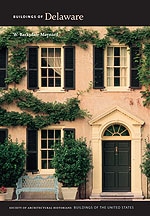

William Corbit, tanner, apprenticed in Philadelphia before returning to his native Delaware in 1767. His tannery on the Appoquinimink River thrived, as did his farm holdings, and soon he built a five-bay, twenty-two-room mansion, Delaware's finest pre-Revolutionary house. It faced a now-vanished road that led to the tannery and boat landing. The 89,250 bricks may have been burned locally, but stone for the cellar, stringcourse, and lintels was brought in, with “Stone from Chester [Pennsylvania]” listed in Corbit's account of construction costs (Sweeney, 1989). A Philadelphia lumber firm provided pine and cedar boards; hinges, screws, and locks came from Wilmington or Philadelphia. Nails and window glass were shipped, too. The cornice, with big mutules instead of modillions, is exceptionally grand. The Doric front door, or “frontispiece,” is like the one at the now-demolished Stamper House, Philadelphia (1764). From a lead-covered roof deck or “terrass” with “Chineas Lattis” railing, Corbit surveyed his business and farm operations. Painting the house inside and out with “Oyl & Whitelead & paints” cost Corbit a large sum.

Exterior and interior woodwork was fashioned by the otherwise-unknown Robert May and Company, an educated and skilled craftsman, and his crew of carpenters. May left an invaluable itemized list of his activities in the bill for Corbit, part of the reason the place is, in Winterthur Museum curator John Sweeney's words, “one of the best-documented houses in America.” The center passage, double-pile plan is the embodiment of full Georgian architecture. The largest space in the house is upstairs, the “long room” or drawing room, which bears an uncanny resemblance to that of the Powel House, Philadelphia (1765), with some of the fretwork moldings (described by May as “Base & s[u]r base a frett in each”) literally identical. In both houses, Abraham Swan's Designs in Architecture (London, 1757) provided inspiration. May's bill refers to the drawing room's ornamental details: “Pilasters,” “Tabernacle frame,” “Mantle cornice.” Splendid carpentry throughout the house consumed almost half the construction budget.

Corbit, twenty-seven years of age when construction began, may have expected a thriving city to develop around his homestead, but this never happened, and “Castle William” (as locals called it in the nineteenth century) loomed over the modest community for generations. H. Rodney Sharp fell in love with the old house when he lived across the street in the Brick Hotel in 1900. Years later, in 1938, he heard that the building, then empty except for a charwoman inhabiting the upper floor, was slated to be converted to apartments. He bought the place and, with architect Lindsey, reversed nineteenth-century changes and returned original elements to their proper locations in the house, which was exceptionally intact, even to the Chinese railing atop the roof. Sharp donated the mansion to Winterthur Museum (CH10) in 1958, which long operated it as part of the Historic Houses of Odessa, toured by 9,000 visitors annually. Furnishings in the National Historic Landmark follow William Corbit's 1818 inventory.