Monarch’s Cave reveals the living patterns of Ancestral Puebloans during the period between 1150 and 1350. Orientated toward the southwest end of a canyon in the Comb Ridge monocline, the cliff dwelling receives maximum winter sun, is situated above a water source, and is strategically tucked into a defensible spot. The cave is one of the larger dwelling places in Comb Ridge. Elaborate petroglyphs and pottery shards abound, as do 900-year-old metates (used to grind corn), corncobs, sharpening grooves, and a trash pit, all of which provide clues about the everyday life, rituals, landscape intelligence, food security, defense strategies, arts, and self-representation of the Anasazi.

Comb Ridge offered the Anasazi hospitable environs. Springs, seeps, and pools provided water; sheltered ravines and deep alcoves gave protection; juniper and cottonwood provided firewood; and sage and yucca served many of their nourishment and medicinal needs. The monocline stretches 80 miles across the Colorado Plateau in southeast Utah and northeast Arizona. Where State Route 95 and U.S. Highway 163 intersect it, Comb Ridge reaches 700 feet in height. On the western side, the cliffs are sheer and the rock strata, which includes red Wingate sandstone, are dramatically exposed. On the eastern side, where a layer of white Navajo sandstone is visible, the slope is gradual (20 degrees) and the monocline splits into short box canyons. Tucked inside many of them are the remains of Anasazi settlements.

The dwelling at Monarch’s Cave lies on a ledge that widens and narrows below a sandstone overhang. It is approached via a steep climb from the bottom of the canyon to the west end of the settlement. This portion of the ledge is narrow and relatively exposed to the elements; it is separated from the grand alcove toward the southwest by 25 feet of slippery rock. A number of handholds and toeholds chipped out of the rock face connect the two sides of the ledge that all but disappears in this stretch. Access to the site is thus slow and difficult—an added defense strategy.

On the entrance ledge only remnants of granaries remain; on the second ledge, however, are more expansive ruins. The south end has three masonry rooms, one with a rounded front wall that may have been part of a kiva. The other two rooms seem to have been designed for habitation. The north end has several rooms with interior plaster. A large defensive wall, with loop ports, stands in front of the alcove. Just below the pueblo, on the canyon floor, is a grotto with a small pool of water.

Walls were built using evenly spaced, well-sized stones with either smoothed or pecked surfaces. But the masonry varied greatly, and rough and superior types of stone are found side by side, indicating that the Anasazi had to share their location with other groups or possibly make changes to their structures in order to accommodate an influx of people. In addition to defensibility, building habitations against rock walls offered clear environmental advantages: aside from providing shelter from the rain for people and food supplies, the rear of overhangs retain warmth more efficiently during the winter and provide deep shade during the summer. When compared to the rigors of the desert floor, life in canyons was certainly more comfortable. The rooms have small openings for ventilation and the wooden roofs are made of juniper beams and twigs covered with mud that has been mixed with grass and stone chips. Marble streaking in the sandstone canyon wall and overhangs produces a spectacular visual effect and ties the variations in the red masonry and mud plaster to the site.

While the dwelling dates from around 1250, the petroglyphs suggest that Anasazi had been using the alcove periodically for hundreds of years before. The ceiling of the bigger alcove contains a dozen red handprints and a large pictograph. On its northern wall are two more pictographs. One depicts a broad-shouldered figure with Hopi-like hair whorls; the other is a man-shaped petroglyph pecked into the face of the rock. These anthropomorphic representations date from the eighth century.

In another canyon less than a mile south of Monarch cave, still on the east face of Comb Ridge, is a processional panel that consists of 179 figures spread across an approximately twenty-foot-long section of the cliff face. Figures proceed from three directions to a circle in the center. Each tiny figure represents a person or an animal. Thirty-seven people march in from the west side, 129 meet them from the east, and a small number approach from below. The red spots on the big animals indicate this panel may depict a hunting scene.

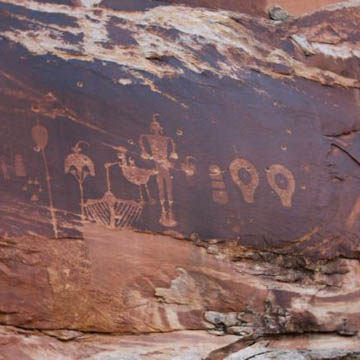

In yet another canyon, five miles further south, is the Wolfman Panel, dating to the eighth century. Along with the monumental central human figure, the panel includes depictions of a mask, yucca plant, basket, mountain lion or canine track, birds, elaborate staffs, and two symbols variously called keyholes, lobed circles, or drooping eyes. Sally Cole, who has studied petroglyphs in Utah and Colorado, suggests that this panel is heavy with fertility symbolism.

This area is currently under the protection of Bureau of Land Management.

References

Ferguson, William M. The Anasazi of Mesa Verde and the Four Corners. Niwot: University Press of Colorado, 1996.