One of the oldest public buildings in the United States and now a state museum, this National Historic Landmark is Delaware's most significant English-colonial edifice. It served as meeting place of the Delaware General Assembly (1704–1776) and as state capitol (1776–1777) in addition to housing all state and federal courts for generations. Restoration architect Kruse made sketches that showed four stages in its development, starting with an earlier courthouse (c. 1689), established by William Penn and burned in a failed jailbreak in 1729. Its stone foundations, excavated by C. A. Weslager, are visible though an opening in the floor. The central block of the present building replaced it, originally with a hipped gambrel roof and plaster cove cornice. A dog-legged stringcourse steps up, not once, but twice, upon turning the corner, as on the Town Hall, Philadelphia (1707–1710, demolished 1837). Two small wings were added, the east one (sometimes wrongly said to be seventeenth century) having been altered by the time Benjamin Henry Latrobe sketched the building from across the street in 1805. At various times the roof was rebuilt, the cupola replaced, and the building stuccoed and given a heavy, Gothic Revival porch around the door. The west wing of the 1840s was fireproof, with stone sleepers from the New Castle and Frenchtown Railroad (see New Castle and Frenchtown Railroad on p. 162) used in its foundations. In time, there was talk of replacing the aging structure, but nothing was done, and in 1881, the county government moved to Wilmington.

For years subsequently, the building was managed by the Trustees, who leased it to various parties. During the period that New Castle lay on a main U.S. north-south automobile route, Horace L. Deakyne operated a popular Colonial Revival tea room (1926–1942). The first restoration removed the porch and salmon-colored stucco and introduced the balcony; a second, more sweeping, stabilized the structure, lowered the windows to their original level, and returned the building to a colonial appearance inside and out. (Deep cracks were discovered, which might eventually have caused the building to collapse.) Fortunately, local objections forestalled the planned demolition of the west wing and rebuilding of the roof. In 1957, Kruse acquired 18,000 old bricks for restoration purposes by demolishing the abandoned Maple Lane Farm north of town.

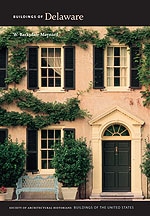

The mellow, weathered walls of the Court House show how bricklaying changed over time, from English and glazed-header Flemish bonds of the 1730s to common bond of the 1840s. The terrace in front of the building, approached by deeply worn steps and surrounded by an iron railing (1830), postdates the leveling of the streets as stipulated by the Latrobe-Mills survey. This has long been a popular place to congregate, and deep grooves at the east corner are attributed to shad fishermen loitering and sharpening their knives. Prominent in the spacious courtroom is a pair of tall Doric pillars supporting the ceiling. All else in the room is restoration. This space has witnessed many historic events, including Catherine Bevan being sentenced in 1731 to be burned alive for the murder of her husband; also, the trial in 1848 of abolitionist Thomas Garrett, presided over by the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, Roger B. Taney. The second floor originally housed the colonial assembly and, later, jury rooms. Thousands of tourists and schoolchildren visit these historic chambers annually. The exterior has been refurbished (2003, Frens and Frens and Bernardon Haber Holloway) and the white trim repainted in colors found by paint analysis: creamy yellow on the older parts, gray on the wing of the 1840s.