The Carissa Mine was once the largest and most productive gold mine in the Sweetwater Mining District near South Pass in central Wyoming. First discovered in 1867, the Carissa Lode spurred the economic growth of nearby South Pass City, which, in its original location nine miles south of the present town site, had been a popular rest stop for weary travelers on the Oregon Trail in the 1850s. Despite South Pass City quickly becoming the largest “boom town” in Wyoming, the mine’s success was short lived. Within a decade of discovery, it was clear the hoped-for success would not be found, and families began to depart the area. Still, many stayed on in South Pass City, clinging to the possibility that more gold might be found. A successive string of owners with fresh goals and money took over the Carissa in the early 1900s, and while the mine produced millions of dollars’ worth of gold, each owner left bankrupt. Finally, in 1954, the Carissa shut down for good, and the last miners and their families departed, leaving South Pass City a ghost town.

Efforts to preserve the mining district and the Carissa Mine began not long after its closing. In 1966, the Wyoming’s 75th Anniversary Commission purchased South Pass City as a gift for the citizens of the state and in 1970, the South Pass City Historic District was created, comprising more than seventy private and public structures associated with the nineteenth-century town. Included in the historic district is the Carissa Mine, about one-half mile northeast of the townsite, with three mine shafts ranging from 90 to 450 feet deep, ten associated buildings, and five support structures.

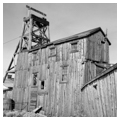

The Carissa Mill, a long rambling structure built for the processing of ore, is the main building at the mine site. It was constructed in 1904 in nearby Atlantic City and moved to the Carissa site in 1929. The timber-framed structure is built in steps on a steep slope, with each of the steps designed for a specific stage in the ore processing. The ore entered the building at the tallest step, located on the highest point of the slope, and passed through successive processes before it exited the building at the lowest point.

Both the roof and the walls of the mill are sheathed in large sheets of corrugated sheet metal, with clerestory windows that allow light into the interior. The tallest portion of the structure is capped with a northeast-facing gable monitor roof, with two levels of doorways in both the monitor and main portion of the eave-end facade. The bottom doorway, located at grade, was for worker access, while the monitor door was where the ore entered via a rail trestle (now reconstructed). The rest of the roof is a series of large gables, running northwest to southeast. The lowest step is capped with a four-dormer shed roof. Graveled drives access double-wide doorways on each of the step levels on the southwest facade of the building.

Connected to the Carissa Mill via the reconstructed wooden rail trestle is the hoist house, a one-story, wood-framed building capped with a side-gable roof. The roof and walls are sheathed in corrugated metal. Attached to the hoist house on the south elevation is the reconstructed shaft house, a two-story, wood-framed structure capped with a gabled roof. The northern portion of the second story has a four-post derrick with a diagonal back-brace headframe extending upward to create a third story. The rail trestle was used to hoist the ore up from ground level, where it was loaded into carts and sent down to the Carissa Mill via the rail trestle.

The State of Wyoming purchased the 200-acre Carissa Mine site from a private owner in 2003, and began a ten-year restoration and reconstruction project, which included reinstalling ore-processing equipment that had been removed and sold when the mine closed in 1954. The interior was restored to the post–World War II period, when the mine and mill were most productive and milled approximately sixty tons of ore per day in three round-the-clock shifts. The reinstalled equipment is now fully functional. The State of Wyoming runs the Carissa Mine as part of the South Pass City State Historic Site, with tours of the mill that include demonstrations of the mid-twentieth-century milling equipment in operation.

References

Rosenberg Historical Consultants. “South Pass City Historic District (boundary increase and additional documentation),” Fremont County, Wyoming. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 2012. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Wyoming Historic Mine Trail and Byway Program. “Goldflakes to Yellowcake Historic Mine Trail.” Interpretive Plan, Summer 2009.