Pueblo Bonito (Spanish for “Beautiful Town”) is the most famous pre-Columbian building in North America. One of the largest first-order Chacoan great houses, it lies roughly at the center of “downtown” Chaco Canyon. Once thought to be a communal village, Pueblo Bonito is now interpreted variously as a palace, as a political and ceremonial center, and as an occult machine that employed movement, shadow and light, geometry, and symmetry to manipulate geomantic energy.

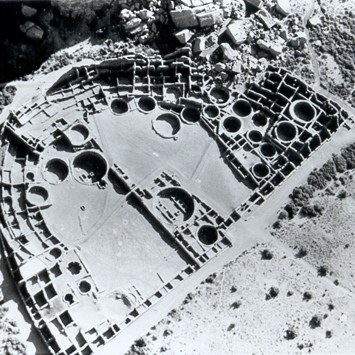

Built in phases between circa 860 and circa 1130, Pueblo Bonito has over 350 ground-floor rooms, and might have numbered as many as 650 to 800 rooms in a structure that rose four stories on its north and east sides. The earliest construction, known as “Old Bonito,” was a two-story structure on the north side; when later additions extended this structure to the southeast and southwest, Old Bonito was incorporated within a taller room block. Reconstructions that depict Pueblo Bonito with stepped, ascending terraces are likely inaccurate, since its final form was probably more monolithic and integrated.

The resulting D-shaped building covers nearly two acres, measures 500 feet at its base, and is organized around a monumental south-facing plaza. Framed by the continuous arc of curved room blocks to the north, east, and west, this plaza is bisected by a wall aligned with the north-south cardinal directions; the plaza’s south wall is just as precisely aligned with the rising sun at the Spring and Fall equinoxes. Distributed around the plaza and reaching deep inside the flanking room blocks are four great kivas, including two abutting the north-south wall, and 32 smaller kivas.

The sandstone used to construct the massive walls of Pueblo Bonito came from the cliffs of Chaco Canyon. Old Bonito is built with Cliff House Sandstone, a durable stone taken from the upper section of the cliffs that fractures easily into tabular pieces. Large, irregular slabs were chipped into shape, stacked with mud mortar, finished with spalls laid into the mortar to even out the face of the walls, and then plastered over.

The intermediate phases of Pueblo Bonito also employed Cliff House Sandstone, but in a core-and-veneer structure that was much more stable than the irregular masonry of Old Bonito. Outer walls of tabular ashlars tightly interspersed with spalls were then filled with an adobe and rubble core; to support the weight of later construction, some lower rooms in Old Bonito were filled in.

The final phases of Pueblo Bonito used the same core-and-veneer masonry, except that its stone was taken from the bottom of the Chaco Canyon cliffs, was lighter in color, and was soft enough to be pecked into blocks. The sandstone walls were roofed with pine beams laid over with saplings, brush, and earth.

If Pueblo Bonito was not a village, then what was it? The dominant paradigm in Southwestern archaeology applies an evolutionary model to explain how prehistoric architecture changed over time into the pueblos that exist today. As a ruin that superficially resembled the communal dwellings at Taos, Hopi, and other historic pueblos, Pueblo Bonito was interpreted as the architectural ancestor of these buildings. Yet Pueblo Bonito exhibits a number of characteristics that are inconsistent with a domestic function.

First, though Pueblo Bonito was built in phases, its consistent and coherent final form indicates careful planning rather than an organic result of multiple families making ad hoc decisions over many generations in response to changing needs.

Second, Pueblo Bonito was expanded in complex building campaigns that often coincided with other construction projects in the canyon. The simultaneous demand, both for large quantities of materials and for large numbers of artisans and unskilled laborers, points to a coordinated centralization of economic and social resources.

Third, Pueblo Bonito’s precise alignments with true north and the solar equinoxes suggest that individuals with esoteric knowledge participated in planning a building whose significance was at least in part cosmological.

Fourth, Pueblo Bonito is distinguished by unusual architectural details, such as four different door types, including T-shaped doorways and corner doorways, which were difficult to build and required skilled craftsmanship.

Fifth, whereas the rooms in Old Bonito were irregular and small, the rooms constructed in subsequent phases were uniformly large and linked in galleries with doorways that are axially aligned to create sightlines extending the length of each gallery.

Sixth, most of these rooms were without hearths and have yielded few domestic artifacts. Conversely, the rooms in Old Bonito contained most of the elite burials, exotic grave goods, and ritual objects that were found in the building. Thus, neither suggests common domestic use.

Seventh, only 50 to 60 burials have been found in and around Pueblo Bonito, rather than the multiple burials to be expected if it housed large numbers of people.

All of this makes Pueblo Bonito a special, and highly specialized, place. Its formal complexity, great kivas, and cosmological features all suggest it was an instrument of ideological, religious and political power. But exactly how Pueblo Bonito functioned remains a mystery. Without any known analogs in North America, Pueblo Bonito’s closest parallels could be in the pre-Columbian civilizations of Mesoamerica.

This National Park Services site is open to the public during regularly scheduled hours.

References

Fowler, Andrew P., and John R. Stein. “The Anasazi Great House in Space, Time, and Paradigm.” In Anasazi Regional Organization and the Chaco System, edited by David E. Doyel, 101-122. Anthropological Papers No. 5. Albuquerque: Maxwell Museum of Anthropology/University of New Mexico, 1992.

Judd, Neil M. The Architecture of Pueblo Bonito. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Vol. 147, No. 1. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1964.

Judd, Neil M. The Material Culture of Pueblo Bonito.Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Vol. 124. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1954.

Lekson, Stephen H. The Chaco Meridian: Centers of Political Power in the Ancient Southwest. London: Altamira Press, 1999.

Lekson, Stephen H. “Introduction.” In The Architecture of Chaco Canyon, edited by Stephen H. Lekson, 1-6. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2007.

Neitzel, Jill E. “Architectural Studies of Pueblo Bonito: The Past, the Present, and the Future.” In The Architecture of Chaco Canyon, edited by Stephen H. Lekson, 127-154. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2007.

Pepper, George H. Pueblo Bonito. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol. 27. New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1920.

Stein, John R., Dabney Ford, and Richard Friedman. “Reconstructing Pueblo Bonito.” In Pueblo Bonito: Center of the Chacoan World, edited by Jill E. Neitzel, 33-60. Washington: Smithsonian Books, 2003.

Stein, John R., Judith E. Suiter, and Dabney Ford. “High Noon in Old Bonito: Sun, Shadow, and the Geometry of the Chaco Complex.” In Anasazi Architecture and American Design, edited by Baker H. Morrow and V.B. Price, 133-148. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1997.