Before the coming of the railroad, Alabama’s system of navigable rivers was a vital link in its agricultural economy—the means by which thousands of bales of cotton annually reached the port of Mobile and the Gulf of Mexico. Gainesville, perched on a wooded bluff overlooking the Tombigbee River, was a key inland shipping point in this trade, as well as a center of local commerce. Similar cotton shipping points, like Cahaba and Claiborne on the Alabama River, have passed into history. And so, for that matter, has most of the nineteenth-century townscape of Gainesville. But enough remains in terms of architecture and the traces of early street patterns to gain some physical and spatial sense of a community whose antebellum significance can scarcely be imagined today.

In the beginning, Gainesville was also a jumping-off place for scores of hopeful speculators and planters who flocked here eager to invest in the fertile lands wrested from the Chickasaws by the United States in the 1831 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. Joseph Baldwin, a young Virginia attorney who, in 1837, hung out his shingle in Gainesville, has colorfully captured the spirit of this restless, rowdy, optimistic period in his Flush Times of Alabama and Mississippi, a humorous classic of early American frontier literature.

Gainesville’s founder, Moses Lewis, was himself an enterprising middle-aged New Englander lured southward by the promise of the Gulf states—the “Old Southwest” as it would later come to be called. In 1832 he purchased a strategically located tract of land on the Tombigbee, convenient to nearby cotton-producing prairies and sited along a major stagecoach route connecting the upper Tombigbee country with the lower Mississippi Valley. He then had his purchase surveyed into an ambitious grid of some forty square blocks, with four lots to a block. In the long run, this would prove to be optimistic overreach. But over the following decade, Gainesville’s population surged (as high as 3,000 or 4,000, some sources insist) before settling back to roughly 1,500 residents by 1850.

On a commanding hilltop that overlooked the river and steamboat landing on one side and a long block of wooden stores and shops on the other, rose the American Hotel, galleried and topped by a lookout and belfry. Of the commercial structures from this period there remains only the Bank of Gainesville (c. 1835–1840), a diminutive building faced with pediment and pilasters in the manner of the high Greek Revival. Moved to Tuscaloosa in the 1960s, then returned to Gainesville by a local benefactor in the 1990s, the bank now occupies its original location adjoining the triangular town park (a “green” in New England) with its nineteenth-century bandstand. There was also an academy, a Masonic lodge, and four churches—the first being the extant Presbyterian Church (1837), of which Moses Lewis himself was the chief benefactor. Only slightly modified inside today, its large U-shaped gallery was set aside, in part, for enslaved African American worshippers.

To the east lay the main residential area and the substantial residences of the wealthier townspeople, scattered among more modest frame dwellings. From Gainesville’s steamboat landing, neighboring plantations annually sent as many as 6,000 bales of cotton to the wharfs of Mobile for transshipment to the mills of Europe and the Northeast. In return, household commodities and plantation supplies, imported luxuries, and even ice were brought from the Gulf Coast some 350 meandering miles up the Tombigbee. In 1855, the town suffered a devastating fire that claimed more than thirty buildings. But on the eve of the Civil War, Gainesville flourished as one of the three main shipping points (along with Columbus, Mississippi, to the north and Demopolis to the south) on the Tombigbee.

The town’s inland location, away from the main theaters of conflict, turned it into a major Confederate hospital center after 1862. Yet military action did not physically touch Gainesville until the very end when, on May 15, 1865, it witnessed the parole by Union Commanding General Edward R.S. Canby of defeated Confederate forces under General Nathan Bedford Forrest.

In the years that followed, it was not the waning of the plantation economy that spelled Gainesville’s doom as a cotton shipping point. Rather, it was the decline—especially after 1880—of river commerce before faster and ever more convenient rail transportation as the major lines bypassed the town. In 1915 the landmark American Hotel was razed, and in the century since, other landmark structures have disappeared one by one. The widening of State Highway 39 through the town in the early 1980s, coupled with construction of a new bridge over the Tombigbee, measurably altered the historic topography, obliterating the hill where the American Hotel had stood and, with it, a prime archeological site. In 2010 Gainesville’s population was less than 200—a seventh of its population in 1850.

Listed as a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985, Gainesville and its immediate environs still count a score or more of buildings erected between the 1830s and 1880. These include Colgin Hill (circa 1835) on the southern outskirts of town, originally an open-hall, hewn-log dogtrot. Weatherboarded and transformed a few years later into a spacious cottage with a veranda, Colgin Hill architecturally embodies the town’s emergence from the frontier.

On a bluff high above the river, founder Moses Lewis’s house and four other early dwellings survive on Yankee Street—so named, it is said, for the northern-born merchants who made their homes here. In fact, the prim, two-story, hipped roof Lewis House (circa 1835) seems lifted right out of its builder’s native New Hampshire. Inside, there is an exceptionally graceful stairway. And at the rear, a double piazza (now enclosed) once overlooked the Tombigbee and the fertile bottomlands beyond. Lewis’s business office to one side of the house could as easily face onto a New England green.

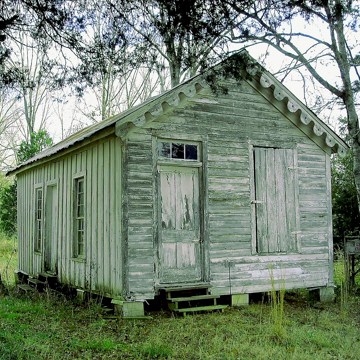

In contrast, the Russell-Turrentine House (circa 1840) at the western end of Yankee Street seems transplanted upriver from Mobile: a “Creole cottage” with a steeply pitched dormered roof extending over its inset, Doric-pillared veranda. A classical architrave frames the unusual doorway, which is actually two separate entrances opening into separate front rooms that could, when desired, become a single open space by opening wide, paneled double doors. The Greek Revival is represented next door to the east in the modest temple-front of the Goodloe-Harrison House and, just beyond, the remodeled and now-abandoned Fall House.

Four other Gainesville residences, all believed to date from the 1840s or the early 1850s, express the versatility of the Greek Revival in its heyday. A well-proportioned Doric portico in miniature frames the doorway of the Ellis House, its formality an unexpected contrast to the functional informality of the rear elevation, with a low service wing of astonishing length.

As a creative departure from the academic norm, however, none of Gainesville’s Greek Revival houses are more arresting than Aduston Hall and the Travis-Harwood House. Architectural companions, they were built by brothers Amos and Enoch Travis, allegedly as summer retreats from their primary residence in Mobile. Sometimes described as “ranch-style Greek Revival,” the houses are long and low, with Doric-pillared verandas sunk between pilastered and pedimented end pavilions. Their nearly identical footprints—a sort of elongated H—are adapted to maximize cross-ventilation during sultry Alabama summers. Who built the two houses is unknown, but their resemblance to a handful of other houses in the area suggests the same hand. A likely candidate could be housewright Hiram Bardwell (1800–1879), one of four Massachusetts-born master carpenters sharing the same surname who worked across mid-nineteenth-century Alabama. For some thirty years or more, Bardwell resided in the county seat of Livingston, ten miles south of Gainesville, and may well be the one to whom can be attributed the serene wooden Doric porticoes seen now and again hereabouts.

Nor can Bardwell’s name be ruled out for the Green G. Mobley House (circa 1845). More orthodox in its rendering of the Greek Revival than Aduston Hall and the Travis-Harwood House, the imposing Mobley House occupies a spacious corner lot behind a handsome brick wall nearly as old as the house itself. It could almost be the princely home of a Nantucket whaling merchant. Indeed, its facade appears to combine elements from two plates appearing in Chester Hills’s The Builders Guide, published in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1834. By the following year, this influential carpenter’s manual was being sold in Mobile’s leading bookstore, and became a mainstay of itinerant builders throughout the Deep South. Directly across the street from the Mobley House, the pedimented double galleries of the Ellis-Waddell House capture the neoclassical spirit in more rustic form; its four-bay, two-door front hints that it may have originally served some non-residential purpose.

If Gainesville’s earliest builders remain unidentified, the name Edward Kring is everywhere apparent in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Arriving in 1860 as a young “mechanic” from New York State, Kring was effectively the town builder over the next three decades. The Kring carpenter shop, part of the complex out of which he worked, stands today. His own residence, now the Kring-Cate House (circa 1870), exhibits the signature scroll-cut woodwork that he applied to new buildings like the two-story, side-hall Allison-McClelland House (circa 1875) as well as renovated old ones, like the Minniece-Roberts House (circa 1840, 1870).

Kring is also credited with the Methodist Church (1872), as well as St. Alban’s Episcopal Church (1876). Belatedly Greek Revival, the handsome Methodist church was old-fashioned when built but is said to be a smaller replica of the previous church lost to fire. In contrast is the picturesque, Carpenter Gothic St. Alban’s Church. Both structures remain virtually unaltered inside and out, conscientiously maintained by a dwindling number of local churchgoers.

Collectively, Gainesville’s buildings tell a story of socioeconomic rise and decline that has played out repeatedly across the landscape of Alabama. In their diversity, they likewise offer an exceptional opportunity to understand the dynamics of early vernacular building in a single nineteenth-century community.

References

Arrington Collection. Julia Tutwiler Library, University of West Alabama, Livingston, Alabama.

Baldwin, Joseph Glover. The Flush Times of Alabama and Mississippi.New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1854.

Bailey, Michael, “Gainesville Historic District,” Sumter County, Alabama. National Register of Historic Places Inventory–Nomination Form, 1984. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Sulzby, James F. Historic Alabama Hotels and Resorts. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1960.