You are here

Gaineswood

Nathan Bryan Whitfield (1799–1868) was probably as close as early Alabama ever came to a gentleman architect in the tradition of Thomas Jefferson or Nicholas Revett. His status as an “amateur” is all the more surprising in that Gaineswood, the house he built for himself, is often acknowledged as one of America’s remarkable neoclassical residences. In fact, Roger Kennedy, in his sweeping 1989 survey Greek Revival America, has gone so far as to label Gaineswood’s richly ornamented interiors as “peerless” in expressing American ornamental ideas of the period.

Skeptics of Whitfield’s expertise as an amateur speculate that he probably engaged one of the region’s prominent architects (both Henry Howard of New Orleans and Prussian-born Adolphus Heiman of Nashville have been mentioned) to produce Gaineswood’s complex spatial scheme. To be sure, he may have sought professional advice over the eighteen years the house was intermittently under construction, but documentary and physical evidence seems to reinforce family tradition that Whitfield was ultimately his own architect. Indeed, free from the restraints of professional convention, he seems to have patiently followed his muse—starting with no grand scheme in mind but producing, in the end, a uniquely individual essay in the Greek Revival.

Born into a prominent North Carolina family, grandson of a congressman, and a graduate of the state university at Chapel Hill (where his father served as a trustee), Whitfield, in the mid-1830s, joined the planter exodus from the worn lands of the Atlantic seaboard to the promising new cotton country of western Alabama. He settled in Marengo County, first in the lower part of the county, then, early in the 1840s, on a 480-acre tract just southeast of the river town of Demopolis—the property he would later name Gaineswood after its former owner, General George Strother Gaines. A key figure during the territorial period and early days of statehood, Gaines had also been U.S. Agent to the Choctaw Indian Nation and a major player in the removal of the Choctaws to the west, beginning in 1831.

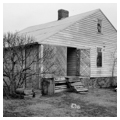

Whitfield and his family first moved into the log house that already stood on the plantation. Variously described as a “cabin” and a “dogtrot,” it may have actually been an open-hall, hewn-log house—perhaps even two stories—similar to a handful of others that survived in the Demopolis area as late as the 1980s. Considered the “mansion” of the plantation frontier, these dwellings were a cut above the stereotypical log cabin. Often, in fact, they were upgraded (or “improved,” in contemporary parlance) with weatherboarding on the outside and interiors trimmed out with chair rails, plastered walls, and handsome mantelpieces. It is unknown whether Gaines’s log house had been improved by the time the Whitfields moved in but it became the nucleus from which would evolve the current mansion. A Whitfield niece, who lived for a time with the family at Gaineswood, recorded in her memoirs that the master of the house, concerned about decay in the original log infrastructure, had it torn away and replaced with conventional frame construction. Most probably this, the earliest section of the house, morphed into what is now the rear or south block of the house—long and low and strangely deferential to the hulking, northward-looking main structure.

Gaineswood’s complex physical development from the mid-1840s to 1861, when the outbreak of the Civil War brought construction to a halt, is impossible to dissect in detail. When Whitfield’s first wife, Elizabeth, died in November 1846, the present dining room and parlor/library are said to have been completed, though it is unlikely the present domed skylights and decorative bas-relief finish were added at this time. Nor is it clear if, by that time, Whitfield already had vaguely in mind the eventual form of the house as it would come into being over the next fifteen years. But rather than a fixed, overarching scheme to be implemented step-by-step, it seems more likely that Whitfield, in the manner of Jefferson at Monticello, may have gradually altered, renovated, and enlarged his residence as inspiration and necessity directed.

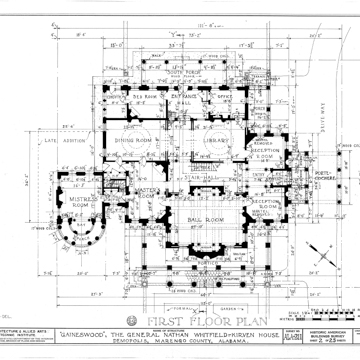

Besides his collection of architectural books, which included Stuart and Revett’s Antiquities of Athens and the works of Minard Lafever, he doubtless absorbed ideas from his travels. Surviving family correspondence reveals occasional trips to the Northeast, not only to Philadelphia but also to Saratoga, Ballston Springs, and other fashionable spas, and down the Connecticut River Valley through Middletown and toward the New England coast. He possibly traveled to New Haven as well, where famed architect Ithiel Town had assembled and generously shared one of the great architectural libraries of early-nineteenth-century America. Whitfield may well have seen Town’s New Haven residence as well as the Richard Alsop House in Middletown, both displaying the taut, square-pillared corner porticoes like those he later constructed at Gaineswood. In fact, the layout of the formal spaces at the Alsop House anticipates the conceptual arrangement Whitfield used for his own ceremonial suite of public spaces: a lateral main doorway (at Gaineswood the door is entered from a porte-cochere) opens into a transverse hallway containing the main stair, with a large drawing room to the left, and a dining room and library to the right. Gaineswood’s arrangement is more fully developed than that at the Alsop House, incorporating a pair of smaller reception rooms as well, but the essential similarity is unmistakable.

The projecting Doric-order portico that distinguishes Gaineswood’s main front was probably added to an already existing colonnade in the late 1850s. About the same time, a tiara-like open observatory was constructed atop the main roof, allegedly by young Bryan Watkins Whitfield just home from the University of North Carolina. Whitfield’s second marriage in 1857 was the occasion for the last major addition to the house: the low east wing whose facade forms a semicircular bay window wrapped by fluted Doric pillars. This, the so-called “mistresses’s chamber,” was connected via a short hall to the master’s bedroom in the northeast corner of the main block.

To shape and turn the neoclassical columns used both outside and extensively inside, and to handle the multiple carpentry needs of his building enterprise, Whitfield trained his own enslaved craftsmen, who were put to work in purpose-built sheds erected on the grounds of the plantation. As the house took shape, their labor was supplemented by that of artisan plasterers, painters, and glaziers, both enslaved and free.

However, much of the intricate bas-relief ornamentation used freely throughout the house—Grecian-inspired acanthus leaves, palmettes, fretwork, and foliated rinceaux—may have come from elsewhere. Marble mantels for Gaineswood were shipped from Philadelphia, and the decoration for cornices and coffered ceilings apparently were ordered from manufacturer Charles Frederick Bielefeld in London, whose patented papier-mâché architectural ornamentation dominated the field on both sides of the Atlantic by the 1850s. The lavish architectural decor of the formal spaces and two main bedchambers makes all the more stark their contrast with the plain, low-ceilinged upstairs bedrooms presumably for children, domestics, and even guests. These seem almost to have been grouped wherever they would fit around the evolving common areas below.

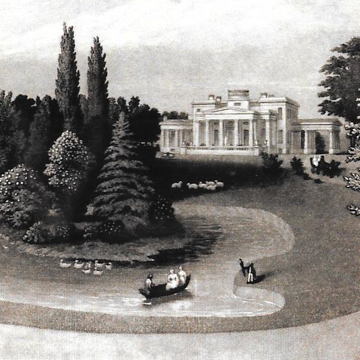

About 1860, Whitfield commissioned John Sartain of Philadelphia to prepare an engraving of Gaineswood. The setting is somewhat idealized after the Victorian manner, but depicts the house as seen looking east—much as it stands today except for the absence of the enclosed parterres fronting both the north and south elevations. Below the house is a small artificial lake, complete with boaters, surrounding a tiny island (of many anecdotes about Gaineswood, one is that the lake was dug by hand and fed by an artesian well). To the left of the mansion is shown the extant neoclassical gazebo designed by Whitfield after the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, a popular icon of Greek Revival movement. Not pictured is the main gate to the estate which, with the adjacent porter’s lodge, then stood northwest of the house facing the east-west road to Uniontown, the forerunner of what would become in the 1920s U.S. 80 (today, the route of the highway runs much further south). While Gaineswood was under construction, Whitfield also lent his architectural expertise to friends and community projects. He engineered and supervised the construction of a mile-long drainage canal from his plantation lands to the Tombigbee River.

With 250 enslaved people at Gaineswood, plus additional plantation lands in Mississippi, Whitfield was heavily invested in the southern economic system when the Civil War erupted in the spring of 1861. Any further development he had planned for the house and grounds was suspended, while emancipation and the general economic devastation following the end of the war in 1865 left Whitfield’s fortunes greatly diminished. Whitfield died three years later, at age sixty-nine. His descendants continued to own Gaineswood well into the twentieth century before it passed into other hands. Meanwhile, the town of Demopolis grew toward the southwest, consuming ever more of the original plantation acreage. Shortly before World War I, a public school claimed part of the landscaped grounds, including the site of the lake, the main gateway, and the keepers lodge. The entrance to the mansion was then moved to the west, facing the north-south Jefferson Road, later designated U.S. 43. Over a two-year period between 1934 and 1936, extensive documentation efforts by the Historic American Buildings Survey produced extensive measured drawings of the house and grounds, along with over sixty photographs.

Reduced to six acres by the 1960s, Gaineswood, long revered as the very embodiment of mythic Old South imagery, was purchased in 1966 by the State of Alabama and placed under the management of the Department of Conservation. It was opened as a house museum, and in 1971 transferred to the newly created Alabama Historical Commission. An extensive refurbishing effort in the early 1970s included removal of a later kitchen wing, which had superseded a long antebellum service wing whose outlines can still be discerned just east of the house. Intermittent restoration campaigns have since followed, addressing both the main structure and extant dependencies. Particularly noteworthy among the latter is a two-room servants’ dwelling, a rustic footnote to the mansion itself. Galleried and raised over a high brick cellar, it would have quartered some of the household domestics.

Today, Gaineswood remains a historic house museum open to the public.

References

Alabama Members, National League of American Pen Women. Historic Homes of Alabama and their Traditions. Birmingham, AL: Birmingham Publishing Company, 1935.

Gamble, Robert S. The Alabama Catalog – Historic American Buildings Survey: A Guide to the Early Architecture of the State. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1986.

Hamlin, Talbot. Greek Revival Architecture in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1944.

Hammond, Ralph. Ante-Bellum Mansions of Alabama. New York: Architectural Book Publishing Company, 1951.

Kennedy, Roger G. Greek Revival America.New York: Stewart Tabori and Chang, 1989.

Lane, Mills B., et al. Architecture of the Old South: Mississippi – Alabama.New York: Abbeville Press, 1989.

Whitfield, Jesse G. Gaineswood and other Memories.Demopolis: privately published, 1938.

Whitfield-Foscue Family Papers and Whitfield-McRory Family Papers (microfilm). Special Collections, Ralph B. Draughon Library, Auburn University, Alabama.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.