You are here

Bryce Hospital

The original building of Bryce Hospital, now a part of the University of Alabama campus in Tuscaloosa, is one of the state’s most significant architectural landmarks. Prior to its construction, the state had no facility to treat the mentally ill. In 1852, after lobbying by Dorothea Dix (1802–1887), a national advocate for appropriate mental health treatment, Alabama Governor Henry W. Collier (1801–1855), and Senator Robert Jemison Jr. (1802–1871), the Alabama legislature passed an act to provide for the construction of the Alabama Insane Hospital. The asylum was to be located in Tuscaloosa on 326 acres of land adjacent to the University of Alabama.

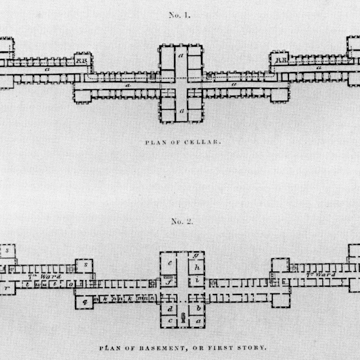

The hospital committee consulted with Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride (1809–1883), the foremost authority on asylum design. In collaboration with architect Samuel Sloan, Kirkbride agreed to provide a plan for the proposed hospital. The innovative design received national recognition when Kirkbride published it as the “Alabama Plan” in his seminal On the Construction, Organization, and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane (Philadelphia, 1854). By the end of the nineteenth century, over 100 public and private mental hospitals in the United States and Canada exhibited architectural features directly traceable to the Alabama hospital plan.

The design of Bryce Hospital is significant for both American architecture and psychiatry. Designed and executed at the height of a reform movement in psychiatry known as “moral treatment,” the 250-bed hospital reflected progressive ideals concerning the housing and treatment of the mentally ill. Moral treatment proponents placed great emphasis on architecture; the design of an asylum was thought to play a key role in the healing process.

Although Sloan created the plans for the Italianate hospital in Philadelphia, Sloan’s partner, John Stewart, supervised the construction of the massive building erected in Tuscaloosa between 1853 and 1861. The Alabama Insane Hospital was the first fully realized linear plan hospital erected in one building campaign and it is characterized by its distinctive configuration of a domed central pavilion, flanked on either side by three stepped back wings joined by cross halls. It is built of locally quarried sandstone and brick once covered with tinted stucco and penciled to imitate ashlar. Paired wooden brackets support the wide eaves of the tin-covered roof. The central pavilion originally featured an ornate cast-iron balcony over the main entrance. In 1884 Dr. Peter Bryce (1834–1892), the hospital’s first superintendent (for whom the building was renamed in 1893), replaced the balcony with an imposing portico of colossal brick, stucco-covered Tuscan Doric columns.

The central pavilion contained administrative offices, public visiting rooms, a chapel, staff dining rooms and kitchens, and dining rooms for the least afflicted patients. It also housed the superintendent’s quarters on the third floor. Its most dramatic feature is the large dome that provides unparalleled views of the surrounding countryside. Moral treatment proponents believed that landscaped grounds and beautiful vistas had a soothing effect upon the troubled mind and patients, with supervision, were occasionally allowed visits to the dome. Directly below the dome in the attic are three enormous metal water cisterns that were once part of the elaborate water works that provided running water to all parts of the building.

Patients were housed in the wings located on either side of the center pavilion. They were segregated by sex, with men in the wings on the left and women on the right, and by the severity of their illnesses, with the most severely afflicted patients in the outermost wings, where their disruptive behavior and noise would be less likely to disturb other patients. Theoretically, as patients improved from moral treatment they were moved to the wings closer to the central pavilion, where they could interact more freely and eventually return to normal life. The wings—illuminated by gas lights, heated by steam, and cooled and ventilated by steam powered fans—featured individual rooms for patients, wide corridors, an activity or “day” room, a nurse’s station, bath, drying room, and water closet.

Bryce Hospital began accepting patients in 1861, before the completion of the heating and lighting systems and the construction of outbuildings needed for farming operations. The number of patients was small in the early years, and Dr. Bryce accommodated them in makeshift fashion in completed sections of the building. State funds were cut off during the Civil War but because labor-like activities were considered an important part of patient therapy, hospital operations continued. Male patients were involved with all aspects of farming, including growing crops and tending livestock on the institution’s large farm. Female patients were kept busy with domestic chores including sewing, cooking, and cleaning. Dr. Bryce rightly asserted that it was the hard work of the patients that allowed him to keep the hospital open during the war. In 1864, a portion of one of the unoccupied east wings of the building was used as a Confederate hospital. Ellen Bryce, wife of the superintendent, and other Tuscaloosa matrons served as nurses.

In the late nineteenth century, the idealistic and humanitarian goals of “moral treatment” were eroded by overcrowding, underfunding, and the reality of lifelong patients. Referred to as the “custodial era,” more attention was given during this period to simply housing and feeding thousands of mentally ill patients than to attempts to cure them and return them to society. To accommodate the increasing numbers of patients, Dr. Bryce, acting as his own architect and using patient labor whenever possible, constructed numerous additional wings that extended from the north, east, and west sides of the original building. Though they provided shelter for hundreds of new patients, they undermined the integrity of the original 250-bed hospital as an “instrument of treatment.” Most of these wings, as well as many of the outbuildings associated with the hospital, were demolished in the 1990s.

In the early twentieth century, the “biological era” in American psychiatry, it was thought that modern medicine held the cure for insanity. Many advances were made in the treatment of patients, but lack of funding and severe overcrowding was endemic in asylums throughout the country for most of the century. By the 1960s, the Bryce Hospital campus was severely congested with scores of additional buildings housing, at one point, more than 5,000 patients. In the last thirty years of the twentieth century, new concepts in the treatment of mental illness, the widespread use of drug therapy, and an emphasis on decentralization shifted the focus of mental health services away from large state mental hospitals to smaller community-oriented mental health centers.

In 1971 Bryce Hospital again gained national recognition when this venerable institution—once one of the most progressive and imitated hospitals in the country, but now underfunded and grossly overcrowded—became a respondent in a long and involved federal lawsuit, Wyatt v. Stickney. The lawsuit established minimum standards for adequate treatment for mentally ill and mentally retarded patients institutionalized in Alabama hospitals. This famous and groundbreaking lawsuit resulted in the improvement of care and treatment of these individuals and it ultimately played a key role in the revolution of mental health care throughout the United States.

In 2010 the Alabama Department of Mental Health and Retardation sold Bryce Hospital and its campus to the adjacent University of Alabama. Due to strong support from local and state preservationists, the University agreed to retain the central portion of the nineteenth-century hospital in the purchase agreement. In 2014 and 2015, however, university officials demolished the outermost of the trio of stepped back wings to accommodate a roadway. The remaining portions were remodeled inside for academic purposes and became the Peter Bryce Building. A small museum dealing with the history of mental health in Alabama is incorporated into the building.

References

Mellown, Robert O. “The Construction of the Alabama Insane Hospital, 1852–1861.” Alabama Review 38 (1985): 83-104.

Mellown, Robert O. Historic Structures Report: Bryce Hospital, Tuscaloosa, Alabama.Heritage Commission of Tuscaloosa County with support from Alabama Historical Commission, 1990.

Mellown, Robert O. “Mental Health and Moral Architecture.” Alabama Heritage 9 (1994): 5-17.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.