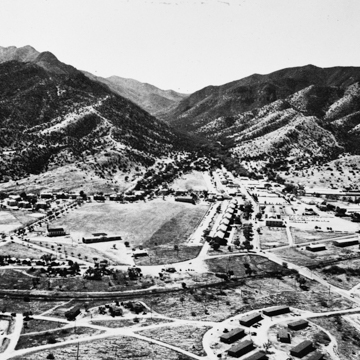

Located 15 miles north of the Mexican border, Fort Huachuca spans 76,000 high-desert acres at the base of an eponymous mountain range. Between 1849 and 1886 nearly 70 U.S. Army posts were established in the Arizona Territory in response to conflicts with Native Americans; Fort Huachuca is the only one to survive into the twenty-first century as an active military installation. The fort is best known as the celebrated cavalry command of the Buffalo Soldiers, the African American Tenth Cavalry Regiment, and as the home of two all-Black infantry divisions until the Army was desegregated in 1948.

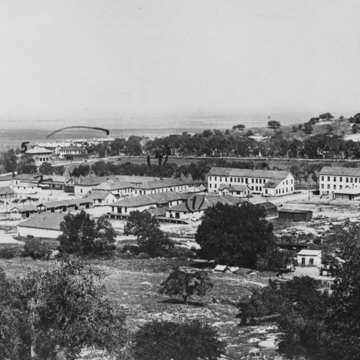

In 1877 Captain Samuel Marmaduke Whitside established Camp Huachuca as a small, temporary outpost near the mouth of Huachuca Canyon, using the base as a strategic center for campaigns against the Chiricahua Apaches until Geronimo’s final capitulation in 1886. During the Apache Wars, the base also functioned as an experimental station for a heliograph system that used sun-reflecting, tripod-mounted mirrors to send messages 30 miles away. Early shelters included field tents and a thatch-roofed, adobe-walled bakery. In 1880, a field hospital was erected; now known as the Carleton House and used as officers’ quarters, the single-story stucco dwelling has a raised basement, 21.5-inch-thick adobe walls, and a gabled roof.

The camp was designated a fort in 1882, which necessitated the first major building campaign. Spanning nine years, this effort resulted in 23 adobe and frame structures in what is now called the “Old Post Area,” the westernmost section of the installation’s 110-acre historic district. These include the single-story, stuccoed adobe administration building; the Pershing House (1884), a stuccoed adobe-and-concrete officer’s residence; the Hazen House (1891), a two-story captains’ duplex; Brayton Hall (1887; remodeled in 1905), a mess hall; and a row of 10 adobe, 1.5-story officers’ quarters (1884). These buff-colored, stuccoed quarters are oriented southwest-northeast along the trapezoidal, grassy parade ground. Across the green are 4 barracks (1883), 2-story wooden-frame buildings painted light green on stone foundations.

The most complex frame building is the Leonard Wood Hall (1885–1887), at the northeast end of the parade, which served as a hospital until 1941: a 2-story central pavilion with a hipped roof is flanked by 1.5-story, gabled wings with monitors, while a veranda spans the entire facade. Other buildings from this era include wood-frame stables, the Bakery (1886), the Guardhouse (1885), the Chapel (1891), and the Quartermaster’s Storehouse (1883). Similar in appearance, the buildings exhibit the Territorial Style, a late-nineteenth-century style that the Army employed across all of its regional installations in that era.

Following truce with the Apaches, Fort Huachuca was used as a training facility for soldiers during the Spanish-American War and Philippines conflict (1899–1902). Because of the fort’s proximity to the Mexican border, it hosted a permanent border patrol during the turbulent years of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) and acted as the logistical staging base for General Pershing’s Punitive Expedition in 1916–1917. The African American Tenth Cavalry Regiment, which had been stationed here intermittently in the last two decades of the nineteenth century, was permanently garrisoned here from 1913 to 1931. The fort’s significance in Black military history is further underscored by the 1916–1917 command of Charles Young, the first African American to achieve the rank of colonel.

The garrisoning of the Tenth Cavalry spurred a second building campaign between 1912 and 1917, most of it concentrated on a secondary parade ground that was extended to the northeast. Here, the Army built 7 frame-and-concrete enlisted men’s barracks (1913–1916) as well as 13 officers’ duplexes arranged in a semicircle. The latter are all 2-story, U-plan buildings covered in beige-painted stucco and capped with gabled roofs. Two-story, screened galleries with shed roofs line the facades. During this period, the Bachelor Officers’ Quarters (1915) and Rodney Hall (1917) were also erected, as were other ancillary structures. After World War I, the Army abandoned many of its outposts along the Mexican border, but retained Fort Huachuca, and building continued there through the 1920s, including the small, utilitarian telegraph office (1919) and detached bungalows for officers.

Fort Huachuca was a cavalry outpost for the first 40 years of its existence, but when the Tenth Cavalry regiment departed in 1931 it became an exclusively infantry installation. Between 1933 and 1942, the fort hosted Arizona’s Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) enrollees, who received basic masonry and carpentry training before being dispatched across the state. Contemporaneously, with the state’s only all-African American CCC camp and funding provided by the Civil Works Administration (CWA) and its successor Works Progress Administration (WPA), a third building campaign was undertaken to modernize the military installation. This work included the Alchesay (or “Million Dollar”) Barracks (1938) along with infrastructural and recreational projects, such as fieldstone culverts, well houses, a reservoir, and fieldstone grandstands for Brock (baseball) Field.

The fort’s building boom expanded at the start of World War II, during which two all-African American infantry divisions – the 92nd and the 93rd –trained here before being deployed to the European and Pacific theaters. The presence of segregated divisions is reflected in Fort Huachuca’s built fabric and evident in the Mountain View Black Officers’ Club (1942) coupled with the Lakeside Officers’ Club (no longer extant) for whites. In 1942, noted African American architect Paul Revere Williams designed a housing project with 125 units for the fort’s Black enlistees. Though best known for his LAX Theme Building (1961), Williams was no stranger to housing, having participated in the design of the 400-unit Pueblo del Rio complex in Los Angeles just prior to his work at Fort Huachuca.

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Williams received an engineering degree from UCLA before apprenticing with local architects Reginald D. Johnson and John C. Austin. He opened his own office in 1922, and by the 1930s, he was designing residences for Hollywood’s stars in exclusive communities like Beverly Hills and Bel Air. Williams was the only western architect President Hoover appointed to the National Memorial Commission, formed in 1929 to design a building “suitable for meetings of patriotic organizations, public ceremonial events, the exhibition of art of inventions, and placing statues and tablets” that would acknowledge contributions of African Americans “to the achievements of America.” This appointment spurred Williams’ work in Washington, D.C., where he eventually opened a satellite office and designed a men’s dormitory for Howard University (1939). Williams was the first African American to become a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects (1957) and his prestige as an architect adds to the significance of Black history at Fort Huachuca.

This heritage is further bolstered by the work of contemporaries like Lew Davis (1910–1979), an Art Project Supervisor for the WPA. Davis established a silkscreen workshop at Fort Huachuca, employing members of the Ninth Service Command, who produced Army recruitment posters featuring Black soldiers. Davis also painted the mural The Founding of Fort Huachuca (1943) for the White Officer’s Mess and a pentaptych mural The Negro in America’s Wars (1944) for the Black Officers’ Mess. This mural was sent to Howard University in 1947 and all five panels remain in the permanent collection of the University’s Gallery of Art.

The fort was briefly deactivated from 1947 until 1951, but was reopened with the onset of the Korean War. In 1954, the Department of Defense chose Fort Huachuca as the site of the U.S. Army Electronic Proving Ground because of the area’s very low radio-frequency pollution. Yet again, the increase in population at the fort created a need for new housing; between 1956 and 1957, the architectural firm of Neutra and Alexander designed a series of modernist residences. The Department of Defense commissioned Neutra’s to design large-scale military housing at such bases as the Mojave Marine Corps Auxiliary Air Station (1955) in California, Idaho’s Mountain Home Air Force Base (1959), and the California Naval Air Station Lemoore (1959–1961).

More than 100 buildings have been added to the active installation since 1957, and the neighboring civilian community of Sierra Vista emerged as a result of this population increase. Since 1967, Fort Huachuca has been the center of the U.S. Army Strategic Communications Command. The historic core of Fort Huachuca was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976. The fort has a historical museum open to the public.

References

Adams, George A. “Fort Huachuca,” Cochise County, Arizona. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1976. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Fisher, Charles J. “Paul R. Williams, Architect (1894-1980).” City of Los Angeles, Department of City Planning, Recommendation Report, Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the Victor Rossetti Residence, Case No.: CHC-2007-5209-HCM.

Goodfellow, Susan, Marjorie Nowick, Chad Blackwell, Dan Hart, and Kathryn Plimpton. “Nationwide Context, Inventory and Heritage Assessment of Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps Resources on Department of Defense Installations.” Prepared for Department of Defense Legacy Resource Program, Project 07-357, July 2009.

Moore, David W., Jr., Justin B. Edgington, and Emily T. Payne. “A Guide to Architecture and Engineering Firms of the Cold War Era.” Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program, Project 09-434. March 2010.

Neutra, Richard J. “Richard and Dion Neutra Papers, 1925-1970.” Online Archive of California, Collection No. 1179. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles, Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library.

Wilkins, Robert L. “A Museum Much Delayed.” The Washington Post, March 23, 2003.