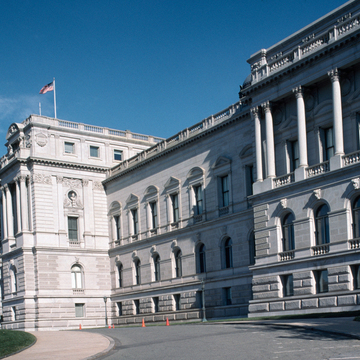

The Library of Congress was the first building in Washington to express fully the tenets of the Beaux-Arts system of architecture. Situated centrally on its own landscaped block and having a complex entry sequence integral to its design, the library exemplifies the nineteenth-century French planning thesis

The probable source of inspiration for Smithmeyer and Pelz was Charles Garnier's Paris Opera House (1861–1875). The major features of its main facade were slightly altered by the library's architects for their central pavilion. Many features were derived from the famous Parisian model—an arcaded entry enriched by allegorical figures, double giant columns that integrate single-bay flanking pavilions to the rest of the facade, bull's-eye windows that frame busts of great men, an attic story with segmental pediments containing emblematic sculpture. In addition, interior separation of the building's symbolic purpose (represented by the sculpture, mosaics, and frescoes of the grand staircases and promenade) from its actual functions (focused on the reading room) is similar to the division of the actual theater at the Paris Opera from its public promenades. The Library of Congress glorifies American contributions to world knowledge in the same hierarchical manner as the Paris Opera glorifies France's contributions to the performing arts.

Secondary attention was given to the corner pavilions on the exterior, which originally contained separate reading rooms for special collections, such as rare books, maps, prints, and manuscripts. Thirty-three keystones representing the races of humankind are located in arches above the entrance-story windows on all four sides of the building. Modeled by William Boyd and Henry Jackson Ellicott from evidence compiled by Otis T. Mason of the Smithsonian's department of ethnology, the heads are grouped according to their racial affinities. The biased presentation shows the European (located to the left of the main entrance) as a portrait of Beethoven, while many of the nonwhite races are depicted as savages. Although it was common on Victorian buildings to trace the development of plant and animal species, the Library of Congress may be the first attempt on a monumental public building to embody humankind's variety through racial models.

As the library's major architectural forms prepare the visitor for the location and size of important internal rooms, and its multilevel entrance staircase suggests the spatial progression to be encountered within, its program of exterior sculpture establishes the

The sculptural program of the main entrance establishes the specificity within universality that characterizes the iconographical program of the entire library. The six spandrel figures above the triple doors were carved in granite by Bella Lyon Pratt and represent literature at the north door, science in the center, and the arts on the south. The reliefs on the bronze doors set within arched recesses allegorize the development of human communication from the storyteller to the printed page. Oral Tradition is linked with figures modeled by Olin Warner representing Imagination and Memory on the north doors. Frederick MacMonnies's Art of Printing, illustrated by Humanities and Intellect on the center doors, is associated with the development of science. Warner and Herbert Adams's Art of Writing is allied with Research and Truth on the south doors. Two stories above, nine busts placed in front of bull's-eye windows portray Benjamin Franklin, who is given pride of place, flanked by Europeans, the writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and the historian Thomas Macaulay. Americans Nathaniel Hawthorne and Washington Irving occupy the next positions; Ralph Waldo Emerson and Sir Walter Scott are in the pavilions. The busts on the sides of the pavilions, Dante on the south and Demosthenes on the north, represent the traditions from which modern literature evolved.

Beyond the entrance is a lavishly decorated and intricately developed series of spaces that spreads vertically as well as horizontally. The vestibule is presided over by Minervas of War and Peace who raise torches of learning. Passing into the main hall one encounters the dramatic richness of the multilayered and multileveled stairhall flooded with light from windows on three stories and a flat stained-glass ceiling. Signs of the zodiac revolving around the sun are inlaid in bronze on the marble floor, the whole symbolic of the universe. Children above the fountains on the sides personify the four continents, a traditional method of succinctly representing the human portion of the universe. These figures were sculpted by Philip Martiny as were the children intertwined with garlands that line the staircases; they symbolize various intellectual and manual occupations. Bronze female torchbearers (electric lighting fixtures) preside over the hall. Names of famous writers are inscribed in gold in the ceiling vaults.

Throughout both levels of the main hall, painted lunettes and mosaics symbolically depict numerous branches of knowledge. Names of their renowned practitioners, ancient and modern, European and American, are linked to these images. Pertinent quotations (supplied by Harvard president Charles Eliot) are included on the mezzanine as the system intensifies. Those disciplines dependent on creative thinking are located just beneath Vedder's mosaic. Wisdom apparently is the culmination of the entire process, but closer inspection reveals two staircases that lead to a public balcony overlooking the main reading room. The octagonal reading room was specified by Librarian of Congress Ainsworth Spofford to accommodate a new system of organizing books (and hence knowledge) under eight hierarchical headings. Stacks on each wall of the reading room were to contain the reference books for each branch of learning identified by the allegorical figures atop each of the clusters of Corinthian columns marking the divisions. Appropriate quotations in cartouches above the statues continue the Beaux-Arts system of linking the visual arts with the written word to explicate the meaning of a building. Two statues of great men representative of each discipline stand on the upper balcony flanking the allegorical figures. Religion (Theodore Baur, sculptor) is represented by Moses and Saint Paul; Commerce (John Flanagan, sculptor) by Columbus and Robert Fulton; History (Daniel Chester French, sculptor) by Herodotus and Edward Gibbon; Art (François M. L. Tonetti-Dozzi after sketches by Augustus Saint-Gaudens) by Michelangelo and Beethoven; Philosophy (Bella Lyon Pratt, sculptor) by Plato and Sir Francis Bacon; Poetry (John Quincy Adams Ward, sculptor) by Homer and Shakespeare; Law (Paul Wayland Bartlett, sculptor) by Solon and James Kent; and Science (John Donoghue, sculptor) by Isaac Newton and Joseph Henry. Of the

Encircling the oculus of the dome are allegorical paintings by Edwin Blashfield that depict historical contributions to civilization. In chronological order: Egypt gave written records; Judea, religion; Greece, philosophy; Rome, administration; Islam, physics; the Middle Ages, modern languages; Italy, the fine arts; Germany, printing; Spain, discovery; England, literature; France, emancipation; and America, science.

Creating a systematic order out of the multiplicity of world knowledge is a fundamental function of libraries, but also it was a preoccupation of the nineteenth century. The craze for classification demonstrated here continues the eighteenth-century Linnaean practice of identifying plants and animals according to a binomial system. In no other Washington building is the visible expression of iconography so intricately and inextricably connected with its architectural organization. The Library of Congress is a literal demonstration of the Neoplatonic belief that knowledge may be embodied in structure. The building is not a passive container of learning but an active participant in it.

Such profuse and colorful decoration, however, tends to distract one from some architectural dissonances. For instance, the double Corinthian columns forming the upper court of the stairhall do not turn the corners but are layered in the direction of the main axis. As a result the arcades and lunettes are of different widths. There is a conflict between the mosaic lunette on the west window wall in the poets' corridor (located in the south hall, entrance level) and the surrounding entablature, as the interior does not match the exterior fenestration. Although the Library of Congress has neither the control nor integration of the architecturally greater Boston and New York public libraries, there is a vigor in its overblown character. The iconography is so relentless that it transcends minor architectural infelicities, but it so overwhelms visitors that they need a guide to unravel it as well as a map to identify and locate specific rooms.