pullman Historic District,” Cook County, Illinois. National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 1970. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.