Built astride the Upper Columbia River between flood-carved cliffs of volcanic basalt, the Grand Coulee Dam is the largest producer of hydroelectric power in the United States. The American Society of Civil Engineers named the dam one of the country’s seven modern engineering wonders in honor of the project’s innovations, but its greatest achievement lay in its size. One of the world’s heaviest concrete structures, Grand Coulee Dam supports the Columbia Basin Project, the most extensive water reclamation project ever executed in the United States. Managed by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the dam impounds up to 9.4 million acre-feet of water into a 151-mile reservoir, Franklin D. Roosevelt Lake. The hydroelectric power produced by the dam, which has a total generating capacity of 6,809 megawatts, is harnessed to pump over 814 billion gallons annually through a network of more than 2,000 miles of canals, irrigating an area of more than 670,000 acres.

1933 marked the commencement of numerous New Deal-sponsored infrastructure projects, all of them serving multiple purposes, requiring lengthy land negotiations and involving significant design and construction challenges, including the Hoover Dam (1931–1936) and the Shasta Dam (1938–1945). Grand Coulee was no different, and it also shared their architectural aesthetic, with stripped-down Art Deco detailing that expressed the mood of the Depression era and reflected the stylistic impulses of the federal relief projects sponsored by the Public Works Administration (PWA) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). At Grand Coulee, the monumental concrete forms embodied a powerful vision of an efficient and technologically advanced nation in command of the world’s most modern infrastructure.

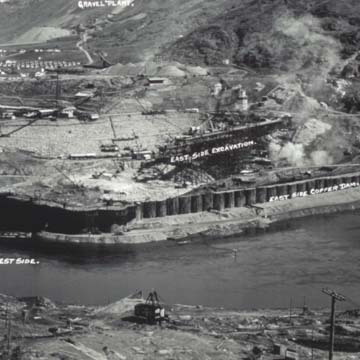

In the early 1930s, engineers from the Bureau of Reclamation debated two design questions that would determine the overall size and form of Grand Coulee. First, should the dam be constructed of multiple arches, in the so-called “structural tradition,” or should it be built as a gravity dam in the “massive tradition,” relying on its weight to hold back the water? Second, should the dam be built in one phase or two: should it begin with an initial “low dam” of 290 feet that could produce electricity and then, when funding allowed, raise it to the full 550 feet height that was needed to support irrigation? Although fiscal constraints suggested proceeding with a low, multiple-arch design, engineers working under the leadership of Chief Design Engineer John L. Savage recommended a low-gravity construction. This decision was driven in part by concerns about safely raising the arched dam in a second phase of construction, but it was equally influenced by the agency’s growing predilection for massive forms.

In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved expenditure of $63 million on the low-gravity design. Initially reluctant to commit the required funds, Roosevelt lent his support to the “high dam” design after visiting the project site in 1934, and viewing the construction that was already underway. In August 1935, Congress approved the additional $7 million needed to implement the entire Columbia Basin Project.

For nearly two decades, agronomists and land managers had considered placing a dam on the Upper Columbia River to use as a source of water to support increased agricultural settlement of the dry Columbia Plateau in central Washington State. The region was promising for large-scale agricultural investment due to its relatively long growing season, its pockets of fertile loess soils, and its strategic location in relation to railroads, highways, and the port cities of Seattle, Portland, and Vancouver. Moreover its unique terrain of dry channels and coulees suggested that it would be conducive to irrigation infrastructure—conduits sculpted by Ice Age floods would carry water again, this time to boost economic prosperity.

By the Great Depression, though the few dryland farmers eking out a living from the parched landscape had moved on, they were followed by small-town merchants and professionals whose livelihoods were likewise tied to agricultural profit. Unsurprisingly, settlements along the banks of the river enjoyed comparatively better conditions, due to the proximity of water, and these included a number of small fruit-growing towns. Prosperity was no guarantee of preservation and most of the riverside communities above the dam would be destroyed by the Grand Coulee’s construction, several of them flooded by 100 feet or more. Even more tragic was the destruction of the ancestral salmon fishing grounds of the Colville and Spokane tribes. Indeed, the loss to the region’s indigenous inhabitants was devastating: the river constituted the cultural, spiritual, and economic life of the tribes, and when it vanished it took away crucial collecting and food foraging sites, locations of sacred significance, and the Kettle Falls fishery—an ancient gathering place for tribes from as far away as the Pacific Coast and the Great Plains. Once the two sides of the dam met in 1938, the Upper Columbia was forever blocked to salmon.

Downstream, by contrast, new towns emerged seemingly overnight as the Bureau of Reclamation built places like Coulee Dam, Mason City, and Grand Coulee to house a workforce of 8,000 men, all under the direction of Construction Engineer Frank A. Banks. Even before the U.S. entered World War II, the pressure of military preparedness accelerated the pace of the dam’s construction in order to provide electricity for wartime industries in the Pacific Northwest. The dam’s generators, located in two power plants flanking the spillway, each the height of a 13-story building, came on line for the first time in March 1941. Their output would eventually support plutonium production at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation on the Lower Columbia River; this plutonium was used in the first atomic bomb.

After the war the rugged Columbia Plateau was parceled into 160-acre farms and sold to private citizens, mainly veterans and their families who grew grain, alfalfa, potatoes, sugar beets, corn, mint, and other crops. To receive a reclamation parcel, farmers had to assume a portion of the project’s construction costs, with individual fees based on the farm’s income and amortized over several decades. While the Bureau of Reclamation received revenue from the sale of land and electricity, it touted this potential recouping of construction costs as a particular triumph of the Columbia Basin project.

In 1966, irrigation and power generation capacity at Grand Coulee increased twofold with the construction of a third power plant at the dam. Modernist architect Marcel Breuer designed the new structure, a commission that reflected the Kennedy administration’s renewed focus on design excellence in federal projects. Heralded as a masterwork of modern architecture, Breuer’s third power plant is an essay in concrete form and light. The third plant parallels the river, mediating between the muscular basalt cliffs and the austere, engineered expanse of the dam and its first two plants. Breuer’s heavy, low-slung massing evokes the dam’s gravity design, while his faceted and textured facade exploits the play of sunlight and crisp shadows typical of the arid Columbia Plateau. Breuer also designed the visitor center perched at the foot of the dam, which echoes the shape of a generator rotor.

Although the reclamation project ultimately fell short of its projected capacity of one million acres, the ecological changes it incited were dramatic and far-reaching. These included the transformation of sagebrush steppe into irrigated, fertilized farmland, the loss of habitat for 350 species of wildlife, and the sudden appearance of more than 600 miles of shoreline in the middle of the desert.

The project’s constellation of more than 100 new reservoirs—particularly its primary impoundment at Lake Roosevelt—was identified from the outset as a prime recreational resource for the region. Because these bodies of water were created by the government, the shoreline was federally owned and made accessible to the public. Boating, fishing, and other water-based activities were actively encouraged, reflecting a management philosophy that would be formalized in 1964 by the development of an entirely new type of national park: the national recreation area. Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area—originally called Coulee Dam National Recreation Area— is one of eighteen such units managed by the National Park Service. Nine of these are associated with manmade reservoirs, reflecting the formative legacy of twentieth-century integrated river basin development in the United States.

References

Billington, David P., Donald C. Jackson, and Martin V. Melosi, The History of Large Federal Dams: Planning, Design, and Construction. Produced for the Bureau of Reclamation, Denver, CO, 2005.

Bureau of Reclamation. The Story of the Columbia Basin Project. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1964.

Bureau of Reclamation. “Grand Coulee Dam” and “Columbia Basin Project.” Accessed February 16, 2015. www.usbr.gov.

McKay, Kathryn L., and Nancy F. Renk, Currents and Undercurrents: An Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area. Produced for the National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area, 2002.

Pitzer, Paul C. Grand Coulee: Harnessing a Dream. Pullman, WA: Washington State University Press, 1994.

Roise, Charlene. “Powerhouse: Marcel Breuer at Grand Coulee.” Docomomo US. September 16, 2014. docomomo-us.org.