You are here

Bosque Redondo Memorial

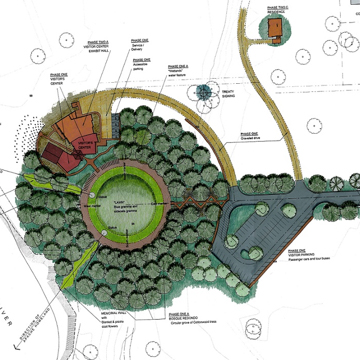

The Bosque Redondo Memorial at Fort Sumner State Monument commemorates the site where thousands of Mescalero Apache and Navajo people were imprisoned between 1862 and 1868. The journey to Bosque Redondo, now known as “The Long Walk,” and the subsequent hardships internment imposed were devastating. Of the 11,000 Navajo (Diné) who departed for Bosque Redondo beginning in 1864, only 6,800 returned in 1868. Bosque Redondo translates from the Spanish as “circular grove of trees.” This inspired architects David Sloan (Diné) and Johnpaul Jones (Cherokee-Choctaw) to design the memorial as a ring of cottonwoods with a visitor center wedged into its northwest side. As designed, the arrangement of the trees would include two openings with sightlines toward the Mescalero and Diné homelands. The restoration of the Pecos River watershed along the western edge of the circle will offer an exemplary site for teaching the importance of conserving the land.

In 1862, Bosque Redondo was a military reservation covering 40 square miles along the Pecos River in the southeastern New Mexico Territory. As violence escalated between Euro-Americans and the Mescalero and Diné, Brigadier General James H. Carleton, commander of the Department of New Mexico, seized upon a plan that would remove both groups from contact with settlers and teach them to become sedentary farmers. After the tribes refused Carleton’s request to move to Bosque Redondo, he ordered the U.S. Army to compel them to go. The Mescalero started arriving in 1862 and the Diné, who traveled south along the Pecos River Valley, in 1864. By 1865, 500 Mescalero and 8,500 Diné were living at Bosque Redondo along with 400 soldiers. The entire Mescalero population departed under cover of night later that year, but most of the Diné, who were several hundred miles from their homeland, remained. Efforts to farm the land failed abysmally, and disease and malnutrition took an enormous toll. By 1868, the federal government agreed to sign a treaty that would allow the Diné to leave Bosque Redondo. The treaty formally established the Navajo Reservation and recognized the various Diné bands as a sovereign entity, now known as the Navajo Nation.

Architect Sloan, a Native American design professional, has worked on projects across the country, including the Smithsonian Institution’s Cultural Resource Center for the National Museum of the American Indian and the master plan for Haskell Indian Junior College. At Bosque Redondo, there were a number of reasons to consider a design rooted in the landscape. These included the setting of the historical internment, which was spread over many square miles, and the need for a place to experience the healing that nature can offer. Jones, the lead landscape architect for the National Museum of the American Indian, offered Sloan a concept for the memorial that fulfilled the complex requirements of the project.

The design connects the circle of cottonwoods to the main parking lot with an eastward entrance facing the dawn. John McMillan, former mayor of Fort Sumner and a key advocate for the memorial, had 100 seedlings cloned from an ancient cottonwood that dated to the internment at Bosque Redondo. These seedlings served as the foundation for the grove. The main path into the memorial passes through the trees to a circular path surrounding an area with plants that sustained the Native American way of life. Following the path clockwise takes the visitor past markers indicating the cardinal directions, as well as statues and landscape features indicating the routes that the Mescalero and Diné traveled.

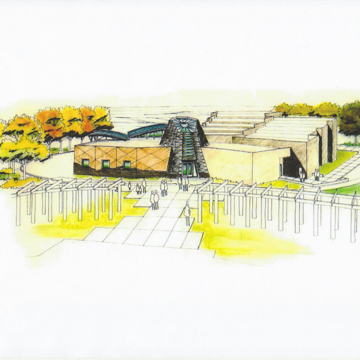

The visitor center comprises two wings connected by a pyramidal entrance area. Sloan’s original design for the entrance featured hundreds of glass panes shaped like the facets of a crystal—Native Americans have traditionally used crystals to gain understanding and reflect upon life. The mullions would have been arranged diagonally, horizontally, and vertically to imitate the random ordering of branches in the brush shelters that the prisoners at Bosque Redondo built for themselves. Budget constraints led to the replacement of the glazing with metal siding. The western wing includes offices, a community space for the village of Fort Sumner, and an observation deck overlooking the Pecos, while the eastern wing, which was completed by Edward Aragon, contains the museum’s exhibits.

The site of the old fort is located directly to the northwest of the Bosque Redondo Memorial. Billy the Kid was murdered there in 1881, and his grave may be found at the Old Fort Sumner Museum, which is located a quarter of a mile from the memorial to the northeast. Work is underway to create an interpretive program that will explain the different historical layers of old Fort Sumner and clarify their relationship to each other. But as of early 2017, the chief obstacle to the success of the memorial remains the absence of its intended landscape design. As Sloan has noted, “the landscape is the memorial,” and it is hoped that budgetary issues will soon be resolved so that the brilliance of his vision can be fulfilled.

The memorial is open to the public during regularly scheduled hours. A permanent exhibition opened in 2022 and, through continued partnership with Navajo Nation and the Mescalero Apache Tribe, expanded the following year.

References

Aragon, Edward. Personal communication, March 14, 2017.

Chilton, Tom. Personal communication, March 14, 2017.

Cortese, Mary Ann. Personal communication, March 14, 2017.

Malnar, Joyce Monice, and Frank Vodvarka. New Architecture on Indigenous Lands.Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Sloan, David. Personal communications, December 18-30, 2015.

Smith, Eliza Wells. “Perspective:The Soul of a Community.” El Palacio 111, no. 4 (Winter 2006): 20.

U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Draft Long Walk National Historic Trail Feasibility Study/Environmental Impact Statement. Santa Fe, NM: U.S. Department of the Interior/National Park Service, January 2009.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.