You are here

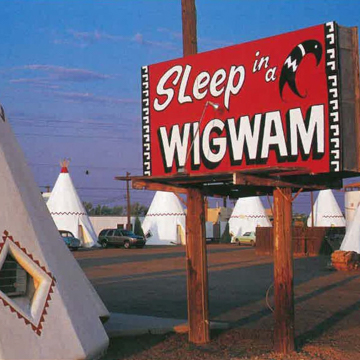

Wigwam Motel

Shortly after the end of World War II, Chester E. Lewis was passing through Cave City, Kentucky, when he encountered a motel with a filling station, lunchroom, and store occupying a village of Indian tipis. Lewis determined to build a similar complex on property he owned fronting West Hopi Drive, as U.S. Highway 66 was known, as it passed through his hometown of Holbrook, Arizona.

In the years immediately after World War II, automobiles were affordable and gasoline was plentiful for the first time in years. As a result, Americans of every stripe took to the highways in increasing numbers, especially on Route 66 from Chicago to Los Angeles. What became the federal highway was part of a nineteenth-century wagon road and later a railroad route, before it was graded and paved for motor vehicular use. Although Route 66 was an important highway for destitute migrants escaping the Dust Bowl in the 1930s, after World War II a new generation of travelers were seeking romantic escapes from everyday life. Increasingly, they were demanding something resembling the comforts of home. Unique roadside accommodations like those Lewis had seen in Kentucky catered to expectations.

Architect/builder/entrepreneur Frank A. Redford opened the original Wigwam Village in 1933 as a filling station and cafe on U.S. Highway 31E in Horse Cave, Kentucky. The main building was a 60-foot-tall steel frame and concrete “wigwam,” whose design, in fact, more closely resembled the transitory tipi shelters of the nomadic Plains Indians than it did the wigwam dwellings of the Eastern Woodlands tribes. It was apparently inspired by the Teepee Barbeque Stand that the well-traveled Redford had seen in Long Beach, California, though he had also encountered actual “teepees” on a South Dakota Sioux reservation.

Redford correctly assumed that his tipi-like structures would appeal to tourists, and by 1936, he had patented his design. In response to customer requests he soon added six cabins, all smaller versions of the original tipi units, along with men’s and women’s restrooms flanking the original cafe, forming what he by then was calling a Wigwam Village. In 1937, Redford opened his Wigwam Village No. 2 in nearby Cave City, on the more rapidly developing “Dixie Highway” (U.S. Highway 31W). The new village boasted 15 guest units arranged in a semicircle around another large “wigwam” housing the gas station, lunchroom, and souvenir store. Two smaller restroom structures flanked the main building. Coordinated staff uniforms, menus, stationery, decor, and souvenirs reinforced the tipi theme.

Conceptually, the Wigwam Villages grew out of the old tourist camp model, appealing to travelers seeking inexpensive and unpretentious overnight accommodations. Redford’s wigwam idea caught on, despite his reticence at promoting them as a chain. Over the next sixteen years, Redford licensed the construction of four more villages and built another himself. Each village was an independent franchise although the individual owners were committed to mutual referrals and shared word-of-mouth advertising. While Redford maintained close association with his franchisees, lack of sole proprietorship undermined the long-term viability of the villages, especially as original owner/entrepreneurs died or sold their properties. Imitation villages also diluted the brand because Redford was loathe to prosecute unlicensed competitors, despite his patent.

Redford sold his Kentucky holdings after World War II and moved to California, building the last official Wigwam Village in San Bernardino. Village No. 7, which Redford operated himself, was sold after his death in 1958. Chester Lewis, meanwhile, had tracked Redford down after his chance encounter with Wigwam Village No. 2 and had arranged to purchase a license and a set of plans. When he returned to Holbrook, Lewis began work on the motor court, doing most of the construction himself, with help from family and friends. His Wigwam Village No. 6 opened on June 1, 1950, the last of the independently owned and operated villages to be completed (Redford’s own No. 7 was actually finished before Lewis’s No. 6). The Holbrook village featured 15 guest “wigwams,” arranged in the shape of the letter C at the perimeter of the rectangular site. The gas pumps, office/store, and restrooms were at the open end of the C, facing the highway. Regularly spaced around a gravel auto court, the guest units alternated with juniper trees, seating areas, and an occasional concrete dinosaur or actual petrified log. Unit No. 6 was the first completed.

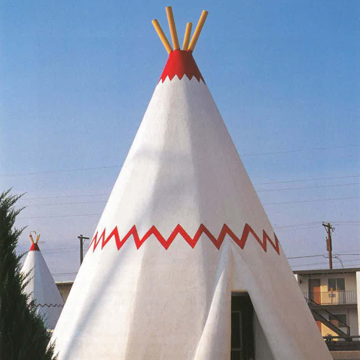

Each identical guest unit stands nearly 25 feet high, not including faux tent poles, with a 20-foot diameter at the base. Built of concrete over a steel frame, all units have 16 sides. Plaster “tent flaps” that appear to fold back on either side of an inset door indicate the entry of each tipi-shaped structure. Every guest unit has a small bathroom containing a sink, toilet, and shower. The original gas heaters and electric lights remain, as do the two 18 x 24–inch windows, positioned for viewing at sitting height. Lewis fabricated the original rustic furnishings himself, out of bark-covered hickory wood.

As specified in Redford’s licensing contract, coin-operated radios were installed in each unit, enabling guests to enjoy a half-hour of music or drama for a dime. At the end of each month, the coins were collected to pay the licensing fee. Redford also supplied molds (for a fee) for making tipi-shaped ashtrays and lamp bases.

In the late 1950s, when Texaco began requiring standardized filling stations, Lewis demolished the original, centrally placed “wigwam,” replacing it with a vaguely Pueblo Revival structure with a canopy over the gas pumps. Though Wigwam Village No. 6 did brisk business throughout the 1950s and 1960s, when I-40 bypassed downtown Holbrook in April 1974, business on old U.S. 66 immediately began to wane. In response, Lewis bought property at the I-40 Holbrook interchanges and licensed newer motels there. He soon closed the Wigwam Village, although he kept the gas pumps open a while longer. For the next dozen years, Village No. 6 sat deserted. After Lewis died in 1986, family members unlocked the doors of the individual wigwams and discovered that little had changed since the 1950s. The original pink color scheme was still in place, as were the rustic hickory stick-and-wicker furnishings. With tourist trade picking up again along “historic” Route 66, the family decided to begin renovating the village. A few units were ready for guests in 1988 and the entire village was refurbished soon after.

Alhough the gas pumps are long gone, the canopy now serves as a porte-cochere for arriving guests. The main building houses a souvenir shop and museum, as well as the office. The flanking restrooms structures are now used for storage. Cable television and refrigerated air conditioning have been added to each unit, in keeping with the tradition of offering “modern” amenities in a rustic setting. In the twenty-first century, the Wigwam Village in Holbrook attracts tourists from across the country and across the globe. As was the case in the 1950s, visitors from as far away as Europe and Japan remain intrigued by the idea of sleeping in a fantastic adaptation of a Plains Indian abode, whether we call it a tent, a tipi, or a “wigwam.”

References

Algeo, Katie. “Indian for a Night: Sleeping with the ‘Other’ at Wigwam Village Tourist Cabins.” Material Culture 41, no. 2. (2009): 1-17.

Patterson, Ann, and Mark Vinson. Landmark Buildings: Arizona’s Architectural Heritage. Phoenix: Arizona Highways, 2004.

Sculle, Keith A. “Frank Redford’s Wigwam Village Chain.” In Roadside America: the Automobile in Design and Culture, edited by Jan Jennings, 125-135. Ames: Iowa State University Press for the Society for Commercial Archeology, 1990.

Witzel, Michael Karl. Route 66 Remembered. Osceola, WI: Motorbooks International, 1996.

“Wigwam Village Motel #6 Holbrook, Arizona.” National Park Service. Accessed June 8, 2015. http://www.nps.gov/.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.