You are here

Alphabet Houses

The Manhattan Project, which produced the plutonium incorporated into deadly weapons of war in the early 1940s, also produced an instant city in the high desert of southeastern Washington along the banks of the Columbia River. To construct the world’s first nuclear reactors and plutonium processing plants, thousands of construction workers, engineers, support staff, and their families came from all over the country to what had been the sleepy farming towns of Hanford, White Bluffs, and Richland, and transformed the area almost overnight. Today, traces of these older towns have all but been subsumed within the enormous tracts of land set aside for the Hanford Nuclear Reservation and the modern-day city of Richland, yet the legacy of the city remains intimately tied to the once highly classified project that would eventually mark the end of World War II.

That legacy remains visible in the massive B Reactor and scattered buildings remaining on the vast Hanford Reservation, but perhaps most significantly in what was planned as an egalitarian community for the more permanent employees of the project: the Hanford Engineering Works (HEW) Village. There, the employees lived, shopped, raised families, and enjoyed their version of the American dream in a planned development whose broad, curvilinear, tree-lined streets, transportation, infrastructure, parks, play lots, and houses with lawns extended nineteenth-century picturesque planning and New Deal–era community ideals. The plans simultaneously foreshadowed the automobile-centric sprawling suburbs that characterized the edges of much of postwar urban America.

Before the Manhattan Project came to transform the region, the three small agricultural towns of Hanford, White Bluffs, and Richland were already established along the banks of the Columbia River, not far from the older town of Pasco and across the river from the growing Kennewick community. A wide variety of fruits and vegetables grew on the irrigated landscape, but the towns were small. In February 1943, the 1,500 residents of these three towns were given just days or weeks to vacate their property, which was seized by the federal government at substandard prices. Most of the buildings in the towns of Hanford and White Bluffs were razed to make way for the reactors and attendant facilities, and the DuPont Company oversaw the construction of temporary barracks, mess halls, offices, and recreational facilities needed to support the massive influx of temporary construction workers who came to the Hanford site beginning in spring 1943.

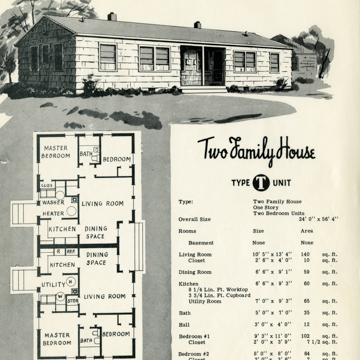

Under contract with the E.I. Du Pont de Nemours and Company (DuPont), Spokane-based architect Gustav Albin Pehrson planned and oversaw the development of an entire community consisting of hundreds of single- and multi-family dwellings. These edifices (together with three prefabricated house plans not designed by Pehrson) were up-to-date in their materials, manufacturing, and speed of construction, but most were designed with a vague nod to tradition, drawing upon Dutch Colonial or Colonial Revival prototypes. The neighborhood plans, too, drew elements from the recent past: New Deal community planning was evident in the parks, schools, and commercial structures as well as different housing types for mixed-income families. As a different letter of the alphabet was used to demarcate the different stock plans for each of the houses, the dwellings earned the moniker “Alphabet Houses” or “Letter” houses.

Swedish-born Pehrson, who had previously worked for the Spokane firm of Cutter and Malmgren before he was hired to design the HEW Village, was beset by the demands of planning the community on a tight schedule: he had to provide plans for the first house type, a duplex, within a week and the entire architectural plans and specifications for the village design in two-and-a-half months. His staff of three quickly grew to over 350 people.

Pehrson’s plans reflected the desire of DuPont for quality and conservative housing for its employees and the thrifty approach required by the Manhattan Project officials. In this way Pehrson’s designs drew from the allegedly democratic attitudes of earlier New Deal community planning, where resettlement efforts for disenfranchised urban and rural residents resulted in planned communities with a centralized commercial core and residences based around a single industry. Yet many of these resettlement projects failed to create cohesive communities as residents struggled under an imposed bureaucracy and insufficient funding. Aiding the planning of Hanford was the military presence, war material, and funding priority of the Manhattan Project, as well as a shared belief amongst high-level government officials that the project was necessary to win the war.

Neighborhoods surrounded a central commercial and entertainment core, and schools, stores, parks, and churches were located within walking distance of one another. Streets were contoured to the low hills and laid out in a curvilinear pattern, existing shade trees were preserved, and houses were angled to the street to provide privacy and to permit crosswinds in the hot summers. The neighborhoods were also provided with “car compounds”—communal parking for each street rather than individual driveways (although many homeowners, over time, incorporated driveways and garages in their building lots). All lots were provided with space for yards, for Pehrson believed that each family needed private space to recreate. Yet he also believed the yards needed to be small enough for a working family to maintain.

Pehrson provided twenty-two floor plans for the Alphabet Houses, each plan named with a different letter, each letter with additional configurations (such as Q1, Q2, etc.), and each built with the same materials and construction methods. Eight of these designs were constructed during wartime, and twelve were added after the war. Housing types ranged from single-story, two-bedroom ranch houses to four-bedroom, two-story houses. Higher quality materials were used regardless of the intended occupant: frames of Douglas fir (harvested from the 1933 Tillamook burn in Oregon) were placed on concrete foundations, while basements, double-hung windows, and hardwood floors were standard. On-site mills, shops, and concrete plants allowed for speedy, low-cost, and uniform construction. Most of the houses were designed to resemble the Dutch or Colonial Revival, but they were minimally embellished.

Construction of the Alphabet Houses began late in April 1943 with the first unit completed three months later. Given wartime demands and an increasing need for engineers and management, construction proceeded quickly under intense pressure until early 1945. Construction was not fast enough to satisfy Manhattan Project planners, however, and they soon shipped in 1,800 partially furnished one-, two-, and three-bedroom prefabricated housing units to supplement the overall project. These units, installed on wooden piers and intended for blue collar or junior employees, were built by the Prefabrication Engineering Corporation of Portland, Oregon, and based on similar wartime housing designs produced for the Tennessee Valley Authority in Knoxville. The prefabricated houses were erected initially with flat roofs that were susceptible to severe damage in heavy winds, so they were later replaced with gabled roofs. Pehrson contended that these prefabricated units, designated U and V, lacked “traditional form or architectural character,” and he considered their placement problematic: they were built in a repetitious, grid-like pattern in the western section of the village away from the river. The prefabricated houses also created class distinctions among residents due to their largely blue-collar occupants and their segregation away from the other neighborhoods, yet Pehrson was nonetheless compelled to incorporate the prefabricated units into his overall plans.

The federal government owned all the houses, and residents could not make additions or changes without government approval. This arrangement remained effective in the immediate postwar years, although the government transferred management to the Atomic Energy Commission. Pehrson remained on the government payroll until 1951, eventually overseeing the planning and construction of a city of 20,000 residents. In the late 1950s, the government began moving towards the privatization of Richland. It relinquished ownership and began offering the houses at reasonable rates, providing current residents the right to first refusal before putting them on the housing market. Few houses today remain in their original condition, but the historic character of Richland’s neighborhoods remains rooted in the wartime-planned community.

References

Carter, Barb. Home Blown: The History of the Homes of Richland. Richland, WA, 1993.

Fetterolf, Gary, and Alyssa Reil. “Richland’s Alphabet Houses.” Reach Stories. Accessed July 21, 2016. http://reachstories.org/.

Hales, Peter Bacon. Atomic Spaces: Living on the Manhattan Project. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Harvey, David. History of the Hanford Site, 1943–1990. Richland, WA: Pacific Northwest National Laboratories, 2000.

Schiessl, Joseph, “Gold Coast Historic District,” Benton County, Washington. National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form, 2005. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.