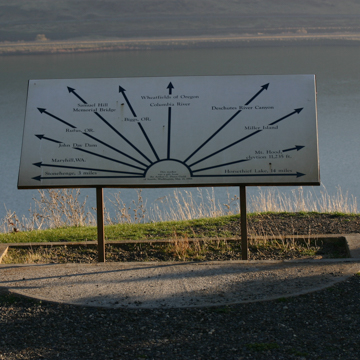

Among the oddest locations for a cultural, social, and artistic complex in the United States, Maryhill sits perched on a lonely bluff 800 feet above the Columbia River, gazing toward Oregon. The complex was developed on a massive, 5,300-acre site by Samuel Hill, a railroad magnate and semi-successful businessman with a zeal for roads, monuments, and international travel. Its isolated location—some 60 miles from the nearest semi-populated city in Washington, in a mostly arid region of the state—has ensured its preservation to some degree. Mostly free from development pressures, Maryhill ambles on, attracting a steady stream of curious visitors for more than a century.

The overall development’s signature piece is the Maryhill Museum of Art, a reinforced concrete, Neoclassical mansion-turned-museum. The far-flung complex also includes the Maryhill Loops Road, ten miles of experimental asphalt paving engineered by Samual C. Lancaster and built in 1911 as the state’s first automobile roadway, and Stonehenge, a full-scale, concrete replica of the assumed final stage of the original version built on England’s Salisbury Plain. The Washington version of Stonehenge, however, was completed in 1929 as a memorial for World War I Klickitat County veterans—the first World War I memorial in the nation. Both the Maryhill Loops Road and Stonehenge are located approximately five miles from the museum, to the northeast and east, respectively.

Perhaps more than anything else, the complex reveals the interests and eccentricities of early-twentieth-century industrialist Samuel Hill. Born in 1857 to Quaker parents in North Carolina, Hill moved with his family to Minneapolis after the Civil War. He later attended Haverford College and Harvard University, returning to Minneapolis where he formed a law practice and later became part of James J. Hill’s (no relation) Great Northern Railroad after winning several lawsuits against the railroad and impressing James J. Hill. In 1888, Hill married James J. Hill’s daughter Mary and moved to Seattle in advance of the railroad’s completion, investing in public utilities in Seattle and later in Portland, Oregon.

In 1905, Hill purchased approximately 7,000 acres of land near what was the tiny town of Columbus on the north bank of the Columbia River that he renamed “Maryhill” after his wife and their daughter. Although branded by Hill as a pristine area for farming “where the rain and the sunshine meet,” in reality the low rainfall and the windy, cold winters offered little for prospective farmers. Hill nonetheless attempted to create a planned Quaker community of farmers, and by 1909 Maryhill boasted two paved streets, a store, a post office, worker housing, a dam for irrigation (now the McCarty Pond), a weather station, a stable, a blacksmith, and a garage. He also began building his experimental roads—ten miles in total. Hill was unable to attract settlers, however, and by 1915 he stopped attempting to sell plots and decided to turn the area into a cattle ranch.

One year earlier, in 1914, construction began on Hill’s two-and-a-half-story Neoclassical mansion. It was designed by the Washington, D.C. architectural partnership of Hornblower and Marshall, which had already established a national reputation with designs for Washington, D.C.’s National History Museum and Baltimore’s U.S. Customs House, in addition to Hill’s own mansion in Seattle. At Maryhill, Hill directed the architects to design the reinforced concrete mansion at one end of his 7,000-acre property as a grand space for entertaining politicians, business associates, European royalty, and others Hill had met from his extensive domestic and international travels. Hill’s choice of concrete for both of his houses, an unusual choice for residential construction at the time, reflected his affinity for concrete as a paving and building material, and suggested his desire to experiment with new materials and technologies. To this end, Hornblower and Marshall included long automobile approach ramps on either side of the Maryhill mansion and a parking lot for Hill’s much-loved automobiles.

Indeed, Hill believed in the power of the automobile and good roads to bring prosperity—at least to all those who could afford a car. But roads could not be built fast enough for Hill; his own experimental loop road notwithstanding, even a road on the north bank of the Columbia River to connect his planned residence and ailing town to the existing road network could not be constructed at the time. This lack of access, financial troubles with his Portland Home Telephone Company, and the entry of the United States into World War I compelled Hill to stop work on his grand mansion. This left little more than a shell devoid of plumbing, furnishings, and fixtures—a situation that largely remained until the house’s conversion to a museum in 1940.

Today, the Maryhill grounds are included as part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, and the nearby William and Catherine Dickson Sculpture Park has been added to the museum’s collection. Despite its isolated location, the museum draws approximately 40,000 visitors per year.

References

Becker, Paula. “Altar Stone of Stonehenge Replica Built to Memorialize World War I Soldiers is Dedicated at Maryhill on July 4, 1918.” Essay 7809. HistoryLink.org: The Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History, June 14, 2006. Accessed July 3, 2017. www.historylink.org.

Campbell, Robert, “Maryhill Museum of Fine Art,” Klickitat County, Washington. National Register of Historic Places Inventory–Nomination Form, 1974. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington D.C.

Tuhy, John E. Sam Hill: The Prince of Castle Nowhere. Portland, OR: Timber Press, 1983.

Wilma, David. “Hill, Samuel (1857-1931).” Essay 5072. HistoryLink.org: The Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History, April 6, 2008. Accessed July 3, 2017. www.historylink.org.

Wilma, David. “Maryhill Museum of Art.” Essay 5084. HistoryLink.org: The Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History, January 21, 2003. Accessed July 3, 2017. www.historylink.org.