During the first decade of the twentieth century, Frank Lloyd Wright produced some of his most important work, including the Martin House in Buffalo (1903–1905) and the Robie House in Chicago (1908–1910). The Westcott House in Springfield, built in the period between those designs, illuminates the evolution of Wright’s Prairie Style and is his only Prairie design in Ohio. The commission was managed from his Oak Park studio.

During the mid- to late nineteenth century, Springfield led the nation in the production of farm machinery. But Springfield’s early-twentieth-century economy shifted away from agricultural implements to include the publishing, trucking, and automobile industries. Executives of many of these companies built their homes along East High Street, and by the time Burton and Orpha Westcott commissioned Wright to design their own High Street residence in 1906, it was already the most fashionable street in town.

The Westcott family had moved to Springfield from Richmond, Indiana, three years earlier, when Burton took a prominent position with the newly established American Seeding Machine Company. Similar to the International Harvester merger of the same period, this new corporation brought together some of the top leaders in implement manufacturing. In Springfield, Burton quickly became involved in civic endeavors, and ultimately served as the city’s mayor in the 1920s. He also moved his family business, the Westcott Motor Car Company, from Richmond to Springfield in 1916. The company soon became known for their luxury touring cars.

In 1910 Frank Lloyd Wright featured the Westcott House in his famed Wasmuth portfolio (Berlin), including renderings of the front facade, floor plans, and a site plan, which illustrated how Wright integrates the building into its site by means of a terrace, a lily pond, perennial gardens, and substantial urns for seasonal foliage. One can also see an extensive pergola capped with a wooden trellis that connects the detached garage to the main house, a design element included in only a few other Prairie Style houses. The unusual roofline shows Wright’s awareness of Japanese precedents; the low-pitch hip roof with deep, cantilevered overhangs appears to float above the house’s mass. A wide and low chimney anchors the house to the ground and indicates the fireplace as a center of the home. Characteristically for Wright houses from this period, the location of the entrance is ambiguous. Dual walkways flanking the lily pond, terrace, and an expanse of windows look inviting yet do not lead to an entrance. The actual entrance, on the east side of the house, looks modest and, through the use of a double-hung iron gates, protective of a hidden interior.

Here the guest is introduced to the classic Wrightian sequence of dramatic spaces. From the low and dark entrance, located below the first floor, one proceeds up toward the soaring vertical space of a grand staircase that leads to the private quarters. This, the only vertical space in the house, is crowned by a skylight with three stained glass panels. Both the skylight and clerestory windows above the main entrance have the same simple yet elegant pattern of repetitive squares. The combination of clear and warm amber-colored glass casts a geometric pattern on the walls throughout the day. This illuminated effect is dramatized by the shimmering quality of the encaustic wall finish, which is reminiscent of the brushstrokes of Impressionist paintings.

The living quarters at Westcott House embody Wright’s organic concept of the interior, where the room’s essence is the space enclosed by the walls, not the walls themselves, which are broken and freed from their confining role. In the front three rooms partitions separate functions in a subtle way. The ceiling continues uninterrupted from the library, through the living room, and to the dining area, unifying the three and inviting the eye to explore the space. The living quarters are bound together by the deep, autumnal colors of the walls, dark wood trim, and a consistent geometric pattern. The centrally placed living room features a generous fireplace flanked by inglenook benches, the symbolic heart of the household. Here the occupant is offered a complex view through bands of wood casement windows on the south, east, and west walls. There is a shoji-like quality to these windows, which are designed as a repetition of squares that frame vistas to the outdoors.

Typical for a Prairie Style dwelling, Wright introduced a number of impressive built-in furniture pieces custom made for the house. A bookcase, china cabinets, a buffet, a library table, and the playroom table and chairs share the same level of geometric detail and stained oak wood-grain pattern. The most impressive piece is a dining room table that was described in a 1918 newspaper article: “The corners of the table were filled with yellow mums, canopied with art glass, which proved quite effective.” In the Westcott House dining room Wright created an intimate environment by enclosing the dining space with high back chairs and incorporating stained glass electric lamps wired through the table. He used the same concept for other Prairie Style houses like the Robie House in Chicago and the Meyer May House in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

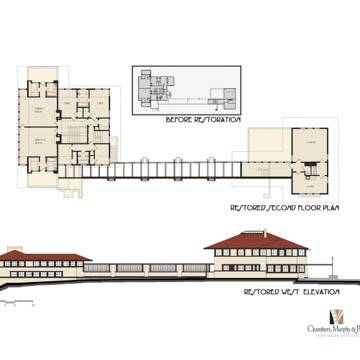

The second floor comprises six bedrooms and four bathrooms. Master bedrooms with mirrored floor plans occupy the front portion of the house. Both have matching private bathrooms and closets with built-in storage. Corresponding sleeping porches connect to both rooms. The cantilevered roofs of these porches show Wright pushing materials to their limits. Two years later, for the terraces at the Robie House, he replaced wood with steel and was able to heighten the drama of the cantilever. For the Westcotts’ two children Wright placed bedrooms on the northwestern corner of the floor, connected through a shared bath. The servant’s quarters, just beyond the back servant staircase, includes two small bedrooms and a shared bath.

The 1920s were not fortunate for Burton Westcott. In 1923 his wife died unexpectedly from surgical complications. Problems with Wescott Motors soon followed, forcing him to close the company in 1925. He died in his home in 1926, at the age of 57.

In the late 1940s, the Westcott House felt victim to the postwar housing crisis. The house that once exemplified a revolutionary concept of open space was divided into seven apartments, an extreme alteration that utterly undermined Wright’s original architectural intentions. In the new century, through the cooperative effort of local citizens and the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy, the Westcott House Foundation was established in 2001. The foundation acquired the house and began a five-year restoration collaboratively supervised by two Ohio architectural firms, Chambers, Murphy and Burge Restoration Architects of Akron and Schooley Caldwell Associates of Columbus. The restoration architects confronted numerous challenges, such as the immediate need for structural stabilization, a complete roof restoration, and new heating and cooling systems. They removed the additions that had altered the original design, recovered wall treatments, and reconstructed furniture. The Westcott House opened as a museum in October 2005.

References

Siek, Stephen. “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Westcott House in Springfield.” Ohio History87, no. 3 (Summer 1987): 276–293.

Wojcik, Marta. The Westcott House: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie House in Ohio. Wilmington, OH: Orange Frazer Press, 2007.