You are here

Blackwater Draw National Historic Landmark

Blackwater Draw is a significant site of early human occupation in New Mexico, where traces of camping and hunting around an ancient basin became the focus of twentieth-century archaeological excavations, as industrial gravel quarrying exposed artifacts crucial to understanding early Americans known as Paleoindians. The site’s complex history and its importance in developing archaeological models of the past led to its recognition as a National Historic Landmark. Today, Eastern New Mexico University (ENMU) administers its 157 acres as a landscape for research and public interpretation.

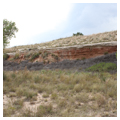

Blackwater Draw is a dry valley amidst the semi-arid grasslands of the Llano Estacado plateau, between the Canadian and Pecos rivers. It stretches from Portales and Clovis, New Mexico, to Lubbock, Texas. It once was relatively moist and flowed with water in the late Pleistocene (roughly 20,000-10,000 years ago). A shallow basin and spring-fed pond sat north of the main channel, attracting diverse megafauna such as mammoths, bison, horses, camels, bears, and dire wolves, as well as Paleoindian hunters beginning around 11,400 years ago. As sediments accumulated and the climate changed, springs ceased and the stagnant pond became a shallow marsh before drying up completely. Its gradual aggradation and sustained human occupation produced a robust stratigraphy and the most-complete sequence of Paleoindian artifacts in the southern plains.

People of the Clovis culture first used the site approximately 11,400 to 10,800 years ago, killing game around the lake and camping on high ground. They were mobile hunters and gatherers, whose distinctive lanceolate-shaped projectile points occur throughout North America. Using high quality stone from distant quarries, Clovis hunters formed large spear points with “flutes,” or concave flakes removed from their basal ends. Nine of the twenty-eight mammoths from the Blackwater Draw site have clear Clovis associations, but such kills may have been relatively infrequent events, with only a handful occurring per century at Blackwater Draw. Rather than relying upon mammoths, Clovis people probably practiced a diversified strategy of hunting and gathering.

In addition to projectile points, Clovis users of Blackwater Draw left behind a range of stone and bone artifacts, with buried caches of such materials as sharp prismatic blades for future use. Other finds included everyday domestic tools, probably from small household encampments on the basin’s upper margins near springs and arroyos. Archaeologists believe the Clovis people lived in readily portable wood-frame structures covered in mats or hides, quickly erected and leaving little archaeological evidence.

Across the Plains, Folsom culture succeeded Clovis circa 10,800 to 10,200 years ago. Mammoths were extinct, and Folsom people relied upon ancient bison, antelope, mountain sheep, and small game. Their points show technical continuities with Clovis, but are smaller and more refined with full-length fluting, as well as similar unfluted Midland points. Folsom artifacts are restricted to the Great Plains and adjacent mountains, where they doubled down on mobile hunting as a subsistence strategy, sometimes taking advantage of such natural features as arroyos to trap and kill herds of bison. In one kill site at Blackwater Draw, hunters appear to have mired bison in mud, killing and butchering them in place.

Folsom people continued the Clovis pattern of camping along the margins of the basin. One site known as the Mitchell Locality has yielded thousands of scattered stone flakes that indicate distinct areas for such activities as flintworking and hide processing. Folsom tools included scrapers, gravers, and large, thin bifaces that were highly crafted and lightweight.

The Folsom period climate in the southern plains was similar to that of the Clovis era, but began drying by 10,200 years ago, with drought leading to declining use of the Llano Estacado. Streams dried and the basin became a muddy marsh that accumulated wind-blown sediment. Though Late Paleoindian occupations remain poorly understood at Blackwater Draw, a number of well-made, unfluted projectile point types appearing until around 8,500 to 8,000 years ago indicate that hunting continued. Subsequently, Native peoples from the Archaic period left behind triangular, stemmed points and occasional bison kills, but their strongest markers are hand-dug wells in the sediment-choked basin. Clovis people probably made the first well, but the practice was more important to Archaic users who dug shafts four to six feet deep in the dry basin surface, roughly 6,500 to 4,000 years ago.

Blackwater Draw’s ancient history came to light as dustbowl winds removed surface soils to expose earlier strata, and the construction of new roads and nearby Cannon Air Base created a demand for gravel. In 1932, the archaeologist Edgar B. Howard heard of Paleoindian artifacts in the area, just as the New Mexico Highway Department began mining gravel at the Blackwater Draw site, uncovering mammoth bones in the process. Howard conducted excavations from 1933 to 1937, uncovering extinct fauna directly associated with Paleoindian artifacts.

Howard’s excavations were notable for their interdisciplinary nature, comprising one of the most comprehensive research programs of the time. His finds spoke directly to the most pressing questions of North American anthropology in the 1930s, when the origins of Native American peoples were hotly contested. Some believed that Indians had arrived only a few thousand years ago, but the coexistence of delicate projectile points and extinct bison at the Folsom site in Union County, New Mexico, laid this dispute to rest in 1927. Howard’s fluted projectile points with mammoth bones pushed back further the date of Paleoindian arrival, and E. H. Sellards’ 1952 description of Blackwater Draw made it the type site for Clovis culture. Early work at the site contributed, however, to inaccurate perceptions of Paleoindians as strictly big game hunters, and to the “Clovis First” paradigm of American origins. The discovery of pre-Clovis archaeological sites and evidence of a more complex process of peopling have now overturned this paradigm that Paleoindians first arrived around 13,500 years ago by following herds across a land bridge between Siberia and Alaska.

Until 1952, gravel mining at Blackwater Draw remained relatively low intensity, while there was little excavation except by Sellards and Glen Evans for the Texas Memorial Museum. The subsequent history is more complex, involving numerous scholars, institutions, and local collectors. In 1952, the site was leased to Sam Sanders for industrial gravel mining, initiating a chaotic phase of salvage archaeology, as numerous excavators and institutions vied for access. It was also a period of spectacular finds, such as the El Llano Archaeological Society excavations of five mammoths beginning in 1962. This discovery motivated the first serious attempts to preserve the site, and its initial listing as a National Historic Landmark. Sanders eventually rejected a purchase offer from the state legislature, and moved to reduce the chaotic conditions at Blackwater Draw by giving ENMU exclusive archaeological access.

By the 1970s, gravel mining had ended, leaving behind two large pits cutting through the original basin. The site became a haunt of amateur collectors, off-road vehicle enthusiasts, and target shooters; ENMU continued to run field schools until 1974, when the pits were deemed unsafe. In 1978, ENMU worked with state and federal governments to buy the site for preservation and archaeological investigation, and in 1991 Blackwater Draw opened to the public. Subsequent research initiatives have included new excavations along the southern embankment (1983–1984) and the Mitchell locality (1985–1986).

ENMU has restructured Blackwater Draw as an educational landscape, with walking paths, signage, and a South Bank Interpretive Center (1994–1998), which protects displays of ancient strata and Paleoindian kill sites in situ. Recent work has concentrated on analyzing faunal remains from prior excavations; locating and recovering dispersed artifacts; synthesizing previously unpublished excavation data; reassessing and in some cases re-excavating earlier finds; and evaluating previously collected specimens.

As a result of its complicated intermeshing of modern and ancient landscapes, the Blackwater Draw site has become a valuable cultural resource for constructing archeological narratives of the ancient past. It remains one of the most important locales for Paleoindian research in North America, with efforts ongoing to make sense of its chaotic excavation history and generate new data. While mining may have destroyed as much as 90 percent of the original site, it is likely that many artifacts remain in place for future research. Gradual recognition of the complexity of North America’s peopling has lent renewed urgency to rethinking Paleoindian history and primary sources such as Blackwater Draw.

The Blackwater Draw Site is open seasonally. The museum is open year round for self-guided tours.

References

Bennett, Stacey D. Blackwater Locality 1: Synthesis of South Bank Archaeology, 1933-2013. Master’s thesis, Eastern New Mexico University, 2014.

Boldurian, Anthony T., and John L. Cotter. Clovis Revisited: New Perspectives on Paleoindian Adaptations from Blackwater Draw, New Mexico. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum, 1999.

Graf, Kelley E., Caroline V. Ketron, and Michael R. Waters, eds. Paleoamerican Odyssey. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2014.

Hester, James J., with Ernest L. Lundelius Jr. and Roald Fryxell. Blackwater Locality No. 1: A Stratified, Early Man Site in Eastern New Mexico. Ranchos de Taos, NM: Fort Burgwin Research Center, 1972.

Holliday, Vance T. Paleoindian Geoarchaeology of the Southern High Plains. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1997.

Katz, Lienke. The History of Blackwater Draw. Portales: Eastern New Mexico State University Printing Services, 1997.

“Memoir 24: Lithic Technology at the Mitchell Locality of Blackwater Draw: A Stratified Folsom Site in Eastern New Mexico.” Plains Anthropologist 34, no. 130 (September 1990).

Sellards, Elias H. Early Man in America: A Study in Prehistory. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1952.

Thomas, David Hurst. Places in Time: Exploring Native North America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.