You are here

Cornelius Vanderbilt II House (The Breakers)

In the 1890s, Richard Morris Hunt was considered by fellow professionals and patrons alike to be the dean of American architects. In a career stretching over three decades, he introduced a number of influential styles, culminating in his elaborately palatial residential designs of the late 1880s and 1890s, upon which his national reputation is based. Newport was the locale for numerous Hunt buildings, many of which survivel intact; through them we can trace the evolution of his career from his early training in Paris to the mature, fully developed style of his later years, a style that is forcefully expressed in The Breakers, the summer “cottage” he built for Cornelius Vanderbilt II. Arguably Newport's most famous private house and completed just before Hunt's death in 1895, The Breakers is one of the capstone designs of his professional life, as it embodies lucidly expressed functional planning on a grand scale, a sophisticated vocabulary of sculptural ornament, and Hunt's hallmark European-derived historicism.

The earlier wood-frame house named The Breakers, which Cornelius Vanderbilt bought in 1885, was radically different from the structure we know today. Designed in 1877 by the Boston firm of Peabody and Stearns and originally owned by Pierre Lorillard, it incorporated a variety of textures and turreted shapes informed by the values of the Queen Anne revival, then in vogue. When it was destroyed by fire in 1892, Vanderbilt commissioned Hunt to design a new house—part summer retreat, part family seat—on the same site. (All that remains from the earlier era is the freestanding playhouse, also by Peabody and Stearns, a one-story gabled confection with outsized columnar carvings.) Hunt produced a number of different designs for the project (the drawings of which still exist), including one version with a French aspect and another, similar to what was eventually constructed, in the style of a sixteenth-century Genoese palazzo.

Surpassing in size Hunt's recently completed Marble House, built for Cornelius's brother William and his wife, Alva, on nearby Bellevue Avenue, The Breakers, at seventy rooms, conformed rigorously to its conception as family seat, with Vanderbilt references everywhere visible in the exuberant sculptural details. Not surprisingly, given the fate of the original building, the new Breakers was designed with innovative fireproof and technical features, such as Guastavino tile vaulting for some of the porches and steel-frame reinforcement.

Formal and balanced in its overall plan, the Hunt design adds variety where none might be expected. Each facade is interrupted by significant features, like the broad porte-cochere at the entry, the circular depression of the laundry court off the service wing, and the two-story trellised bay overlooking the formal gardens. The massive bulk of the building is compromised by the push-pull of setbacks and projections on the elevations and by relief surfaces with echoes of Renaissance forms. The most developed facade, as might be expected of a summer residence, faces seaward. Here, the central void of a mosaic-tiled loggia is defined by a triple arcade and flanked by end pavilions. The easy rhythms of the arches on the first story are quickened by the doubled openings of the second story, just as the Doric order employed below is shifted to the Ionic above.

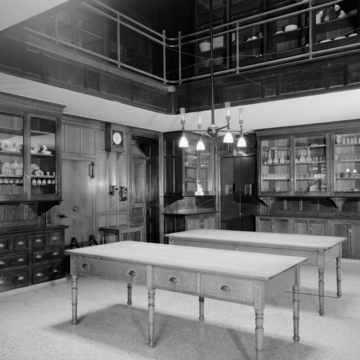

The interior of the house shows the same concept of balanced variety: a clear, rational core in the vertical rise of the great hall, off of which spring rooms of various shapes and functions, the same scheme Hunt used in the earlier Ochre Court (see entry, above). Here the effect is even more monumental; the walls are supported on broad spans of tripled arches, and grand Corinthian pilasters run from tall bases up to a garlanded cornice more than two stories above. What is meant to grab and hold the attention is not spatial invention, but the luxurious combination of variegated stone, detailed carvings, gilded surfaces, and elaborate metalwork on a larger-than-life scale. Hunt's mastery is that of a great orchestral conductor who seamlessly blends overpowering elements into a unified but stirring experience.

In the decades following Hunt's death, Newport mansions like The Breakers were generally regarded as glorious excesses of the nouveau riche, pseudo-princely stage sets for a self-styled aristocracy of a new American class of industrial captains. Recent reinterpretations show that The Breakers reveals much more in its myriad layers of social impact: on the evolving townscape of Newport; on the artisans imported from abroad to execute its ornament and decor, sculpture and furnishings; on the rise of architecture as a profession and its relationship to powerful male and female clients; on the use of new technologies moving toward modern building practices; on the emergent servant corps who oversaw daily life in these large residents; and finally on the way in which the grand mansions reflected, in their construction and imagery, the desires, values, and social structure of the age.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.