You are here

Minidoka Internment National Monument and Historic Site

Minidoka Internment National Monument and Historic Site is a memorial for over 13,000 people of Japanese ancestry from Washington, Oregon, and Alaska interned at the southeastern Idaho site during World War II. From 1942–1945, over 140,000 Japanese Americans and resident aliens from Japan, living primarily on the West Coast, were interned in ten government camps located in inland areas. The internment camps imprisoned people of Japanese ancestry, whom the government believed might sabotage military installations and industrial sites because of their loyalty to Japan. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, allowing for the evacuation and internment of people of Japanese, German, and Italian ancestry living on the West Coast. Significantly, the majority of the people who were forced to leave their homes, businesses, and lives behind and enter the internment camps were of Japanese ancestry.

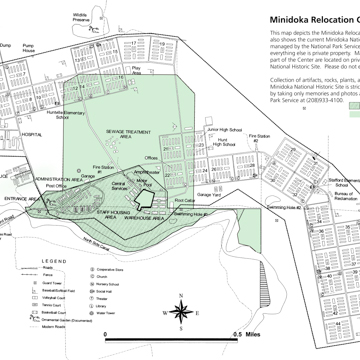

Referred to as Camp Minidoka, this National Historic Site preserves over 72 acres of the original 34,000-acre Minidoka War Relocation Center. The center was developed by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), a new government agency responsible for managing the relocation process, determining camp locations, and implementing camp design and construction. Camps were located in rural, wide-open areas owned by the federal government that were far removed from national defense sites. Locations were determined by adequate water supply, access to transportation including railroads and major highways, and a climate that could support large-scale agricultural production.

Minidoka, located in south-central Idaho, met all the WRA requirements. The camp was located on a high desert plain near the rural town of Eden in an area known as Hunt, approximately 16 miles from Jerome. The area was unincorporated and covered in scrub brush. The camp was named Minidoka after a neighboring county and a federal irrigation dam project. Historians note it was a Native American name arbitrarily given to one of the first Union Pacific train stops in the area. A significant pre-existing feature at the south edge of the site is the North Side Canal, which provided irrigation water and determined the crescent shape of the site plan. While most other camps were laid out on a grid, in Minidoka, the combination of the winding canal and uneven ground prompted a layout offset from the grid, providing variation and a stronger separation of the administration and residential areas.

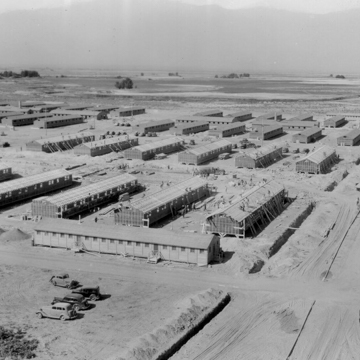

Construction began on June 5, 1942, with a design based on a modified United States military theater of operations model, which was typical for the camps. This model was selected because it called for temporary structures built from available materials. The majority of Minidoka’s structures were wood framed and covered with tar paper. A limited number of basalt rock structures were built at the entrance of Minidoka including the visitor’s reception building and military police station. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers served as the designer and contractor of the camp, and Morrison Knudsen was awarded the $4.6 million contract as the local construction company.

Minidoka officially opened on August 10, 1942, after three months of construction. The camp was a secure military installation with barbed-wire fences and eight guard towers. It was designed to support 36 residential blocks with barracks-style housing. Each block had 12 barracks, 20 by 120 feet in size, that were originally designed for military troops but here each barrack was subdivided into six units for family housing. A centrally located latrine, shower, and laundry building, and mess and recreation halls completed the block design. Residential areas also had the typical stores and services of any town including general and dry goods stores, barber and beauty shops, catalog order stores, dry cleaners, and radio and watch repair shops, among others. The camp was made up of over 600 structures including four schools, a gymnasium, two fire stations, a military police station, and a hospital, along with administration buildings, warehouses, agriculture buildings, a water tower, and sewage treatment plant.

During their incarceration, Minidoka internees cleared land for large-scale farming activities and produced crops and livestock for camp use and resale, constructed and repaired canals, and provided vital agricultural labor for the region. With many area men serving in the military, the labor provided by the internees was invaluable. Minidoka internees also served in the military, and Minidoka is noted for the large percentage of men who enlisted compared to other camps. Living in the camp was frustrating from the beginning as construction was incomplete and resources limited. Each family lived in a small, 400-square-foot room furnished with military-issue cots, a blanket, and a coal stove. With these limited furnishings internees had to be resourceful in creating a place that functioned as home. They designed and built gardens, lined paths with stone, and built furniture out of scrap lumber. They ordered rugs, bedspreads, and blankets from catalog stores, and had friends on the outside send calendars and posters to pin on the sheetrock walls. Internees continued with daily pursuits in an effort to create a degree of normalcy in an untenable situation. Internees were active in outdoor pursuits, especially baseball, and they built nine playing fields with picnic areas. They also created swimming spots on the canal, and eventually two swimming pools.

At its peak Minidoka housed 9,397 people. By the time it closed on October 26, 1945, the population had decreased to below 6,000. On February 10, 1946, Minidoka was turned over to the U. S. Bureau of Reclamation for the dispersal of land, structures, and resources. Returning soldiers and area farmers purchased the land and relocated structures but the dispersal project continued into the 1960s. Today the majority of the original Camp Minidoka is privately owned, with reused structures serving as houses and outbuildings throughout southern Idaho.

Minidoka Internment National Monument was created on January 17, 2001, and became a National Historic Site in 2008. Ruins including the wartime entrance, reception building chimney and rock walls, concrete foundations and footings, a root cellar, and rock lined paths and gardens, along with other cultural landscape elements remain. Today, the site is a reminder of a grievous injustice and a testament to the grace of the survivors and their families. It is also a reminder to all Americans of shared responsibility in a democratic society.

References

Arrington, Leonard, J. The Pride of Prejudice. Delta, UT: Topaz Museum, 1997.

Burton, Jeffrey F., Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord. “Confinement and ethnicity: An overview of World War II Japanese American relocation sites.” Anthropology 74 (1999, rev. July 2000).

Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942. Headquarters Western Defense Command and Fourth Army, Office of the Commanding General, Presidio of San Francisco, California. Washington, DC: GPO, 1943.

Wakatsuki, Hanako. “Minidoka.” Densho Encyclopedia. Accessed January 8, 2015. http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Minidoka/.

“Japanese American Internment during World War II.” Friends of Minidoka .Accessed May 12, 2015. http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Minidoka/.

“Chronology of Japanese Incarceration.” Japanese American National Museum. Accessed May 21, 2015. http://www.janm.org/.

Meger, L. Amy. “Historic Resource Study Minidoka Internment National Monument.” National Park Service, U.S. Department of Interior, 2005. Accessed June 29, 2016. http://www.nps.gov/.

Mercier, L. “Japanese Americans in the Columbia River Basin.” Columbia River Basin Ethnic History Archive, Washington State University, Vancouver. http://archive.vancouver.wsu.edu/.

“Minidoka.” National Park Service, U.S. Department of Interior .Accessed June 29, 2016. http://www.nps.gov/.

“Minidoka National Historic Site.” Friends of Minidoka. Accessed May 12, 2015. http://www.minidoka.org/.

“Minidoka: National Historic Site.” National Park Service, U.S. Department of Interior. Accessed May 12, 2015. http://www.nps.gov/miin/index.htm.

“National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Minidoka Internment National Monument.” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2007. http://www.nps.gov/.

“NJAHS Confinement Sites,” USF Gleeson Library Digital Collections. Accessed May 26, 2015. http://digitalcollections.usfca.edu/.

Tamura, T. Minidoka: An American Concentration Camp. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Press, 2013.

“Transcript of Executive Order 9066: Resulting in the Relocation of Japanese (1942).” 100 Milestone Documents. Accessed May 21, 2015. http://www.ourdocuments.gov/.

Zontek, Terry, "Minidoka Relocation Center," Jerome County, Idaho. National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form, 1979. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.