Between 1825 and 1838 New Echota was the capital of the Cherokee Nation, whose land during that time extended throughout the region of northwest Georgia (covering ten Georgia counties today), as well as parts of Tennessee, Alabama, and North Carolina. After the American Revolution, white settlers increasingly intruded onto Indian lands west of the fall line and ultimately succeeded in pressuring the new federal government to fulfill its promise to remove the Indians entirely from these western lands. Much of the territory was home to the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole nations. The issues of land distribution and Indian removal informed a notorious chapter in Georgia history extending from the Yazoo Land Fraud of 1795 to the Trail of Tears in 1838.

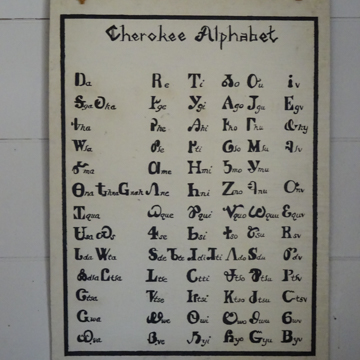

During this period, the Cherokees in north Georgia responded to rapidly changing conditions by adapting to the white settlers’ way of life. They organized their tribal groups into a Cherokee Nation and began to meet annually at a council house built in 1819 (rebuilt 1822). Around the council house the Cherokees laid out New Town, a settlement of fifty-foot wide streets, a sixty-foot main street, a two-acre town square, and 100 one-acre lots. By 1825 the Cherokees had established their national capital at New Town, which they now renamed New Echota. Having developed a Cherokee alphabet, in 1827 they built a print shop and began publishing the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper (in English and Cherokee), which appeared weekly between 1828 and 1834 and was distributed nationally and in England. The following year, the Cherokees built a Supreme Court House where, between 1823 and 1835, some 246 disputes (mostly civil) were adjudicated. With no prison, those found guilty were hanged, whipped, or fined. When court was not in session, the Supreme Court building was used as a school and, on Sundays, a church. By 1830 the town consisted of ten dwelling houses, three government buildings, four stores, and some twenty-five outbuildings including corncribs, smokehouses, and a stable. No longer hunters and fishers, the Cherokees were now permanent settlers who developed small farms throughout the region; over ninety percent of Cherokees were farmers according to the 1835 census. It is estimated that by 1837, there were 4,000 Cherokee buildings in the Georgia section of the Cherokee Nation. The capital of New Echota embodied a culture far removed from contemporary stereotypes of Native Americans as uneducated, un-Christian savages.

The year before New Echota was established as the Cherokee capital, the fierce Indian fighter “Long Knife” (Andrew Jackson), who had already driven Creeks and Seminoles out of Georgia, ran for President of the United States. John Quincy Adams was elected in 1824, but Jackson ran again in 1828 and won the presidency. Two years later, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, legislature that authorized the purchase of Indian tribal lands within the states in exchange for land further west in the territories beyond state boundaries. The discovery of gold on Cherokee land in north Georgia in late 1829 added to the pressure from white settlers to rid the territory of Indians. The Georgia legislature passed laws unfavorable to Cherokees and surveyed Cherokee land, dividing it into land lots that would be transferred to whites through lotteries.

The Cherokee Nation opposed all such action. They sought to advance their rights through judicial action. Their resistance to leaving their native lands was at first bolstered by Jackson’s own earlier statements that Indian removal should be voluntary and that those who wished to stay on Indian lands in north Georgia could do so, as long as they abided by United States law. But such assurances proved to be false promises. Cherokee resistance culminated in the 1832 United States Supreme Court decision, Worcester v. Georgia, which provided that Georgia could not impose its laws upon Cherokee tribal lands. President Jackson, still dedicated to Indian removal, is said to have remarked, “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.”

Convinced that the Supreme Court decision supported their right to stay or leave voluntarily, in 1835 twenty representatives of a small group of Cherokees signed the Treaty of New Echota, which defined terms under which the Cherokee Nation ceded all its territory in the southeast and agreed to move west to the new Indian Territory (Oklahoma). It soon became clear that those who wanted to stay would not be allowed to do so. The final clause of the treaty—the major reason the treaty was unanimously accepted by the contingency of natives who signed it—allowed individual Cherokees to remain on 160-acre allotments and become citizens of the state of Georgia. However, it was struck out by President Jackson before he signed it; the Cherokee were given two years to leave. On the eve of the deadline for removal, a petition containing 15,665 signatures, almost the entire Cherokee Nation, reached Cherokee representatives in Washington, D.C. The petition argued that the treaty negotiators did not represent the Cherokee National Council and that the land cession was illegal. Many Indians believed the Treaty of New Echota was a betrayal, and two of the leaders of the small Cherokee contingency that had signed it were assassinated. Although some Cherokees in Georgia and throughout the southeast were beginning to leave voluntarily, most Cherokees continued to claim north Georgia as their home. In 1832–1833, however, the last three of eight separate Georgia land lotteries had awarded Cherokee land to white settlers, who were rapidly moving onto Cherokee lands to claim their prizes—houses and outbuildings included.

When the two years allowed for voluntary departure of the Cherokees from Georgia expired, the Cherokees who resisted removal became subject to military action. President Jackson sent General Winfield Scott to administer the Indian removal with the aid of 7,000 federal troops and state militia. Thousands of Cherokees were forced into encampments within military forts (including Fort Wool at New Echota), and in 1838 the ordeal known as the Trail of Tears began. During the spring, about 2,200 Indians left the southeast for resettlement in the so-called Indian Territory of Oklahoma, but summer heat, disease, and a lack of food along the way encouraged a delay in executing further removals until cooler months. In the meantime, an agreement was made that Indian leaders could manage their own migration. However, conditions were dire on crowded keel boats, on wagons, and for most who walked. Tragedy still lay ahead.

After 1838 and the Trail of Tears, the Cherokee capital at New Echota completely disappeared due to new towns established by white settlers throughout the middle of the nineteenth century. Almost 115 years after the Trail of Tears, a group of Calhoun citizens stood at the open grassland of the New Echota site, where only the house of the only missionary, Samuel E. Worcester, still remained. The citizens decided to purchase the 200-acre Cherokee capital site, now farmland, and rebuild the town. In August 1953, Henry Malone located the exact site of the town and archaeological excavations conducted by Clemens de Baillou in 1954 located building sites, roads, and landscape features from the Cherokee era. In 1956 the New Echota Foundation deeded the New Echota property to the state of Georgia. Also in 1956, Vann’s Tavern, threatened by the formation of Lake Lanier near Gainesville, was moved from Oscarville, a Floyd County Cherokee site, to New Echota; it was the first building reconstructed. A well house and log barn followed. From 1957–1959, architect Henry Chandlee Forman, who also restored Chief Vann’s House in nearby Murray County, restored the 1827–1828 Worcester House, and in 1960 the 1829 Supreme Court House was reconstructed by Tom Little. By 1962, based on written descriptions of the building, Little also reconstructed the Print Shop, where the Cherokee Phoenix was published. With these several buildings reconstructed or restored, the New Echota site was dedicated and opened to the public. The museum was built in 1969, and nineteen years later the Cherokee monument, erected in 1931 in the New Echota cemetery, was moved to the museum entrance.

In 1973 New Echota became a National Historic Landmark. Interpretation of the site in the 1980s and 1990s focused on the domestic and farming life of the Cherokee capital. In 1983, a “middle-class” Cherokee dwelling, dating from around 1830, was relocated from a nearby Gordon County Georgia site to New Echota, and three outbuildings from Tennessee (a barn, corncrib, and stable) were moved to form a farmstead grouping. A similar grouping of a small cabin, with corncrib and stable, was formed in 1991 on land lot 25 in New Echota as a “common” Cherokee farmstead. In 1994, the Council House of 1822 was reconstructed. In all, the buildings at New Echota tell the story of a nation of Native Americans who were displaced during a volatile period of America’s westward movement beginning on the frontier in Georgia.

References

Sparks, Andrew. “Indian Village Comes to Life Again: New Echota gives visitors a surprising picture of the Cherokees.” Atlanta Journal Constitution Magazine (news clipping), n.d.