You are here

John Ferraro Building

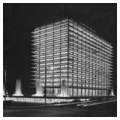

The iconic International Style John Ferraro Building dominates the western end of the civic center in downtown Los Angeles, facing east towards City Hall. Glowing with electric light at night and surrounded by a wide reflecting pool with fountains in the daytime, A. C. Martin and Associates’ architectural masterpiece brilliantly symbolizes the building’s function as the headquarters of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (DWP).

Upon its completion in 1965, this 17-story building became the headquarters for the largest municipal utility in the United States, consolidating more than 3,200 employees into one location. Founded in 1902 to provide water to the growing city of Los Angeles, the DWP opened the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913 with engineer William Mulholland’s famous words, “There it is, take it.” The DWP added electric service in 1916, and by 1939 was the sole provider in the city of Los Angeles.

Placed on a white podium, surrounded by wide reflecting pools contained within a rectangular white basin, this rational, efficient, powerful design stands alone on a city block, distinct from neighboring buildings. Below the cantilevered pools, a subterranean parking garage able to accommodate 2,400 cars provides ample parking for staff, yet allows the building to “float” on top of the hill. These raised reflecting pools surround the building, helping to sustainably cool it. Four lighted fountains flank each side of the building and provide a dramatic reminder of the power of those who control the water in arid Los Angeles. A wide black slate bridge provides access across the pools to the main entrance on Hope Street.

Architects A.C. Martin and Associates cleverly used both light and water as strong design elements. Deeply overhanging white concrete floor plates alternate with smoked glass curtain walls and dark structural steel. In daylight, these walls of windows appear cool and dark, recessed from view, but when the interior electric lights are on at night and the light reflects out onto the white concrete overhangs, the building transforms into a visually stunning spectacle of light. Both day and night, its prominent location on a high point in downtown makes it clearly visible from City Hall, the 101 and 110 freeways, and the surrounding area.

Inside, an elaborate “floating” spiral staircase connects the two-story main lobby with a lower floor, and a circular basin of water emphasizes the bottom of the staircase. Fifteen floors are above street level, with two below. Each floor is approximately one acre in size and organized around a central core containing a bank of elevators, mechanical equipment, restrooms, and stairwells. Upper floors were designed as office space with moveable partitions and drop-down ceilings. On the flat roof, a double-height parapet wall conceals both the rooftop mechanical equipment and a helipad.

The landscape architecture firm of Cornell, Bridgers and Troller designed the landscape. Founded in 1955 by Ralph Cornell, the firm also designed the nearby Los Angeles Music Center, Civic Center Mall (now Grand Park) and City Hall East Mall, as well as the modernist Franklin D. Murphy Sculpture Garden and the Inverted Fountain at University of California, Los Angeles.

Though still known by residents as the DWP Building, in 2000 it was renamed the John Ferraro Office Building in honor of the city’s longest serving councilman. The building received the American Institute of Architects’ Twenty-Five Year Award in 1999 and was declared a Los Angeles Historic Cultural Monument in 2012.

References

“Beauty Plus Utility: A new municipal water and power office complex provides landmark attractiveness for downtown Los Angeles.” American City, March 1966.

Birnbaum, Charles A., FASLA, and Robin Karson. Pioneers of American Landscape Design. New York: McGraw Hill, 2000.

“Construction of the DWP’s General Office Building (GOB).” Water and Power Associates. Accessed September 12, 2018. http://waterandpower.org/.

“Department of Water and Power Building.” Los Angeles Conservancy. Accessed September 12, 2018. www.laconservancy.org/.

De Wit, Wim, and Christopher James Alexander, eds. Overdrive: L.A. Constructs the Future 1940-1990. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2013.

“DWP Building to be Dedicated Today.” Los Angeles Times, June 24, 1965.

Fogelson, Robert M. The Fragmented Metropolis: Los Angeles 1850-1930. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

“John Ferraro Building Los Angeles Department of Water and Power Headquarters.” AC Martin. Accessed September 12, 2018. www.acmartin.com.

“Los Angeles Department of Water and Power General Office Building (John Ferraro Building),” Los Angeles County, California. City of Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument, 2012. (CHC-2012-1944-HCM).

Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. Water, Power and the Growth of Los Angeles. Los Angeles: Department of Water and Power, 2002.

“The Water and Power Building.” Dedication program. Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, June 24, 1965.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.