Jarrell Plantation is a mid-nineteenth-century cotton plantation owned by a single family for almost a century and a half. Its significance lies in the complex’s preservation of vernacular residential forms, which document constructional techniques and materials use in the mid-nineteenth- to early-twentieth-century outbuildings that are extant here. In addition to providing sawn lumber for their own construction use, the Jarrells provided labor and materials for nearby public buildings and a bridge. Their plantation buildings give evidence of the continuity of both farm and local industrial/mill use of the land on this middle Georgia site.

This area of Georgia was opened to homesteaders in 1805 and by the 1830s, native Indian tribes—in this region was the Hitchiti of the Muscogee (Creek) Confederacy—had become victims of the government’s Indian Removal Act and were forced to move to reservations west of the Mississippi River. Pioneer white settlers, including Blake and Zilpha Jarrell, who moved their family and two enslaved persons here from North Carolina in 1820, began to develop working plantations. Blake and Zilpha’s son, John Fitz Jarrell, along with his wife Elizabeth and their seven children (there would soon be twelve children in all), developed Jarrell Plantation.

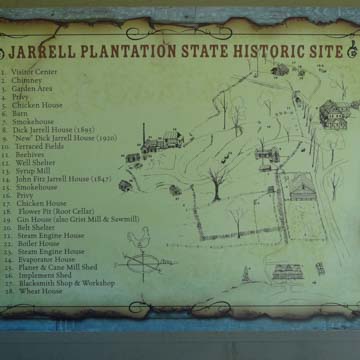

Around 1847, John Jarrell built a house of virgin heart pine from trees felled on the farm that were floated downriver to a saw mill for cutting into planks, and which were then hauled back to the farm site to build the farmhouse and outbuildings. On the front porch of the 1847 house, a traveler’s or “honeymoon” room provided a bedroom for the local teacher, for older children, or for the occasional traveler. The large room at the front of the house contains the only remaining fireplace and, in the tradition of the multipurpose “hall” of earlier house forms, served as the master bedroom, parlor, nursery, sewing room, and office. Straps for a quilting frame hung from the ceiling. The back porch, with its huntboard (tall sideboard), served as a dining room. Adjacent to the dining room was a bedroom converted in the 1890s to a post office and store, the latter selling flour, matches, soda, soap, kerosene, starch, and candy to the hundred or so families who farmed the nearby fields. Of the plantation’s outbuildings, those still extant are an 1870 smokehouse (the only extant log structure on the plantation), a chicken house, a privy, a cow shed, and a flower pit, as well as a circa 1880 kitchen addition on the main house.

By 1850, John Jarrell owned 19 enslaved persons who managed livestock (cows, hogs, sheep, oxen, horses, and mules) on the plantation’s 840 acres. Farm production included cotton, wheat, Irish potatoes, yams, peas, pork, beef, wool, honey, syrup, and ginned cotton. By the time of the Civil War (with land valued at $5,280—$2,840 in livestock and 42 enslaved persons valued at $37,800), Jarrell was in the upper third of the state’s wealthiest planters. Federal troops under William T. Sherman passed through Jarrell Plantation in 1864, stealing livestock and food, and burning the plantation’s first gin house. It was replaced by John, but by the time of his death in 1884, the reduced estate, run by seven farmhands, was worth only about $2,743. By the end of century, many of the farmhands had abandoned the plantation and the earlier slave houses deteriorated and disappeared; only the ruin of one is preserved today.

An interesting structure down the hill to the east of the 1847 house is a 45-foot-deep well shelter (circa 1870) and a stone chimney for a syrup furnace (circa 1850). The latter contained two 68-gallon kettles used for cooking sugarcane syrup. When salt became scarce during the Civil War, John began an annual trip to Savannah, hauling the kettles by wagon to the coast in order to boil seawater to make salt for curing meat. He thus produced enough salt for his own family and to sell to neighbors.

In 1864 John married a Confederate widow (Nancy Ann James) whose son, Benjamin Richard “Dick” Jarrell, returned to the farm in 1895. He built a second dwelling with lumber milled onsite and with handmade nails, and erected several outbuildings (the smokehouse, chicken house, and privy) as well as a large barn with three mule stalls and ten cow and ox stalls. (This group of buildings are those sited closest to today’s visitor center at the historic site.) Down the hill to the south, Dick developed a small industrial ensemble of structures, including a cotton gin with a saw mill underneath. Dick obtained contracts to build a school, church, other houses, and a bridge in the immediate locale.

In 1916–1917, the mill complex was enlarged with a boiler house, large and small engine houses, and syrup evaporator house. The 12-horsepower Schofield steam engine was Dick’s first engine, permanently mounted with the small engine house built around it. Belts accessed other machines through two openings, and an overhead steam pipe was connected to the boiler. The larger 30-horsepower Talbot steam engine in the main engine house is still functional. A 40-horsepower Schofield engine, also in the boiler house, powered both engines by means of an inspirator that drew water from a spring, which was then heated by wood fire, with steam carried to the engines by metal pipes. Also dating from 1916 is the cane planar mill shed (to crush sugar cane for juice to make syrup, and for planning wood or cutting tongue-and-groove flooring). The evaporator house allowed an efficient means of producing syrup, as opposed to the earlier kettle method employed in the syrup furnace near the well.

Slightly earlier in date is the 1912–1913 dirt-floored workshop, half of which was a blacksmith shop (to make or repair wagon wheel rims, horse and mule shoes, harness chains, and the like), and the other half of which was a carpenter’s shed for harness repair, lathe work, etc. The most recent building in the complex is the 1945 farm implement shed containing a Case thresher (used to separate wheat seeds form the stalk), a reaper-binder (to cut wheat and tie it into bundles), a log cart, a sulky (two wheel horse cart), and other stored equipment.

After World War I, when Dick Jarrell’s sons returned from the war, the Jarrells built a 5,000-square-foot, 10-room, 2-story house recalling in style larger southern residences of the 1850s, and constructed of native heart pine (as with other houses on the Jarrell plantation). Here Dick’s son, Willie Jarrell, lived until his death in 1984; Willie’s nephew still resides in the “1920 house,” operating a bed-and-breakfast inn. Ten years before Willie died, the Jarrell family donated the plantation and its various surviving furnishings, artifacts, and pieces of equipment to the State of Georgia to be preserved as a state historic site.

References

“Jarrell Plantation.” Georgia Department of Natural Resources, State Parks and Historic Sites. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://gastateparks.org/.