You are here

Hearst Castle

In his private 1929 correspondence, aristocrat and future British Prime Minister Winston Churchill depicted newspaperman William Randolph Hearst as nouveau riche. This man was “most interesting to meet, and I got [to] like him—a grave simple child...playing with the most costly toys. A vast income always overspent: Ceaseless building and collecting not very discriminatingly works of art.” As Churchill suspected, Hearst’s La Cuesta Encantada (“Enchanted Hill”) was a country house typical of elite Americans wanting to put their taste and social status on display.

Hearst was a noted giant in publishing, but he had inherited considerable cash and land from his mining magnate father, George. Flush from fruitful investments in Nevada silver, Montana copper, and South Dakota gold, George purchased 48,000 acres along California’s Central Coast. Westward expansion of the United States was the basis for Hearst’s success. By disregarding treaties with Indigenous groups, he gained access to minerals and hired workers through an open-shop labor market. Eventually, Hearst purchased the Piedra Blanca Rancho in San Simeon from Californios who were struggling to maintain their property claims after 1848. Building something akin to an Old World castle on this land shielded all these legacies from the eyes of visitors like Churchill when they visited the American West.

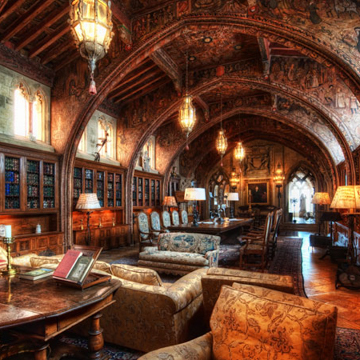

Hearst Castle is located at the top of a hill overlooking the Pacific Ocean and is accessed by a road leading up from State Highway 1, which hugs the coastline. In 1919, Hearst began construction on a small summer bungalow, which evolved into a country house consisting of four separate major buildings with 165 rooms, swimming pools, and a series of gardens. The central “castle” or “Casa Grande” building and most of the other structures are oriented to the west, facing the ocean and sunset, and are organized around a central court or plaza with a fountain and garden. Terraces on the south and north of the Y-shaped building flank this central court. Casa Grande is entered through a vestibule into a large reception room. One then moves through an elongated refectory (the “neck” of the Y) into a series of rooms meant for entertaining, including billiard and theater rooms. Upper floors were reserved for bedroom suites, libraries, and guest and servants’ quarters.

Orbiting around the Casa Grande, where Hearst entertained, were sleeping quarters, each named for corresponding views of mountains, sea, and the setting sun. All these structures shared a common Mediterranean style, a heavy blend of Moorish and medieval Christian motifs. The two identical towers poised above the whole compound were copied from the spire on Spain’s Gothic Ronda Cathedral. But Hearst also acknowledged his tastes were just as much shaped by the Mission Revival–themed architecture of the Panama–California Exposition held in San Diego in 1915. Hearst’s property also included barracks and cabins down the south side of the hill built for construction workers, gardeners, and male servants. The women on staff slept in twelve bedrooms upstairs from the kitchen. Initially, family and staff came only during summers, but by around 1924, Hearst decided to stay at San Simeon year round. Hearst and his workers ate out of the camp kitchen, even during winter storms with 80-mile-per-hour winds, for roughly three years until the Main Building’s completion in 1927.

Just to the northwest of the central court is the large, key-shaped pool, called the Neptune Pool in reference to the statue of Neptune perched on the edge. The pool is fronted by a temple structure, flanked by two peristyles, and is fed by a small waterfall feature lined with statuary. It was enlarged several times during its construction between 1924 and 1936; it now measures 104 feet long and ranges from 58 to 95 feet wide at either end.

Another indoor pool is located to the north of the main building next to a tennis court. Called the Roman Pool, it is surrounded by statues of Roman gods and heroes from antiquity. The pool’s dark mosaic tile, in blue, orange, and gold, together with the surrounding statues, is patterned after Roman baths, particularly those at Caracalla. Heavy timber beams cross the roof and, like the walls, are painted in geometric and floral patterns. This patterning, combined with the pool’s glittering mosaic tiles and light streaming in from windows on the far end of the room, creates a magical effect.

Hearst employed architect Julia Morgan to design the residence. His mother, Phoebe Appleby Hearst, had established a scholarship for young women at the University of California, Berkeley, of which Morgan was a recipient. Morgan, the first woman to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, favored public structures, and her commissions included several buildings at Mills College in Northern California, as well as the Los Angeles corporate offices of Hearst’s newspaper, the Herald Examiner. Morgan’s other work with Hearst indicated that La Cuesta Encantada served as part of his corporate infrastructure. For the guests, this estate functioned similarly to a retreat center, much like the nearby Asilomar Conference Grounds. Those YWCA buildings, which historian Kate McNeill has called a “monument to the California women’s movement” for having linked “YWCA women to powerful business interests,” were also designed by Morgan. At Hearst Castle, groups of business associates, often from Hollywood, gathered for playful recreation and bonding.

Hearst Castle melds the romantic attitude and eclectic tastes of its namesake. In Aldous Huxley’s 1939 novel After Many A Summer, the author captured this eccentric sensibility in the character Mr. Stoyte, a satirical take on Hearst. Stoyte’s country house “was Gothic, Medieval, baronial—doubly baronial, Gothic with a Gothicity raised, so to speak, to a higher power, more medieval than any building built in the thirteenth century.” For his residence, Hearst ordered furniture, ceilings, and altars from abandoned monasteries and cathedrals in war-ravaged and economically shattered Europe. La Cuesta Encantada became the singular production within which these pieces were haphazardly assembled. Hearst’s tastes echoed the imperial ambitions of his country. After all, Hearst publications helped popularize the imperialist literary genre historians recall as “yellow journalism.” Championing United States expansion into colonies once belonging to Spain’s collapsing empire, Hearst fixated on acquiring Iberian antiquities to add to his art collections and incorporate into his Castle.

Today, Hearst Castle remains a symbol of California’s capitalist and imperialist past. Flirting with bankruptcy and fascism during the 1930s and 1940s, Hearst saw his publishing empire teeter on the brink of collapse until his death in 1951. Though the estate had to sell off many assets and donated the entire property to the State of California, the collection remains sophisticated in unexpected ways. Paralleling efforts by Leland Stanford and Henry Huntington to collect Old World materials in the American West, Hearst hoped La Cuesta Encantada would eventually be home to a major cultural and intellectual institution, which he imagined as a West Coast Cloisters Museum. Instead, Hearst Castle is now a monument to a millionaire. Not one to heed advice from art dealers and academics, Hearst freely gathered a bizarre array of “high” and “low” art objects. Defying cultivated norms so comfortably and liberally mirrors recent postmodernist qualms about cultural hierarchy. Social critics from Huxley to filmmaker Orson Welles had plenty of reasons to attack Hearst for his political leanings, but culturally, his interests were much more in accord with his more democratic, predominantly white, working-class newspaper readers.

References

Churchill, Winston. Letter to Clementine Churchill, September 29, 1929. Churchill and the Great Republic, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Kastner, Victoria. Hearst Castle: The Biography of a Country House. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000.

Kastner, Victoria. “William Randolph Hearst: Maverick Collector.” Journal of the History of Collections 27. No. 3 (2015): 413-424.

MacShane, Frank. “The Romantic World of William Randolph Hearst.” The Centennial Review 8, no. 3 (Summer 1964): 293-305.

McNeill, Karen. “Julia Morgan: Gender, Architecture, and Professional Style.” Pacific History Review 76, no. 2 (2007): 229-267.

McNeill, Karen. “‘Women Who Build’: Julia Morgan & Women’s Institutions.” California History 89, no. 3 (2012): 41-74.

Nasaw, David. The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.