Built in 1957, Kellogg High School is one of Idaho’s best and earliest examples of mid-century modernism. Here the early-twentieth-century ideals of Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and Mies van der Rohe come to fruition through a plan that harvests an abundance of fresh air and light while ensuring grand views of the mountains and town below. The building was designed by leading educational architects Perkins and Will of Chicago, who envisioned the school as a cultural and lifelong learning center.

For most of its existence Kellogg has been one of the most active silver mining towns in Idaho, with Bunker Hill Company and Sullivan Company as the major employers. In the mid-1950s when the mines were at peak production, Kellogg was nearing its highest population (6,000) and its residents were comparatively prosperous. The city felt confident making plans for future growth and development and this included building an exemplary high school.

School Superintendent Howard Andrews and the Kellogg school board worked with Dr. J.F. Wetzin, Dean of the College of Education at University of Idaho, to survey the school districts in the Silver Valley region. They determined that consolidation was in the best interests of the students with a new high school serving the needs of the merged school district. A central location was selected for proximity to the various valley towns that made up the new district. Jacob’s Gulch, at the west end of Kellogg, is not only accessible, it is relatively sheltered from winds and floods, and has its own water source. Jackass Creek flows south down the gulch’s east edge and drains into the Coeur d’Alene River.

In 1956 Perkins and Will collaborated with the Spokane architecture firm Culler and Gale on the design of the new school. Perkins and Will had established a national reputation starting in 1935 with several noteworthy elementary and secondary schools. Culler and Gale worked locally, mostly on buildings for higher education, government offices, and religious institutions. Their joint philosophy of school design was one of openness, welcome, and ease of access translated into few visual or psychological barriers between interior and exterior. They believed that the best schools provided instruction not merely specialized academic subjects—reading, writing, and arithmetic—but in all areas of life, in the domestic and industrial sciences that students of previous generations had learned from their parents. They also believed that school programs should be tailored to the needs of the community in which the school was placed.

In Kellogg, this meant a building that took advantage of the mountain views surrounding the site and facilities that taught students skills that would be useful to them in mining, business, and home management, but also served students preparing for college. Beyond the student body, the school was envisioned as a place that would also serve Kellogg’s adult population, for social events and vocational training. Indeed, the school was viewed as an important part of a city-wide revitalization program.

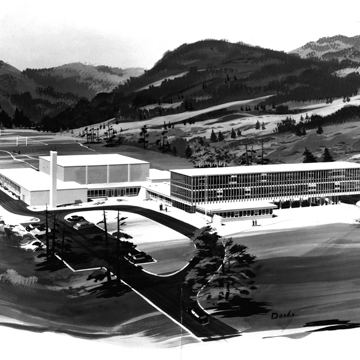

As a campus, the design consisted of four main components: a gym with shops and cafeteria, an administrative wing, an outdoor courtyard, and a classroom wing. These components slip past one another in a de Stijl-like composition that has parallels to the widely publicized 1952 Lever House in New York by Skidmore Owings and Merrill and even to the Bauhaus itself (1926, Walter Gropius). The gym is located just north of the administrative wing and extends to the west. This section also includes the cafeteria, kitchen, and music room on the eastern side, with metal and wood shops on the western side sandwiching the gymnasium in between. The vaulted gym features concrete support buttresses that cross into the cafeteria. It is fronted by a foyer-hallway that opens out into a courtyard formed by the administrative wing on the east and the boiler room and smokestack on the west. This separates the noisiest parts of the campus from the classrooms.

The administrative wing contains the main entrance, the library, the main offices, and the home economics labs and runs north to south, parallel to Jackass Creek. The wing slides underneath and perpendicular to the classroom wing that it carries above. Vertically joining the two wings are a stair and elevator core. The western end of the classroom wing cantilevers over the administrative wing to define the main entrance. The remainder of the classroom wing is elevated on pilotis forming a breezeway that is bookended by a one-story concrete retaining wall built into the side of the hill.

Originally, the exterior skin was floor-to-ceiling glass installed as a tripartite system in which the middle panel was twice the height of the top and the bottom panels. As at the Bauhaus and so many other modernist buildings, the window wall is independent of the floor plates and structural columns behind. Here, the slender vertical mullions were concealed by T-profile, painted steel beams that are attached to the building’s exterior and extend the entire height of the building face. This element provides vertical emphasis on a primarily horizontal structure and a certain amount of sun glare in the morning and afternoon. So successful was the curtain wall that Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company (PPG) featured it prominently in a 1958 advertisement, boasting that “in forward-looking communities across the land, students find new interest in bright, modern schools like Idaho’s Kellogg High. Daylight floods their classrooms through whole walls of PPG glass.”

The transparency of the modernist window scheme was greatly compromised in 2008 when the school district received a bond to make the high school more energy efficient. The new window system replaced the top quarter and bottom third of the glass wall with solid insulated wall. Interior walls with doors were also added at this time to separate the classrooms from the corridor, and an acoustical tile drop ceiling was installed level with the new top of the windows.

Today, the classroom units are separated by interior masonry unit walls where chalkboards and public address system components are attached. The wall separating the classroom and the corridor consisted of lockers for students on the corridor side, and storage cabinets with bypass doors on the classrooms side. Originally, these locker bays were raised off the ground and stopped three feet short of the ceiling, enabling light from the south-facing exterior wall to bounce across the ceiling and floor and out the north-facing window wall. There were no doors separating the corridors from the classroom. This changed in 2008 when the remodel filled in the gaps with sheet rock walls.

The walls of the administrative wing consist of brick on the bottom third of the exterior face with clerestory windows occupying the upper third. The exceptions occur at the entrances and the exterior wall of the cafeteria, where floor-to-ceiling glass was installed. In one section of the administrative wing the upper two thirds consist of large windows with the bottom third of the wall clad with brick. Any east or west sunlight that is not screened by the sides of the gulch is mitigated with curtains.

Before the 2008 energy upgrade, the exterior wall of the gym’s foyer was floor-to-ceiling glass. The wall between the gym and the foyer, which contains the school’s trophy case, was glass as well, and this not only enabled one to look straight through the trophy case, it meant that the gym received a certain amount of natural light at the floor level. The shops on the west side of the gym have the same one-third brick, two-thirds glass walls as the rest of the ground floor structures.

In 1963 architects Culler, Gale and Martell and engineers Norrie and Davis added a new classroom block perpendicular to the original classroom wing on the east end of the classroom wing up on the hill. They also expanded the library to the south, effectively doubling its size. While the classroom addition retains the same general floor plan as the original school building with single-loaded corridors and floor-to-ceiling windows, the interior sensibility is not matched due to changes of materials. The ceiling is carried by four-foot-thick, wood-laminate beams that rest on steel pillars. The area between the steel pillars is filled in with concrete masonry units. The north and south walls are brick-clad rather than glass. Although lockers are installed on the walls between the classrooms and corridor, they are concrete masonry units from floor to ceiling, with metal doors for each classroom. The west windows on the corridor were the same as those on the original classroom wing, but the east windows in the classrooms are different: tall, but with four horizontal panes extending the width of each sash.

Despite changes over the years that reflect shifting priorities of comfort and cost-efficiency, the Kellogg High School still retains its essential modernist sensibility.

References

Architects Alliance, PA. Kellogg High School Cafeteria Plans. 1993. Kellogg School District, Kellogg, Idaho.

Architects West. Kellogg High School Additions and Modernizations. 1998. Kellogg School District, Kellogg, Idaho.

Caldwell, Albert, and Billie Erickson. Interview by Arwen Bloomsburg. Kellogg, ID, October 11, 2014.

Cantrell, Lee. Email interview by Arwen Bloomsburg. Moscow, ID, October 30, 2014.

Chapman, Ray. History of Kellogg, Idaho, 1885–2002.Kellogg, ID: Chapman Pub, 2002.

City Planning Commission. The General Plan, Kellogg, Idaho.Kellogg, ID: n.p., 1957.

CTA Architects Engineers. Kellogg High School Window Replacement Plans. 2008. Kellogg School District, Kellogg, Idaho.

CTA Architects Engineers. Kellogg High School HVAC System Replacement Plans. 2008. Kellogg School District, Kellogg, Idaho.

CTA Architects Engineers. Kellogg High School Band Room Remodel Plans. 2008. Kellogg School District, Kellogg, Idaho.

Culler, Gale, Martell, Ericson – Architects, Kenneth P. Norrie – Engineer.Spokane, WA: Culler, Gale, Martell, Ericson – Architects, Kenneth P. Norrie – Engineer, 1967.

Culler, Gale and Martell. Kellogg High School Plans. 1963. Kellogg School District, Kellogg, Idaho.

g.d. longwell – architects pllc. Remodeling for Kellogg High School. 2003. Kellogg School District, Kellogg, Idaho.

g.d. longwell – architects pllc. Special Needs Classroom, Kellogg High School. 2009. Kellogg School District, Kellogg, Idaho.

Lopez, Frank G. AIA. “The Problems of School Sites.” Architectural Record121, no. 1 (1957): 189-206.

Perkins, Lawrence B., and Walter D. Cocking. Schools.New York: Reinhold, 1949.

Perkins, Lawrence B. Workplace for Learning.New York: Reinhold, 1957.

Perkins & Will and Culler & Gale. Kellogg High School Plans. 1957. Kellogg School District, Kellogg, Idaho.

Shonfeld, Robert B. “Monument to Reawakened Pride.” The Nation’s Schools59, no 2 (1957): 66-73.

“New Kellogg High School is Recognized Nationally.” Spokane Daily Chronicle, March 15, 1957.