You are here

Thornhill

House, setting, and story seamlessly come together to make Thornhill a quintessential plantation house, complete with pillared portico. From the veranda, a commanding view of rolling fields and woodlands lacks only crimson-coated foxhunters and baying hounds. And since Thornhill’s beginnings it has remained owned by the same family—a great rarity in twenty-first-century Alabama.

Thornhill’s progenitor was James Innes Thornton (1800–1877), who lies buried in the family cemetery on the brow of a hill a short distance from the mansion he built. Like so many émigré planters of the Deep South, Thornton was a Virginian, born at the Fall Hill plantation near Fredericksburg. He studied at Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) and then headed south to Alabama, first to Huntsville in the Tennessee Valley, where he joined his brother in the practice of law. Soon he became involved in Alabama politics, and in 1824 was elected Secretary of State. At the same time, he began developing the alluvial plantation lands he had acquired in west-central Alabama, some fifty miles south of Tuscaloosa, which, in 1826, had been designated the state capital. Genteel rural life proved a stronger pull than politics, however, and after five consecutive two-year terms as part of the state’s executive junta, Thornton decided to withdraw from the political arena and devote himself entirely to planting. This event would seem to corroborate longstanding family tradition that dates construction of the house to 1833.

Thornhill’s basic design is conventional: the two-story, hipped-roof form (rooted in Georgian Britain) displayed by countless eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century American houses with some pretention to “style.” It is the same core form that occurs at Thornton’s still-extant family residence, Fall Hill, back in Virginia, though rendered there in brick instead of wood. Physical evidence suggests that Thornhill originally may have had a central two-tiered portico, which was replaced some time later by the monumental hexastyle Ionic colonnade fronting the house today. It is conceivable that the same renovation campaign extended to interior trim and mantelpieces. A gracefully curving stair ascending from the back of the main hallway recalls comparable stairways in Tuscaloosa, a similarity that hardly seems coincidental. Two large rooms on either side of the hall, plus two more pairs and a bisecting hallway directly above, compose the original eight-room residence. Formal rooms to the left of the main hall, now parlor and dining room, are connected by large paneled sliding doors. As customary in the South, food was prepared in a separate structure to the rear. An undated early sketch plan of the house shows what appears to be a semidetached rear wing (possibly for dining) connected to the main house by means of a small porch and covered way. The same sketch places the kitchen itself nearly fifty feet away from the house to the northeast.

Thornhill is among several houses in Alabama that some scholars have attributed, without documentary proof, to William Nichols, architect for the Tuscaloosa statehouse as well as the original campus of the University of Alabama. Nichols was indeed active in the area until at least 1835, when he assumed the role of architect for the proposed new Mississippi State Capitol in Jackson. As to Thornhill’s portico, architectural historian Clay Lancaster has speculated it to be the work of local builder David Rinehart Anthony of Eutaw. At least half a dozen other houses in Greene County, four of them still standing, have similar Ionic colonnades, most notably nearby Rosemount, now inaccessible to the public.

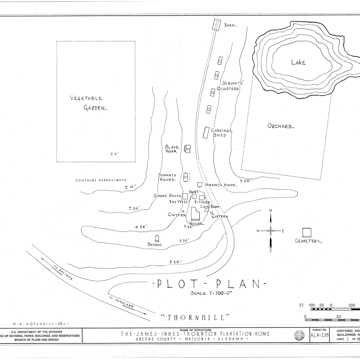

When the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) documented Thornhill in the mid-1930s, a small brood of dependent structures still clustered about the “big house”: a kitchen and cook’s house, dovecote, smokehouse, and “lock room” (presumably, a secured storage house), two peak-roofed well houses, and two subterranean brick cisterns. Only the cisterns remain today. HABS photos also show the rudimentary two-story porch and bathroom wing that had by then been added across the rear of the house. The same set of images also show the plantation bell that summoned workers to and from the fields, set into a rough framework of cedar posts.

Farther away, along a narrow ridge running behind the plantation house, likewise still stood in the 1930s a carriage house, barn, and a half-dozen hewn-log slave dwellings. (During the antebellum period, quarters for other plantation workers—there were more than 150 bondsmen at Thornhill in 1860—were probably elsewhere on the 2,000-acre estate.) These structures have since disappeared.

Still remaining, however, is a one-room plantation schoolhouse partway down the knoll from where the house sits and overlooking the entrance lane that winds up from the main road. The school may have been built to accommodate the several school-age children of Harry Innes Thornton (1848–1900), who, in 1877, succeeded his father as master of Thornhill. It could, however, have been built earlier. Tradition holds that youngsters from surrounding plantations were educated here along with the Thornton household. In 2012, the school was adaptively refurbished as a guesthouse.

Changes to the main residence since then have been minimal, aimed toward sensitively adapting it to contemporary living without compromising its original character either inside or out. During the mid-1990s a sunroom previously added to the east side of the house, as well as a rear service wing, were redesigned and reconstructed so as to better complement the original structure.

References

Alabama Members, National League of American Pen Women. Historic Homes of Alabama and their Traditions. Birmingham, AL: Birmingham Publishing Company, 1935.

Gamble, Robert. Alabama Catalog–Historic American Buildings Survey: A Guide to the Early Architecture of the State. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1987.

Glass, Mary Morgan. A Goodly Heritage: Memories of Greene County. Clarksville, TN: Josten’s and the Greene County Historical Society, 1979.

Hammond, Ralph. Ante-bellum Mansions of Alabama. New York: Architectural Book Publishing Company, 1951.

Lancaster, Clay. Eutaw: The Builders and Architecture of an Ante-Bellum Southern Town. Clarksville, TN: Josten’s and the Greene County Historical Society, 1979.

Thornton Family Papers. Collection of Brock Jones, Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.