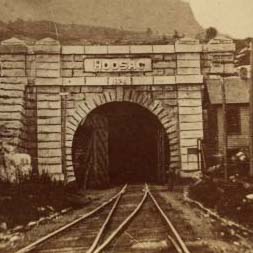

The Hoosac Tunnel passes through 4.75 miles of solid rock in the northwestern corner of Massachusetts. Laboriously constructed between 1851 and 1875, this still active single-track train tunnel held the position as the longest in the United States and second longest in the world at the time of its completion. The Hoosac Tunnel represents an extraordinary feat of American engineering skill that embodies the era’s technological, industrial, and commercial developments. The tunnel’s construction reveals the historic importance of transportation networks, especially rail, to the regional and statewide economy. In a time known for its laissez-faire capitalism, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts played an active role in financing, building, and even operating the Hoosac Tunnel. Its immense scale (it displaced approximately two million tons of rock) and tragic human cost (nearly 200 workers died during its construction) illustrate the powerful and seemingly overwhelming forces of industrial and commercial growth in the mid-nineteenth century.

The 1825 completion of the Erie Canal diverted trade from Massachusetts and positioned New York City as the nexus of regional, and soon global, commerce. Eager to tap into this lucrative network that connected Midwestern farms with markets in the East and beyond, businessmen and state officials in Massachusetts contemplated a cross-state canal system, but settled on a rail line as that technology was growing more reliable. The subsequent Western Railroad (eventually part of the Boston and Albany Railroad), built in 1841, followed a route through the southern part of the Massachusetts to New York, where it turned north to Albany.

The Western Railroad’s circuitous route crossed over the Berkshire Hills and included steep grades and tight turns that were difficult for trains to navigate. Only a few years after the Western’s completion, businessmen began formulating a new, northerly route that would connect the town of Greenfield, Massachusetts with Troy, New York—then a center of industry and trade. This shorter and straighter route, though, involved tunneling through the wide Hoosac Mountain.

Undeterred, the interested parties formed and received a charter for the Greenfield and Troy Railroad in 1848 and began construction on the Hoosac Tunnel in 1851. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts voted, following much debate, to loan the Greenfield and Troy two million dollars contingent upon the tunnel’s progress. Indeed, boring a tunnel of such unprecedented length required not only vast expenditures, but also new methods and technology, some of which emerged while the tunnel was under construction.

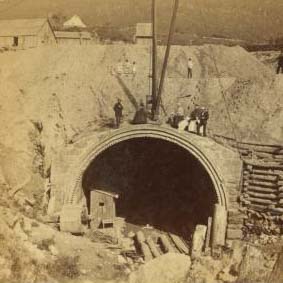

Under the direction of noted civil engineer Herman Haupt (the first of several chief engineers), digging began simultaneously on the west and east sides of the mountain, with the intention that the two tunnels would meet in the middle. Achieving this required complex surveying techniques. First, surveyors cleared a path across the top of the mountain, determined a straight line, and fixed east and west portals at each entrance. Subsequently, engineers built four sighting towers across the top of the mountain that could visually relay a true straight line to workers in either shaft. In addition to ensuring its appropriate alignment, engineers built the tunnel at a slight grade for drainage. Incredibly, the tunnel design achieved a very small margin of error, just over a half inch.

At first, workers employed hand drills to chisel and black powder to explode their way through the hard rock. Though employing some of the best engineers in the country, none had experience with a tunnel this long. As a result, progress was slow and dangerous. Over the course of construction, 193 workers died from a variety of work-related accidents. The tunnel’s construction delays, combined with Greenfield and Troy’s default on state loans, forced the Commonwealth to assume control of the project in 1862. The state hired new contractors and appointed Canadian Walter Shanly as chief engineer. Shanly sped up work by digging down through the middle of the mountain, thus creating two additional faces from which to excavate. Additionally, state-sponsored engineers introduced new pneumatic drills and, importantly, the newly invented explosive, nitroglycerine. The Hoosac Tunnel construction was the first commercial application of the liquid explosive and an early adoption of electric blasting caps. These novel strategies and technological improvements greatly increased the pace of work, and the tunnel opened to train traffic in 1875.

Because the Commonwealth had invested so heavily in the politically contentious project, it operated the Hoosac as a toll tunnel for the first decade. This, however, proved to be unfeasible and anathema to the capitalist system that ruled railroads, and the Commonwealth sold the tunnel to the Fitchburg Railroad in 1885. As had been the tunnel founders’ hope, the Hoosac became a vital economic link and carried sixty percent of Boston’s export trade by 1895. The conduit connected industries in western Massachusetts and across the state with new markets in the Midwest and beyond.

The Hoosac Tunnel survived the upheavals and decline in the railroad industry and continues to carry freight. Pan Am Railways operates it, and, while visitors can see the east and west portals, the tunnel itself remains off-limits. However, the nearby Western Gateway Heritage State Park in North Adams, located in a historic train depot, offers interpretation of the Hoosac Tunnel’s creation.

References

Byron, Carl. A Pinprick of Light: The Troy and Greenfield Railroad and its Hoosac Tunnel. Brattleboro, VT: S. Greene Press, 1978.

Franceschi, J. Michael, “Hoosac Tunnel,” Berkshire County, MA. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1973. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Karwatka, Dennis. “The Hoosac Tunnel.” Tech Directions67, no. 9 (April 2008): 9.