You are here

Kenworthy Hall

After amassing a fortune as a cotton buyer in the brisk Mobile market of the mid-1800s, Edward Kenworthy Carlisle commissioned the prestigious New York firm of Richard Upjohn and Company to design his family’s country residence. The Carlisles selected a locale in the interior of the state near the town of Marion, not far from his widowed mother’s plantation and adjoining that of his planter brother-in-law, Leonidas Walthall. A few years earlier, Walthall had also employed Upjohn to design his residence, Forest Hall (a towered villa as well, but of frame construction and now long destroyed). Kenworthy Hall was begun in 1858 and effectively completed on the eve of the Civil War. It stands today as the only known example of Upjohn’s residential work surviving south of the Potomac.

A firm whose domestic architecture is typically associated with the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states, Upjohn and Company here confronted the challenge of adapting their usual domestic format to the requirements of a southern climate and a plantation way of life. Carlisle’s stylistic choice, not to mention the sheer scale and ambition of his building enterprise, must have startled his neighbors in what was still a quasi-frontier rural landscape, where even the better houses were usually simple frame dwellings that rarely aspired to more than a wooden portico with neoclassical trappings.

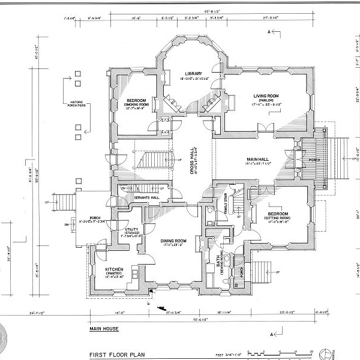

Superficially, Kenworthy Hall is related to a domestic template that Upjohn used in his design for the Edward King House in Newport of the 1840s: an Italian villa (albeit a very sober one) rendered in russet American brick and brownstone. In Alabama, in observance of longstanding southern custom, Upjohn provided a separate brick kitchen house complete with breezeway, along with a long, spacious back veranda overlooking the rear service area so important to the rural southern household. Unlike in the King house and most of his other northern designs, Upjohn also introduced a breezy through-hall in his layout for Kenworthy—a critical climate-control feature in large southern houses of the period.

For its place and time, the interior arrangement is singularly complex; rooms and apartments of various shapes and sizes play off the axial hallway. The circulation pattern clearly separates private family spaces—concentrated to the left of the main hall—from the more public areas. Both a private family stair and a sequestered servants’ stair augment the heavily banistered ceremonial staircase in the main hall, which rises to a landing before branching and reversing course to continue its gradual ascent to the second floor. There are other appointments to match: built-in corner bookcases of polished oak, a wine closet, paneled doors with faux finishes of oak and mahogany, marble mantelpieces, and decoratively plastered ceilings. The massive loadbearing brick walls throughout the house, all expertly constructed, incorporate a two-inch dead space that serves as a moisture barrier.

Among tall trees in its rustic hilltop setting, Kenworthy Hall is an unexpected sight along a country highway. Its asymmetrical front of advancing and recessed bays is dominated by a ponderous, four-story brick tower from which juts a canopied balcony. Beneath broad overhanging eaves, the window openings are variously rounded and segmentally arched and are emphasized by brownstone sills and hoodmolds. Belt courses, also of brownstone, enliven expanses of wall faced with pressed brick. The present plain wooden entrance porch replaces a more elaborate one that was removed more than a century ago. Gone, too, is the arcuated back veranda that was still present during the mid-1930s when the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) photographed the house.

After a period of abandonment in the 1950s, during which vandals stole marble mantles and shattered a large stained glass window illuminating the main stair landing, Kenworthy Hall was reoccupied in 1960. Still a private residence, it has had numerous owners and intermittent periods of hopeful restoration. In 1997, a second HABS recording initiative, spearheaded by the Alabama Historical Commission, documented the house and grounds. Kenworthy was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2004. Among its original surviving dependencies are the two-room brick kitchen, a domed brick cistern, and a frame carriage house.

References

Cooper, Chip, Robert Gamble, and, Harry Knopke. Silent in the Land. Tuscaloosa: CKM Press, 1993.

Gamble, Robert. Alabama Catalog: Historic American Buildings Survey: A Guide to the Early Architecture of the State, 1810–1930. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1986.

Gamble, Robert, and Robert Mellown. “Kenworthy Hall,” Perry County, Alabama. National Historic Landmark Nomination, 2003. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.