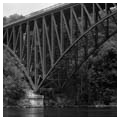

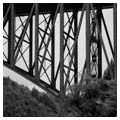

The French King Bridge soars 135 feet above the Connecticut River, spanning a narrow gorge between the towns of Erving and Gill. The bridge’s dramatic display of steel construction and American engineering skill exemplifies the development of a modern, automobile-centered transportation network in Massachusetts. Completed in 1932, this bridge serves as the eastern terminus of the Mohawk Trail, a scenic highway that follows a former Native American trail, an important route for English settlers, and an early turnpike. Now designated U.S. Route 2, this former footpath has become both an important commuting corridor as well as a popular scenic byway. The French King Bridge constitutes one of U.S. Route 2’s crowning landmarks.

The Mohawk Trail spans the northwestern third of the state, from Greenfield in the east to North Adams in the west. It is a route laden with historical associations and legends. Though the original Native footpaths have long been lost, the Pocumtuck tribe in the Connecticut Valley had extensive trail networks along the contemporary route that connected it with tribes of the Five Nations in eastern New York, including the Mohawks. In the late seventeenth and throughout the eighteenth century, English settlers utilized and adapted these paths as part of their westward expansion. The Native trails responded to the environment by following streams, rivers, and forest edges.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, private interests began developing a road system along this route that would better facilitate the movement of people and agricultural goods. Individuals built several sections of private turnpikes, which were higher-quality roads that required users to pay a toll. These private roads eventually defaulted and became free county-operated roads.

By the twentieth century, the Mohawk Trail was a well-established, though somewhat perilous, transportation corridor. The roads along it received little maintenance and followed a precipitous, winding course through many sections. Though the Mohawk Trail adequately served nineteenth-century (non-railroad) transportation technology, it failed to meet the standards of the new automobiles that were gaining popularity in the early twentieth century. In order to accommodate these motorized vehicles, the state instituted a massive road improvement campaign that included rebuilding the Mohawk Trail from Greenfield to North Adams. Completed between 1912 and 1914, the project rendered the centuries-old route compatible with the newest technology. The state officially designated the new highway as “The Mohawk Trail,” in reference to the western tribes to which the route historically led.

Just twenty years after the completion of the highway, though, authorities once again deemed the road insufficient for automobile traffic. Firmly ensconced as the dominant mode of personal transportation, cars had greatly increased in number and speed. This, in turn, inspired a reconfiguration of certain parts of the Mohawk Trail. In particular, the state pointed to the section between the villages of Millers Falls and Turners Falls as especially dangerous due to steep grades, right-angle turns, narrow bridges, sharp curves, and an at-grade railroad crossing. A surveying team determined that the solution was to reroute that entire segment of the highway north of the two small towns. The new route straightened the road and required a large bridge to carry cars across the Connecticut River.

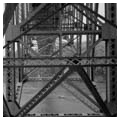

The Massachusetts Department of Public Works (MDPW) desired a bridge that matched the spectacular scenery of the gorge and displayed the height of the period’s technological ability. George E. Harkness, an engineer for the MDPW, designed the steel deck, three-span arch bridge. Due to the river’s swift currents, varying depths, and a legal impediment to reducing water flow to downstream hydroelectric stations, Harkness had to avoid placing temporary or permanent piers in the water. Fortunately, suitable rock for the foundations was located just below the surface on both banks of the river. The prohibition of building in the water also rendered it necessary to employ the cantilever arch system of bridge construction. In this method, the crew built a portion of the bridge on one side of the river and then moved across to complete the other side, eventually bringing them together in the middle.

In September 1931, the Simpson Brothers of Boston began building the abutments, pylons, and piers, completing this substructure work in January 1932. The McClintic-Mitchell Construction Company—a prominent bridge-building firm from Pittsburgh—began erecting the superstructure in April, and joined the Gil and Erving sides of the bridge on July 2, 1932. Decorative Art-Deco stepped concrete pylons rise on either side of each end of the bridge to form attractive entrance portals. Neoclassical cast-iron lampposts with paired electric lights and crowned with decorative eagles sit atop the pylons, and a decorative iron fence runs along the length of each side of the bridge.

Local residents and state officials dedicated the bridge on September 10, 1932, with an audience of nearly 15,000. During the lean years of the Great Depression, the bridge served the community not only as a source of employment, but also offered an optimistic symbol of progress. Shortly after the dedication, the American Institute of Steel Construction gave the French King Bridge its Annual Award of Merit for the most beautiful steel bridge.

The bridge’s name refers to a local landmark—the French King Rock— located just upstream. According to local legend, during the French and Indian Wars, a French officer scouting along the river named the landmark for his regent. Many businesses in the nearby towns also use the French King name.

The French King Bridge heralded the onset of a new automobile age, in which cars would come to reshape the fabric of communities and instigate large-scale infrastructure projects. It also proclaimed that modern technology could impose its will upon the environment; roads no longer had to follow rivers, but could span the most difficult crossings.

While the French King Bridge brought tourism to the region, it also diverted traffic away from Millers Falls and Turners Falls. Moreover, thirty years after the French King Bridge’s construction, new federal interstates were completed that obviated the need for U.S. Route 2. The more southerly I-90 became the major east-west conduit in the state, relegating U.S. Route 2 and the Mohawk Trail to the status of scenic byways. Regardless, the French King Bridge endures as an icon of engineering talent and marks the ascendency of the automobile in American life.

References

Bennett, Lola. “French King Bridge (MA-100),” Franklin County, Massachusetts. Historic American Engineering Record, 1990. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Campanile, Robert. The Mohawk Trail. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2007.

Roper, S. J. “Massachusetts Historic Bridge Inventory – French King Bridge (ERV.904/GIL.900),” Erving/Gill, MA, February 1988.