Located in the heart of central Arizona, Prescott is the seat of Yavapai County, and served as the Territorial capital from 1864 to 1867 and again in 1877–1889. The city contains one the oldest and best-preserved groupings of architecture built in the Southwest during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This building stock reflects the New England and Midwestern cultural influences of its early Anglo-American settlers, who largely eschewed the Hispanic and Native American traditions that shaped the architecture of other parts of the state during this period. The Courthouse Plaza Historic District, a roughly 17-acre area of the central business district surrounding the Yavapai County Courthouse and Plaza, is a remarkably intact record of the city’s early civic and commercial architectural development.

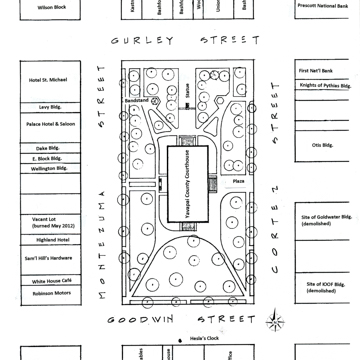

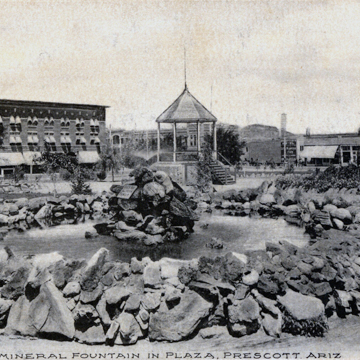

Prescott’s founding coincided with the discovery of gold in the area and with the establishment of the Territory of Arizona in 1863 and of nearby Fort Whipple in 1864. Prescott’s 1864 plat, prepared by Robert Groom and Van C. Smith, followed two practices common to nineteenth-century planning: a grid pattern of wide streets laid out without regard to the topography of the land and two blocks set aside for use as a public park and county courthouse complex. Downtown lots were 25 feet wide and 150 feet deep. The four streets surrounding the Courthouse Plaza were designated for commercial use. By 1865, this area had become the city’s commercial center, and Prescott had emerged as the political and economic center of the region.

Before it was incorporated as a city in 1872, Prescott was a frontier town established amidst the largest ponderosa pine forest in the United States, an area without roads, railroad, infrastructure, or other communities (its population was 676 in 1870). The first choice of building materials was, out of necessity, wood and most early buildings were of log construction. Sawn lumber became available in 1867; brick plants were established by about 1875. The Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railway arrived in 1886, bringing more sophisticated building materials, including redwood lumber, cast-iron storefronts, plate-glass windows, terra-cotta embellishments, and, most importantly, high-quality fired brick.

Buildings were mostly wood frame structures erected on single or conjoined lots with zero setbacks on the front and sides. After an 1890 fire consumed a number of these frame buildings, including businesses and residences, construction tended toward locally made brick or locally quarried stone in an attempt to “fireproof” the new buildings. A decade later, however, there were still numerous wood frame buildings around the plaza, and the established pattern of zero setbacks had continued as well; it would later be codified by the City of Prescott.

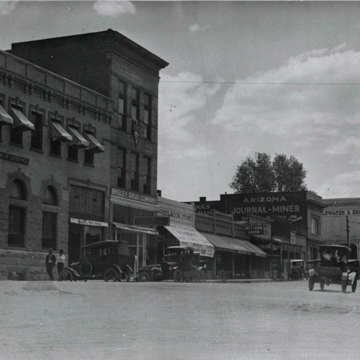

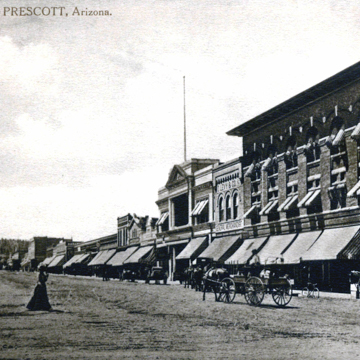

On July 14, 1900, a major fire burned most of downtown to the ground, including a number of the supposedly more fireproof buildings constructed after the 1890 fire. Eight city blocks were devastated, although a few buildings surrounding the Plaza did survive. As was the case in so many other urban areas, this fire significantly changed the architectural face of downtown. Prescott businesses were determined to rebuild, this time in brick, stone, and concrete masonry. Almost all of the construction on the four streets surrounding the Plaza was completed by 1903. With a few exceptions, all of those buildings are extant today. In rebuilding the commercial district, most business and property owners favored traditional styles exhibiting controlled formality, including Beaux-Arts, Georgian Revival, Classical Revival, Romanesque Revival, and Second Renaissance Revival. While these classical interpretations reflected the conservative and mostly midwestern influences of the populace (numbering 3,559 in 1900), the presence in the community of trained architects also exerted a strong influence on the design choices of the time.

There are thirty-six buildings and five vacant lots on the four streets surrounding the Plaza with the Yavapai County Courthouse (1916–1918) as the anchor. The majority of buildings on the plaza have a symmetrical massing and are generally rectangular in plan. The buildings vary in height from one to four stories, with, for the most part, fourteen feet in height for each story, so that the story levels line up from building to building, regardless of a structure’s overall height. Most buildings feature articulated decorative trim with corbelling, dentils, brick banding, pilasters, and ornamental terra-cotta, always reflecting the distinct architectural style of the individual building. As is typical of commercial buildings from this period, these typically exhibit strong horizontal proportions and large plate-glass storefronts.

West Gurley Street, framing the north side of the Plaza, has the most cohesive group of buildings though South Montezuma Street, bordering the west side of the Plaza and known as “Whiskey Row,” has similar continuity of setbacks, but for an open space caused by a May 2012 fire, when one of the buildings on the block burned to the ground. West Goodwin Street, on the south side of the Plaza, has a different character: it contains the oldest building in the district, the City Jail and Firehouse (1890), which sits adjacent to a single-story, Streamline Moderne building from the 1930s and the Beaux-Arts U.S. Post Office and Federal Court (1931–1932). South Cortez Street, marking the Plaza’s east side, also includes the Knights of Pythias Hall (1892), which was among the city’s largest nineteenth-century commercial buildings and one of the few major buildings on the Plaza to survive the 1900 fire. South Cortez Street is divided mid-block by Union Street, which originally provided a direct connection to the “Capital Block;” after Prescott lost its designation as territorial capital, this block was broken up for residential lots.

Prescott has diligently worked to retain its rich architectural heritage despite losing a few buildings to fire, demolition, or excessive remodeling. There has been little new construction since the 1930s, excepting the City Hall of 1961–1962 and the reconstruction of two storefronts around 1970, though plans exist for an infill structure on the now vacant lot on the 100 block of South Montezuma Street, which would restore the solid street wall along Whiskey Row. The Courthouse Plaza Historic District is listed on the National Register of Historic Places for its association with the development of Prescott and as a cohesive grouping of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century commercial architecture.

References

Burgess, Nancy, “North Prescott Townsite,” Yavapai County, Arizona. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 2009. National Park Service, U. S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Burgess, Nancy, and Richard Wiliams. A Photographic Tour of 1916 Prescott, Arizona. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2005.

City of Prescott, and Nancy Burgess, Historic Preservation Specialist. Courthouse Plaza Historic District Properties Survey Final Report.Prescott, Arizona, 1987.

City of Prescott, and Nancy Burgess, Historic Preservation Specialist. A Property Owner’s Guide to Prescott Historic Districts. Prescott, Arizona, 2007.

Garrett. Billy G., ed. The Territorial Architecture of Prescott, Arizona. Prescott, AZ: Yavapai Heritage Foundation, 1978.

Garrett, Billy, and Marjorie H. Wilson, “Prescott Territorial Buildings Multiple Resource Area” Yavapai County, Arizona. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1978. National Park Service, U. S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C.

Ruffner, Melissa. Prescott: A Pictorial History. Prescott, AZ: Primrose Press, 1991.

Sanborn Map Company. 1901, 1910 and 1924 Prescott, Yavapai County, Arizona Maps, amended. New York: Sanborn Company, 1901, 1910, and 1924.

Secord, Paul R., and H. J. Kolva, “Prescott Post Office and Courthouse,” Yavapai County, Arizona. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1984. National Park Service, U. S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C.

Walker, Henry P., and Don Bufkin. Historical Atlas of Arizona, 2nd ed. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986.