You are here

Navajo Nation Council Chamber

The Navajo Nation Council Chamber is a major Public Works Administration (PWA) project and the principal monument of the so-called “Indian New Deal.”

Designed and constructed between 1934 and 1935, the Council Chamber is a tangible symbol of New Deal efforts to end federal assimilation policy, which forcibly attempted to bring Native Americans into mainstream American society by extinguishing their cultures and traditions and breaking up tribal communities, leaving many tribes economically isolated with no commerce and little industry. This was especially true for the Navajos (Diné), whose history included the tragic “Long Walk” beginning in 1864, the forced removal of 8,000 tribal members from their land and imprisonment at Bosque Redondo in New Mexico. In 1868, after years of internment, the government and the Navajos signed a treaty that granted the tribe permission to return to its land, established a reservation, and provided livestock for subsistence as a pastoral society. Today encompassing portions of northeastern Arizona, southeastern Utah, and northwestern New Mexico, the Navajo Reservation comprises the largest area of land retained by a tribe in the United States.

By the early decades of the twentieth century, overgrazing of the tribe’s livestock was causing widespread soil erosion on reservation lands. In response, the federal government imposed stock reductions, which may have lessened the environmental threat but led to an economic and cultural crisis for the tribe. This, in turn, prompted John Collier, Commissioner of Indian Affairs from 1933 to 1945, to develop an Indian New Deal to strengthen tribal culture and self-rule, using the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, as his legislative underpinning. Collier saw the Navajo situation as ideal for Indian New Deal policies and used the reservation as a test bed for pilot projects. The Navajos did not share Collier’s vision for Native Americans: they blamed him for the stock reductions and voted against the IRA. Nevertheless, the Indian New Deal brought economic relief for the tribe through PWA-funded projects that created jobs. The latter were part of the Indian Emergency Conservation Work (IECW) program, an offshoot of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which employed 4,000 Native Americans in Arizona.

Collier’s reform agenda included the PWA-funded overhaul of the building portfolio of the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA). He characterized existing OIA buildings as a collection of nondescript Victorian-era structures devoid of architectural feeling, which he attributed to a lack of comprehensive planning and fluctuating budgets dependent on congressional appropriations. For the first time, PWA funding enabled the OIA to carefully design its structures, including hospitals, community day schools, employee residences, dormitories, gymnasiums, auditoriums, and other buildings both on and off the reservation. Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, who was in charge of the PWA, selected Mayers, Murray and Phillip of New York (Bertram Goodhue’s successor firm), to design OIA buildings in the Southwest. Collier directed the firm to consider five points in the design of the new buildings: the prevailing architecture in the vicinity; the surrounding landscape; the availability of native building materials; simplicity of design while meeting functional requirements; and maximizing opportunity for Native American construction labor. The program was premised on the idea that that studying “Indian forms of architecture” would produce buildings that were more contextual than merely employing obvious decorative motifs. Unfortunately, this goal was not achieved in the new OIA buildings. Instead of drawing from each tribe’s architectural traditions, the OIA employed a one-size-fits-all solution for its buildings throughout the region: the Pueblo Revival style, a romanticized mixture of Spanish Colonial and Pueblo architecture. Thus, though its agenda was cultural authenticity, the program’s actual legacy was often the imposition of culturally alien buildings.

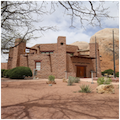

The new tribal capital complex at Window Rock, Arizona, was the centerpiece of the New Deal building program on the Navajo Reservation. Located on the eastern edge of the reservation near the Arizona-New Mexico border, Window Rock is a Navajo sacred site situated amidst immense red sandstone formations, including an impressive natural stone bridge that gives place its name. Between 1934 and 1938, the OIA developed this sparsely populated area into the largest complex of PWA buildings on the reservation, employing a crew of 550 predominantly Navajo workers to construct more than 50 buildings. In addition to the Council Chamber, these included offices for the consolidated Navajo Central Agency and employee housing. Similarly to OIA and PWA buildings throughout the region, these Pueblo Revival structures are built of local materials (here, red sandstone) with rectilinear massing and simple detailing. In keeping with its status as the focal point of the tribal headquarters complex, the Council Chamber occupies a particularly scenic position a few hundred yards south of the natural stone bridge. It stands directly to the west of the Administration Building; an axial alignment that reminded the Navajo of their ties to the federal government. The Council Chamber itself was intended to symbolize tribal self-government and inspire pride in Navajo cultural heritage. The Council Chamber is unique among Indian New Deal buildings in the region because it adapted the tribe’s actual traditional building form, rather than simply applying a Pueblo Revival facade onto a standardized plan.

Externally, the Council Chamber resembles a monumental hogan, albeit one with incongruous Pueblo Revival details. To localize the Pueblo Revival style and harmonize the building with its natural surroundings, the architects substituted local Dakota sandstone for plastered adobe as the primary building material. In plan, the building is octagonal and incorporates traditional Navajo ceremonial features including an east-facing main entrance (so those exiting the building might obtain power and blessing from the rising sun) and a windowless north wall (to prevent bad spirits from entering). The building has heavy massing, consisting of two flat-roofed tiers supported by large radiating ponderosa pine vigas that extend through the massive stone buttresses that project from each of the eight corners. The latter rise more than ten feet above the flat parapet of the one-story primary block. Above, a recessed, half-story clerestory rises ten feet above the parapet. The vigas, which Navajo laborers harvested from the nearby Chuska Mountains, form a network of cantilevers supporting the roof. Pueblo Revival details include exposed wooden lintels and canales (water spouts). Navajo artist Charles K. Shirley carved the wood panels framing the main entrance with scenes depicting The Livelihood and Religious Rites of the Navajo Indians, while an anonymous Navajo stonemason inserted two bas-relief carvings of horse and cow heads in the stonework above the entry.

The interior consists of a single large room lit by eight large clerestory windows, which functions as the council chamber. Its dominant feature is the exposed wood roof structural system that extends through the clerestory walls to the exterior. Steel posts at each corner of the octagon support the clerestory level and separate the main floor from a raised gallery. Navajo artist Gerald L. Nailor (known in Navajo as Toh-Yah, “Walking by a River”), a graduate of the famed art program at the Santa Fe Indian School, painted The History and Progress of the Navajo Nation on the walls of the chamber, an eight scene mural cycle depicting key events in the tribe’s history. The murals were part of the original plans for the building but were not completed until 1943 due to a lack of funds.

Designated a National Historic Landmark in 2004, the Navajo Nation Council Chamber has served continuously as the seat of the tribe’s governmental activities and legislative sessions since its completion. In the 1940s, a one-story sandstone addition was built along the western elevation of the original building. This structure matches the materials and construction of the original building and houses restrooms. Later alterations were less sympathetic, including those on either side of the earlier bathroom addition: wood frame and stucco spaces for mechanical systems and meetings. The Council Chamber’s surroundings have evolved as well, with the addition of new buildings on the formerly undeveloped areas to the north and south. Despite these changes, the building and its immediate environs retain much of their original character, particularly the strong connection between the Council Chamber and its natural setting.

References

Brown, C.W., and R. Stanley Brown. Public Buildings: A Survey of Architecture of Projects Constructed by Federal and Other Government Bodies Between the Years 1933 and 1939 with the Assistance of the Public Works Administration. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1939.

Burt, Sarah, “Navajo Nation Council Chamber,” Apache County, Arizona. National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, 2002. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Collier, John. “Indian Buildings in the Southwest.” American Architect and Architecture150 (June 1937): 34-40.

Collier, John, and Mary Heaton Vorse. “The First Tribal Capital.” Indians at Work: A News Sheet for Indians and the Indian Service1, no. 24 (August 1, 1934): 5-6.

Krinsky, Carol Herselle. Contemporary Native American Architecture: Cultural Regeneration and Creativity. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Leibowitz, Rachel. “Million Dollar Playhouse: The Office of Indian Affairs and the Pueblo Revival in the Navajo Capital.” Buildings & Landscapes15 (2008): 11-42.

Parman, Donald L. Navajos and the New Deal. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976.

Philp, Kenneth R. John Collier’s Crusade for Indian Reform. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1977.

Threinen, Ellen. Navajos and the BIA: A Study of Government Buildings on the Navajo Reservation. Window Rock, AZ: Bureau of Indian Affairs Navajo Area Office, 1981.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.