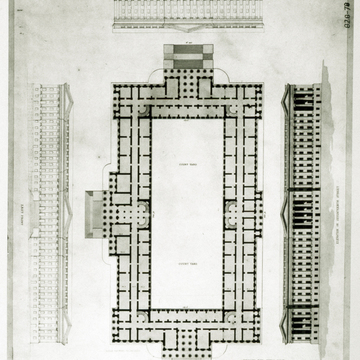

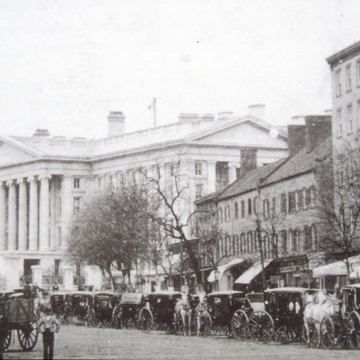

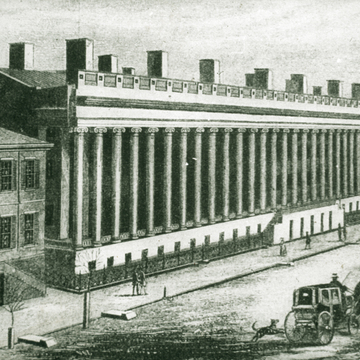

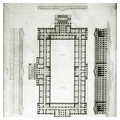

The Treasury Building was constructed wing by wing over a thirty-five-year period beginning in 1836. On 4 July 1836, President Andrew Jackson selected Mills's design over that of his only known competitor, William P. Elliot, Jr. This design called for an E-shaped building with the spine along 15th Street and three porticoed wings facing the White House. Under Mills's superintendence, the spine and central wing were constructed between 1836 and 1842; it was one of three impressive office buildings he designed for Washington using fireproof brick-vaulted construction throughout. The major architectural feature remaining in Mills's section of the Treasury Building is the 466-foot unpedimented Ionic colonnade along 15th Street. The Ionic order he selected, with an anthemion necking band below the volutes, derived from the Erechtheum on the Acropolis. It was the most widely copied of the Greek Ionic orders in America. The present facade differs in two respects from Mills's original plan. The only pedimented pavilions in Mills's initial scheme were in the centers of the north and south wings; today there are pedimented pavilions at both ends of Mills's colonnade, a result of Thomas U. Walter's 1855 design for completing the building. Mills also constructed a double-ramped staircase on the sidewalk in the center of the facade that led to the main entrance behind the colonnade. It was removed during renovation in 1908. Mills's colonnade, originally constructed of brown Aquia sandstone, was replaced by granite in 1908, but behind the colonnade, the original coffered ceiling of sandstone survives. Four of the original Aquia columns were saved and form a picturesque ruin in Pioneer Park in Lincoln, Nebraska.

Mills's sources for this monumental colonnade drew upon antique and modern examples, such as the Temple of Diana at Ephesus, which inspired its size and staircase arrangement, and Alexandre Brongniart's instant classic, the Paris Bourse (1808). Two factors have altered Mills's facade: substitution of the bold and crudely carved sandstone columns by more refined granite ones in 1908 has robbed it of its elemental power. Raising the original basement was due to repeated

The interiors of Mills's wings in the Treasury Building are the least spatially satisfying of any of his three Washington office buildings. The corridors are narrow and dark, the result of severe budget constraints and the need to create the maximum amount of usable office space. Unusual at the time was the regular spatial arrangement of groin-vaulted office cubes on both sides of the central barrel-vaulted corridors, the first large modular office building in the United States. At the Treasury Building (and the Patent Office Building [see DE15.2, p. 189] being constructed simultaneously), Mills capitalized on this system of fireproof vaulting in larger buildings than those where he had previously used it in South Carolina and New England. The most beautiful feature of his interiors is his fireproof double flying staircase carried through four stories, constructed by cantilevering each tread from the wall and corbeling the treads against one another. The complementary curves of the scalloped treads and converging semicircles of each set of stairs, combined with the airy lightness Mills achieved with the solid marble treads, make this staircase in company with his others at the Patent Office ( DE15.2, p. 189) and General Post Office ( DE15.3, p. 191) the most magnificent monumental stone staircases in America surviving from this period. A few of the original fireplace mantels remain; they are unique designs by Mills and the German-born and -trained sculptor Ferdinand Pettrich. Cast in a composition material and called “Etruscan,” they are small in scale and crudely classical in their ornamentation.

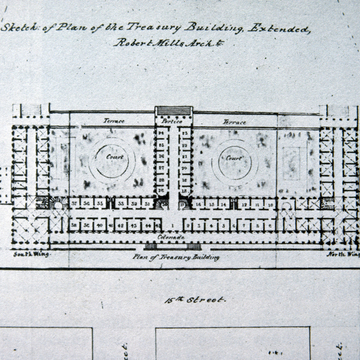

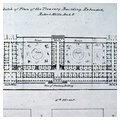

In 1855, Thomas U. Walter proposed a design to complete the Treasury Building in the form of the figure eight. It called for imposing porticoes projecting in the centers of the south, west, and north facades and pedimented porticoes at each end of the east and west facades. The central portico facing the White House was the most fully developed, with its octastyle porch projecting in front of a colonnade in the same manner as Latrobe's much-admired east facade of the Capitol. The octastyle north and south porticoes masked deep colonnaded entries in a manner similar to the entrance to the Athenian Acropolis. This envelope was the basis for completing the exterior of the building, but the interiors followed designs of the individual architects in charge of construction between 1855 and 1869. Recognition of the need for permanent materials in public buildings resulted in the use of Dix Island, Maine, granite on all three extensions. While Mills's interiors were barrel or groin vaulted in brick, in the extensions there are cast-iron columns and beams in conjunction with minor brick vaults, so interior spatial effects there are entirely different. With the exception of columns at the main staircase (derived from the Temple of Apollo at Delos), Mills's interior walls are unarticulated plaster; those in the extensions are punctuated by cast-iron Corinthian pilasters carrying an ornate cast-iron frieze.

Ammi B. Young was named Supervising Architect of the Treasury Department in 1852 and in 1855 was put in charge of constructing the south and west wings of the Treasury Building, although Isaiah Rogers took over the west facade in 1862, when Young retired. Young's plans followed Walter's three-story scheme but introduced the high staircase projecting from the south wing, due to the declivity of the land. Young spread his stairs below and in front of both cheek blocks, as on the east front of the Capitol.

Young introduced a pronounced grid effect by interposing horizontal bands between the second and third stories. These were not mere belt courses but plain bands that stepped forward and then back in triple tiers, introducing an additional three-dimensional element onto an already sculpted wall surface. The sharply defined edges of each unit in Young's facade were imposed by the hardness of the granite. He exploited the nature of the granite to achieve a contrast between the broad and relatively slick surfaces of the stone and the layered effect of the facade composition. One striking example is his window framing (especially notable in the lintels), where both the plain architrave and cyma reversa moldings of the jamb are cut from single blocks of granite. These refinements, probably an outgrowth of an austere style of granite building initiated by architects in Boston during the 1830s, were continued by the architects who followed Young on the east and north facades.

On the interiors of his south wing, Young replaced the acanthus leaves of the Corinthian order with eagles beneath the volutes and introduced keys grasped by a fist, the

Monolithic granite columns on the west wing exterior (1855–1864) were cut from the quarry on the diagonal, a remnant of Young's and Isaiah Rogers's New England training in the Boston granite style of construction. Between 1861 and 1863, Rogers was the engineer in charge of the Bureau of Construction of the Treasury Department and then served two years as the supervising architect. On the exterior, Rogers replaced the stone balustrade of the east and south facades with giant cast-iron anthemions, removed when the north wing was begun. The most interesting interior features of the south wing were the decorative cast-iron walls for four burglar-proof vaults designed and patented by Rogers in 1864 and constructed in the Treasury Building by George R. Jackson of Burnet and Company of New York. One example survives in the northwest corner on the main story. Two layers of cast-iron balls sandwiched between wrought-iron and steel plates rotate when struck by drills or other burglar's tools, preventing penetration of the wall. The outer layer of Rogers's vault is ornamented with gilded cast-iron heraldic eagles grasping the Treasury key and set within circular frames. They alternate with roundels containing the Treasury Department seal; both motifs are set off by large and richly decorated cast-iron anthemions.

Construction of the north wing was begun after the Civil War. Its forecourt had to be sunk to accommodate the full height of the building against the incline of the hill. This siting, in conjunction with its unlit facade, tends to diminish the impact of the north portico. To achieve a semblance of exterior symmetry, its architect, Alfred B. Mullett, had proposed narrowing 15th Street in order to build a monumental portico in the center of Mills's colonnade, but it was never carried out. Although Mullett followed the exterior pattern established by his predecessors, he designed his interiors in the Renaissance Revival style while his predecessors carried over the Greek Revival of the exterior to their interiors. Mullett's most remarkable space was the Cash Room, a double-storied rectangular room (72 feet by 32 feet, and 27½ feet tall) divided by a balcony with windows on the long south wall. It originally functioned as a bank for the government. With the exception of the iron-beamed flat ceiling, gilded plaster cornice, bronze balcony railing, and bronze doors (originally wood), seven varieties of variegated Italian and American marbles are used throughout. The subdued richness of these colorful materials is matched by well-proportioned architectural and emblematic decoration. Superimposed sets of double pilasters circumscribe the entire room, Corinthian below and composite above. The composite order carries a bracketed cornice composed of plaster shells. The bronze balcony railing by J. Goldsborough Bruff contains symbols of the supervisory responsibilities of various Treasury Department bureaus. Grapes, corn, and cotton relate to the agricultural basis of the American economy and shells and starfish to the commercial products; the caduceus refers to the Marine Hospital Service administered by the department. Three original bronze gas chandeliers were removed from the Cash Room in 1890; electrified replicas were installed in 1987. The Treasury Building contains some of the finest and least-known early and mid-Victorian interiors in America.

The landscape plan of the Treasury