You are here

San Esteban

Acoma’s San Esteban is the most intact seventeenth-century Spanish Colonial mission in New Mexico, made more memorable by its dramatic location and the austere planes of its cliff-like walls. A product of continued maintenance and significant restorations, it was also marked as an iconic example of the Spanish-Pueblo Style by the restoration work of architect John Gaw Meem.

Fray Jéronimo de Zárate Salméron claimed to have been the first missionary priest to work among the Acoma in 1623–1626. He was followed by Fray Juan Ramírez, who directed the construction of San Esteban in 1629–1644. Built over the ruins of the sixteenth-century pueblo on the south side of the mesa, it symbolized Spanish dominance at a time when the destruction of the original pueblo by soldiers under Juan de Oñate in 1599 was still a living memory. The church’s east-west axis parallels the pueblo, but the distance between them—which was more emphatic before later construction filled the intervening space—speaks of the ideological differences between Spanish missionaries hostile to native beliefs and a Native people wary of missionization. During the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, Acoma killed the resident friar but chose not to burn the mission, which was intact except for some broken windows when Diego de Vargas visited in 1692 during his reconquest of New Mexico. Franciscan friars returned in 1699, remaining until 1782 when San Esteban became a visita of the mission at Laguna Pueblo, where the priest was moved. Left in Acoma’s care, San Esteban is now visited by a priest of the Gallup diocese only on special feast days.

The mission comprises a large, single-nave church, an attached residence or convento to the south, and a cemetery or camposanto extending east from the church facade to a massive retaining wall at the mesa’s edge. Derived from sixteenth-century mendicant establishments in central Mexico, the missions of seventeenth-century New Mexico adapted the scale, proportions, and plans of those vaulted stone structures to constructions of adobe and timber that both fit with the indigenous building traditions and imported practices from southern Spain.

The church is 145 feet long, 44 feet wide, and 32 feet high, with massive walls of stone veneer over adobe brick. Between two projecting corner towers, the simple planar facade is broken only by a choir window over heavy wooden doors. The nave has a choir loft over the entrance and a raised polygonal sanctuary without transepts at its west end. Originally, doors beneath the choir loft led left to a baptistery and right to the convento. Now lit by two windows in the south wall, the impressive interior rises some fifty feet to what initially were massive squared vigas 40 feet long; resting on corbels set into the nave walls, these supported layers of latillas, yucca leaf mats, and packed adobe. All of the construction materials—adobe, stone, and timber—were brought up to the mesa top from below. According to oral histories, the beams were carried from Mount Taylor 30 miles away. The original corbels remain, but round vigas and modern roofing have replaced the earlier roof. Frequently renewed mural paintings in the nave have featured Pueblo imagery of clouds, plants, animals, rainbows, and water jars.

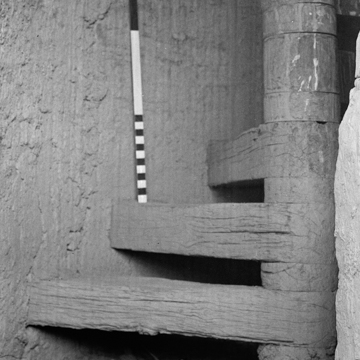

Acoma’s convento (closed to the public) is a rare extant example of a mission residency in New Mexico. Entered through a porteria, or vestibule porch, in its southwest corner, the one-story structure rises to a second-story on its north side with a mirador, or roofed balcony, at its northwest corner. Enclosed ambulatories and rooms surround a large square patio, roughly 66 feet on a side, with living quarters and workspace that included rooms for receiving visitors, sleeping, storage, labor, and dining. The walls probably date to the seventeenth century, though the convento has been frequently reroofed with recycled materials. Some vigas date to about 1700, while reused latillas show paint from earlier ceilings. In 1976, traces of mural paintings in earth pigments on white plaster were uncovered in the ambulatory, including rainbows, terraced clouds, mounted horsemen, and animals.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the mission had become a weathered ruin, the roofs leaked badly, the exposed south wall of the church sloughed off layers of structural stone and adobe, and the tops of the facade towers eroded to mere stalagmites. A partial restoration between 1902 and 1911 erected new belfries on the towers. Then, from 1925 to 1929, John Gaw Meem and the Society for the Preservation of New Mexico Mission Churches worked with Acoma under the supervision of Lewis Riley and B.A. Reuter to carry out a major restoration of San Esteban. Blending preservation science with artistic speculation, Meem’s restoration both stabilized the badly degraded structure and made formal adjustments to recreate what he thought was its most “authentic” state. The nave roof and the facade towers were rebuilt, while the nave walls—especially on the south side—were extensively repaired, with new parapets, canales, foundations, and facing. This reconstruction gave Meem the opportunity to refine the battered massing and majestic profiles of San Esteban and replace the boxy early twentieth-century belfries with gently tapered ones deemed more suited to the newly restored “ancient model.”

In an interesting case of revisionism, Meem’s restoration fit the historical (if mutable) fabric of San Esteban to aesthetic expectations shaped by the Spanish-Pueblo Style. First given a coherent and permanent expression in Rapp, Rapp, and Hendrickson’s New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe (1915–1917), which adopted the Acoma mission as one of its models, this style was then codified by Meem in the 1930s in a series of works including Scholes Hall at the University of New Mexico (1934–1936), which reciprocally was based on the restored mission. In between, the historical model of San Esteban had been adjusted to look like its copies, rather than the reverse.

The camposanto’s retaining wall and the convento were rebuilt and restored in 1974–1975; further repairs to the church roof were made after 1980. These and other restoration projects have preserved while continuously remaking the mission structure. Justifying the seemingly contradictory and equally truthful claims that San Esteban is at once the best-preserved seventeenth-century mission church in New Mexico, and almost entirely rebuilt, this paradox suggests that a mutable persistence over time is one of San Estaban’s defining characteristics. Monumental adobe architecture depends upon a community engaged in its maintenance, and the strong bonds that Acomas express towards their mission through active upkeep are essential to its survival, signifying commitment to a site of collective memory and a physical link between generations.

References

Bergman, Edna Heatherington. Historic Structures Report Mission San Esteban Rey Pueblo of Acoma, New Mexico. 1980. Prepared by Chanell Graham Architecture/Pacheco & Graham Architects, SR 23, New Mexico Historic Preservation Division, Santa Fe, NM.

Dominguez, Fray Franciscao Atanasio. The Missions of New Mexico. Translated and annotated by Eleanor B. Adams and Fray Angélico Chávez. Santa Fe: Sunstone Press, 2012.

Kessell, John L. The Missions of New Mexico Since 1776.Santa Fe: Sunstone Press, 2012.

Kubler, George. The Religious Architecture of New Mexico: In the Colonial Period and Since the American Occupation. 4th ed. Albuquerque: School of American Research and University of New Mexico Press, 1973.

Marshall, Michael P. “Investigations at the Mission of San Esteban Rey, Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico: A Preliminary Report.” 1978, SR 23, New Mexico Historic Preservation Department, Santa Fe, NM, 28.

Mauldin, Barbara B. The Wall Paintings of San Esteban Mission, Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico: A Description and Analysis. Master’s thesis: University of New Mexico, 1989.

Minge, Ward Alan. Acoma: Pueblo in the Sky. Rev. ed. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2002.

Playdon, Dennis G., and Brian D. Vallo. “Restoring Acoma: The Pueblo Revitalization Project.” Cultural Resource Management 23, no. 9 (2000): 20-24.

Scully, Vincent. Pueblo/Mountain, Village, Dance.New York: Viking Press, 1972.

Treib, Marc. Sanctuaries of Spanish New Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Wingert-Playdon, Kate. John Gaw Meem at Acoma: The Restoration of San Esteban del Rey Mission. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2012.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.