You are here

Edith Farnsworth House

Designed in 1946 as a country residence for Edith Farnsworth, the Farnsworth House is the clearest architectural expression of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s vision of “beinahe nichts,” or “almost nothing,” the reduction of elements to their essence.

In late 1945 or early 1946, architect Mies and Dr. Farnsworth were seated together at a Chicago dinner party. Farnsworth, a leading nephrologist, was unmarried and frustrated at the social limits imposed upon a single woman. She had recently purchased some property along the Fox River near Plano, about 60 miles southwest of Chicago, intending to build a country house suited to her personal needs. Over dinner, she suggested to Mies that one of his students might be interested in the job. Whether Mies was impressed by the doctor’s intelligence, or excited by the possibility of implementing his architectural ideas, he agreed to take on the commission himself. By the summer of 1946, the basic plan for the house was complete. In 1947, plans and a model appeared in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, where they inspired curator Philip Johnson to design his own Glass House, in New Canaan, Connecticut. Waiting on an inheritance, Farnsworth could not begin construction until 1949, and Mies spent the intervening years refining his design and developing meticulously considered details for the steel and glass house.

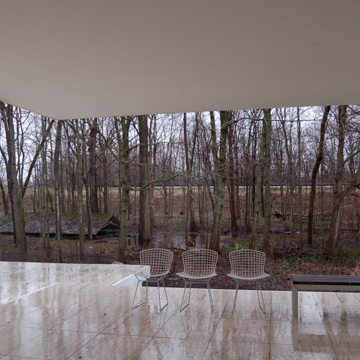

Set along the Fox River, the Farnsworth House’s cantilevered travertine stairs lead to a low terrace, with a second set of steps leading to an upper terrace and the living space, enclosed by floor-to-ceiling glass. Four pairs of steel columns suspend this glazed space above the ground. Travertine pavers flow seamlessly from the terrace into the house, where the main living areas are contained within a single, open room. Two partitions separate the zones of the house: to the north, a primavera-veneered core accommodates the kitchen and bathroom, along with mechanical functions; to the east and set perpendicular to the kitchen core, a teak veneered box serves as a wardrobe.

The white-painted, sandblasted steel frame—with welds sanded away to render attachments invisible—contrasts with its natural setting, becoming an object of Platonic perfection, seemingly more idea than reality. Far from a static, isolated object, the sliding horizontals of the house and terraces reach out and engage their natural setting, offering a contrast to emphasize the rich colors and natural forms of the seasonally changing riparian prairie. Mies served as General Contractor on the project, and his innovative details and iron-willed vision proved costly. Though initially budgeted at $30,000, because construction began just as the Korean War was driving up material costs, the house ultimately cost Farnsworth more than $70,000, a staggering sum at a time when the average single-family house cost less than $10,000. Farnsworth and Mies eventually sued each other regarding the overages, and a painful court case drew national notoriety to the unconventional residence. In the media, their financial dispute became tied up with a larger contemporary perception that modernism represented a foreign attack on traditional American culture.

In the midst of this heated atmosphere, Farnsworth took ownership of the house in 1951. Her memoirs make it clear that living in a famous and transparent structure had decided disadvantages, but Farnsworth used the house as a rural retreat for more than twenty years, suggesting that she ultimately found peace and happiness while dwelling in what is regarded as a modernist masterpiece. It was not all tranquility however; and in the 1960s, Farnsworth found herself protesting the proposed relocation of a Kendall County bridge across the Fox River. Her attempts to block the project were unsuccessful and in 1967, the lights and noise of higher speed traffic intruded upon her retreat.

A few years later, Farnsworth decided to retire to Italy and she began seeking a buyer for her famous country house. Lord Peter Palumbo, a British developer and unabashed admirer of the aging master, purchased it from Farnsworth in 1972. Palumbo and his family visited the house for a few weeks a year, and transformed the property to fit their needs. Inside the house, Palumbo made necessary repairs and minor improvements, adding air conditioning, a stone hearth, and some furniture. Outside of the house, over the course of more than three decades, Palumbo utterly transformed the site. Farnsworth had had only a single wood-framed garage on the property, located near the road and out of site from the house, and she did little to alter the existing landscape. Palumbo, in contrast, commissioned landscape architect Lanning Roper to design a series of broad lawns and intimate landscaped rooms, and placed his collection of outdoor sculpture throughout the site. He expanded the garage to accommodate a bathroom and sauna, and built a swimming pool and tennis court near the garage, still largely invisible from the house. A wood-framed boathouse, set below grade, lies along the Fox River, just west of the house.

While still in the design phase of the project, Mies consulted local farmers about the water table, and he determined that setting the house about five feet above grade would be sufficient to keep the house dry when the river flooded. In 1954, however, the river waters rose higher than five feet, inundating the house, and forensic evidence suggests that the house flooded other times during Farnsworth’s occupancy as well. It was not until 1996 that flooding cause severe damage. Water rose so far above the upper plinth that standing water five feet deep remained in the house for several days. The water shattered one pane of glass and destroyed the veneered core, metal kitchen cabinets, and teak wardrobe. As soon as was possible, Palumbo began an extensive renovation. In 1997, he built a temporary visitor center east of the house and opened up the property for tours. Five years later, Palumbo put the house up for auction. Working in partnership, the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Landmarks Preservation Council of Illinois (now Landmarks Illinois) were able to purchase the modernist icon. The National Trust now owns and operates the house as an historic site. A 2008 flood damaged the core and required extensive repairs to the freestanding teak wardrobe. Given the understanding that upriver development and global warming have permanently increased the frequency of high water events at the Farnsworth House, flooding remains a threat to the site.

References

Blake, Peter. The Master Builders. New York: Knopf, 1960.

Blaser, Werner. Mies van der Rohe Farnsworth House: Weekend House. Basel: Birkhauser, 1999.

Drexler, Arthur, ed. The Mies van der Rohe Archive. Vol. 13. New York: Garland Publishing, 1986.

Friedman, Alice T. Women and the Making of the Modern House. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

Johnson, Philip C. Mies van der Rohe. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1978.

“Mies van der Rohe: Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois, 1945-50.” Global Architecture Detail 1 (1976). Special issue.

Milnarik, Elizabeth, “Edith Farnsworth House,” Plano County, Illinois. Historic American Buildings Survey (IL-1105), 2010. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Schultze, Franz. Mies van der Rohe: A Critical Biography. Rev. ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Schultze, Franz, ed. Mies van der Rohe: Critical Essays. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1989.

Vandenburg, Maritz, Farnsworth House: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. London: Phaidon Press, 2003.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.