You are here

Joliet Correctional Center

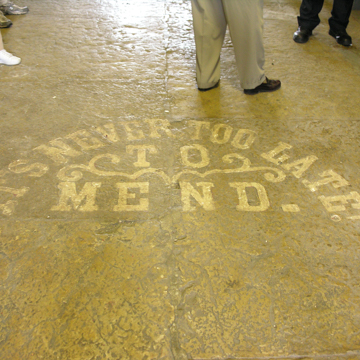

In the nineteenth century a prison was rarely just a fortified building to incarcerate men and women; it was an iconic structure meant to convey the strength and seriousness of the law. The prison was also a hub of local industry—prisoners were hired out to business owners to perform both menial and skilled labor. And the prison was the scene of various holiday celebrations and social activities for residents of the surrounding city, providing the prison warden with an elevated social status in the community. The Joliet Correctional Center is an excellent example of this type of all-encompassing prison program.

Illinois achieved statehood in 1818 and by the 1850s the state’s prison at Alton, in western Illinois, was severely overcrowded. In 1857 the General Assembly appropriated money for the construction of a 1,000-cell facility in Joliet, in the northeastern part of the state, close to the booming city of Chicago. The prison was built and run on the cost-efficient “Auburn Plan,” based on that at the Auburn prison in New York: prisoners slept in individual cells but worked together during the day. Contractor Lorenzo P. Sanger oversaw construction using prison labor from Alton.

The Joliet Prison was planned for a 72-acre site just north of the city limits on a large plot of land bounded by Collins Street on the east and the busy Illinois and Michigan Canal and railroad tracks on the west. Directly east of Collins Street was a limestone quarry that provided stone for the prison’s construction (as well as for the complex’s many other buildings). The uniform quality and color of this warm golden limestone gives the entire prison complex the feel of a thoughtfully planned campus.

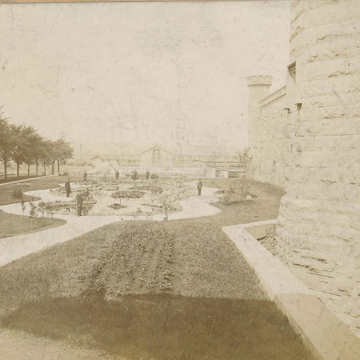

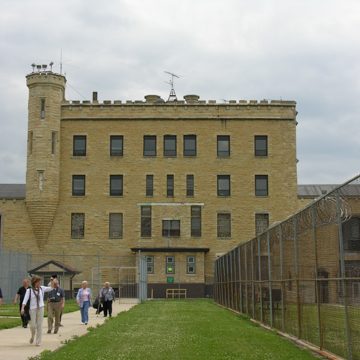

Work began in 1858 with plans by the architectural firm of Boyington and Wheelock. William W. Boyington, one of the few trained architects in Chicago in the 1850s and 1860s, and also one of the city’s most prolific, designed the prison to resemble a medieval castle, complete with rusticated stonework, high walls, crenellated corner towers, stepped buttresses, and a large Gothic Revival porte-cochere on Collins Street. The prison’s three-story main building was flanked by two cell block wings and contained living quarters for the prison warden and his family, an area for processing prisoners upon arrival and departure, and administrative offices. One cell block had four tiers of cells and the other had five.

The immense size of the Joliet Prison and its highly visible location ensured that it became a tourist attraction for visitors to the bustling city and even for residents. Ornamental gardens were laid out in front of the main entrance on Collins Street, making a Sunday stroll through the grounds a favored local activity. The prison was illustrated in the city’s first atlas, published in 1873, and the grounds and public rooms became gathering spots on important holidays. The warden’s annual ball was a sought-after invitation.

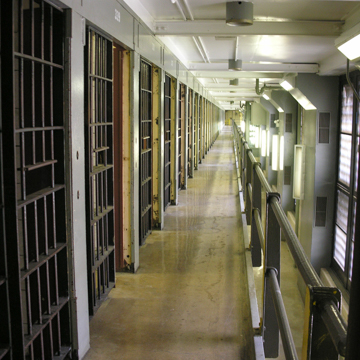

The facility opened in 1858 with just 280 prisoners, but its population quickly exceeded the 1,000 inmates for which it was planned. It housed prisoners of war during the Civil War and by 1866 it was holding 1,104 men and women. Just ten years later, this number had grown to 1,700 (indoor plumbing facilities were not added for another thirty years). With the majority of the small cells now holding two prisoners, it was becoming increasingly difficult for the warden to maintain order. Internal fights, stabbings, and hangings were noted frequently in the local paper.

To meet the challenge of keeping order, an entire village arose within the prison walls: an almost windowless building for solitary confinement, a chapel, a kitchen and dining hall, a bath house, a steam plant, a hospital, greenhouses, a laundry, a library, a storehouse, and a bakery. Eventually there were “honor” dorms for prisoners with more freedom and special privileges. Women were held on the top floor of the main building until the construction of a separate women’s prison in 1894 on the east side of Collins Street. Throughout the life of the prison, up to 1,600 men worked four shifts at the adjacent quarry. Construction of the prison facility was almost continual and many of the buildings erected during the prison’s 144 years of use are still standing today.

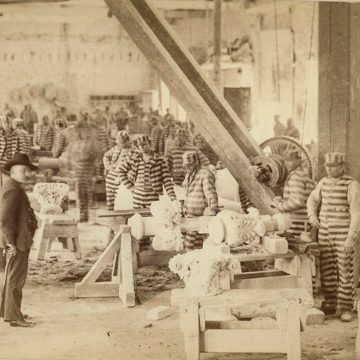

As a major transportation nexus, Joliet was a booming industrial town and the prison participated in this prosperity. In addition to the buildings containing cell blocks and supporting functions, there were numerous structures in which prisoners carried out labor for private industry: a foundry, a stone shop, a cigar shop, a shop producing tin architectural ornament, a wagon-making operation, a cooper shop, a harness shop, a furniture shop, and a very large shoe and boot factory. Except for the open-sided stone shop and the glass greenhouses, these buildings were constructed of Joliet limestone by the prisoners themselves. Northeastern Illinois’s most prevalent building material during the third quarter of the nineteenth century, Joliet limestone remained a popular choice even after brick became widely available. But if the prison buildings were familiar in form and material, they were exceptional in size. The main building and the prison yard walls are still impressive today.

The last structure built at the prison is the 1966 chapel by Edward Dart. The chapel is a simple stone box ornamented with shaped glass blocks arranged into vertical strips. Dart’s work, although a complete contrast to the heavy limestone and Gothic Revival details of the original prison and its subsequent buildings, fits neatly into the prison courtyard. Set close to the western wall, the entrance is deeply recessed at the north end under a blocky overhang featuring a carving of the open Bible. From this northeast corner, a dramatic parabolic copper roof swoops up to a copper pinnacle. The roof is supported by a heavy beam along the ridgeline, expressed in the wrapped copper of the roof itself. Inside is an open sanctuary with plank benches. The brick walls are beautifully ribbed between the glass blocks at the back of the sanctuary, which bathes the space in diffuse light. The sectioned ceiling is finished with tongue-and-groove boards and a series of long white pendant lights. Dart used low-cost materials to achieve dramatic results in this little chapel.

The prison closed in 2002 and in recent years has become a popular site for movie and television productions. Its long-term future is uncertain.

References

“William W. Boyington.” In Biographical Sketches of the Leading Men of Chicago, 215-222. Chicago: Wilson and St. Clair, 1868.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.