You are here

Fort Sisseton

Fort Sisseton, located in northeastern South Dakota, was built by the federal government in 1864 as Fort Wadsworth. It was meant to assist settlers in areas east of the James River, to provide protection for miners headed to Montana and Idaho following the Dakota War of 1862, and to suppress fighting among local Native American tribes. The 35-acre site was chosen because it contained an ample supply of lime and clay for brick-making, a nearby lake for drinking water, and a thick stand of trees for timber and fuel. The fort was protected by a perimeter of earthen breastworks topped with stacked logs that created an 8-foot barrier. The first buildings were constructed of logs harvested from area trees, but were later replaced with more permanent stone and brick structures. At the height of activity, the fort housed between 120 and 200 infantrymen.

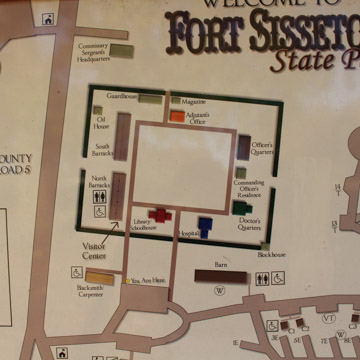

Since there was another Fort Wadsworth in New York, the fort was renamed in 1876 for the nearby Sisseton band of Sioux, who provided scouts to the fort. During the late 1880s, when the area had already been settled, post commanders recommended closing the facility. The property was transferred in April 1889 to the Department of the Interior, and following the removal of all supplies and equipment, was closed that June. The state eventually acquired the site. In the 1930s, the Works Progress Administration undertook restoration of fort’s buildings. The fort was designated a State Historic Park in 1959. Today there are fifteen structures remaining at the site, with the main buildings arranged around a square parade ground.

The north and south barracks, both constructed of fieldstone, were 45 x 182–foot structures designed to house 150 men. By the 1930s, only the exterior walls remained and both were reconstructed. The north barracks now houses the visitors’ center. In the fort's later years the south barracks served as a storage area for commissary supplies; its interior walls were not rebuilt during reconstruction. A stone and brick magazine was one of the few structures in near-original condition by the 1930s.

The commanding officer’s residence is a two-story brick building with later kitchens and sheds built on the rear; these were not replaced during reconstruction. The doctor’s quarters also had a later addition but the wooden lean-to has not been rebuilt. West of this residence are depressions in the ground marking the hospital toilets and the death house, where bodies were stored when the ground was frozen. The one-and-a-half-story, rectangular hospital building, constructed of brick, was expanded to 33 feet wide and 60 feet long during the fort’s later years. One of the last facilities erected at the fort was the library/schoolhouse, a one-story brick structure that later served as a telegraph office and is now a park ranger’s residence. Other fort structures include a stone oil house, a two-room brick guardhouse, the one-story brick adjutant’s office, 28 x 28–foot log blockhouses, and carpenter’s and blacksmith’s shops.

The few structures built outside of the breastworks include the commissary sergeant’s quarters and the quartermaster sergeant’s quarters, about 25 feet to the west. About 100 feet southwest of these buildings was a 3-room root cellar that stored produce grown in the fort’s three gardens. The 35 x 219–foot stone stable, which contains 78 stalls, originally had a gable roof but was redesigned to the present gambrel roof during the WPA restoration.

Today, Fort Sisseton offers seasonal guided tours, interpretive displays, and a gift shop. It is also the site of an annual festival featuring period entertainment and activities.

References

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.