Glen Echo Park, first developed as a residential community by Edward and Edwin Baltzley, combines a bucolic natural landscape with an eclectic mix of late-nineteenth-century and early- to mid-twentieth-century buildings that reflect changing trends in educational, recreational, and amusement activities. Its alluring landscape, perched on a verdant bluff overlooking the Potomac River, has captured the imagination of Washingtonians for over a century. In that time, Glen Echo evolved from a suburban retreat to Chautauqua, to trolley line amusement park, to national park, remnants of which are all still embedded in the landscape.

Glen Echo’s heyday came in 1911 when it was developed as an amusement park for the trolley line linking Washington with its outlying suburbs. Such end-of-the-line attractions were fairly common, crediting trolley companies with the development of the amusement park as an American institution. Parks such as Glen Echo, among the few surviving, were enabled by a national increase in leisure time and disposable income and the rise of thrill-seeking rides. Conversely, post-World War II changes in entertainment trends contributed to their decline. Glen Echo ceased operation in 1968 following civil rights protests challenging its racial segregation. It was transferred to the National Park Service in 1970 and now operates as a recreation and arts center.

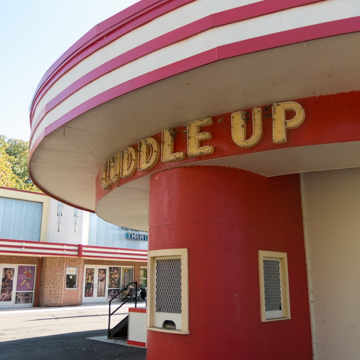

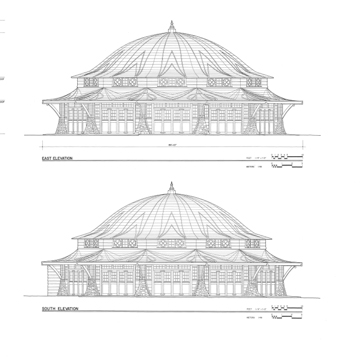

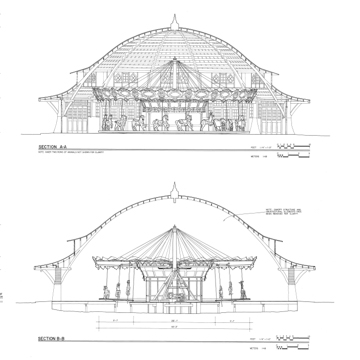

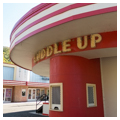

The park preserves many of the iconic features of amusement parks and other reminders of its early days. The Chautauqua’s stone tower designed by Victor Mindeleff as a grand entrance still stands, as does the trolley’s “Yellow [car] Barn.” Also extant is the streamlined entrance canopy designed by Philadelphia architect Edward Schoeppe, the penny arcade, shooting gallery, popcorn concession, and bumper car and “Cuddle Up” rides. The only operational ride is the rare surviving 1922 carousel manufactured by the William H. Dentzel Company of Philadelphia. It is housed within a Shingle Style pavilion with a dual-pitched bell-shaped roof and contains fifty-two carved wooden animals created by one of the nation’s most skilled carousel carvers, Daniel C. Muller. Also functioning is its Wurlitzer 165 Military Band organ.

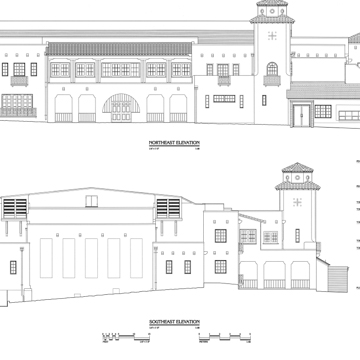

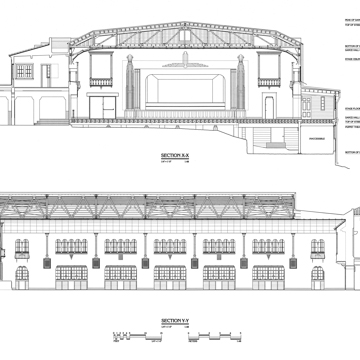

A park anchor is the 1933 Spanish Ballroom, also designed by Schoeppe. Fueled by Big Band, swing, and jazz music, dance halls became all the rage between the two World Wars. They represented the democratization of dances originally the domain of debutante and society balls. Spanish-influenced elements include a stuccoed facade, faux vigas, and a tile roof, along with Art Deco zigzagged balustrades and pylons. The two-story ballroom includes a mezzanine-level viewing promenade. Patrons danced to live music performed by Dave McWilliams and his orchestra, and other celebrity Big Band and jazz ensembles. A year-round dance season still draws crowds.

References

Adams, Judith A. The American Amusement Park Industry: A History of Technology and Thrills. Edited by Edwin J. Perkins. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1991.

“Dentzel Carousel and Building,” Montgomery County, Maryland. Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1994. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. MD-1080-A).

Kyriazi, Gary. The Great American Amusement Parks. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press, 1976.

Price, Virginia, “Glen Echo Park, Spanish Ballroom,” Montgomery County, Maryland. Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1997. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. MD-1080-B).

Samuelson, Dale. American Amusement Parks. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBJ Publications, 2001.

“Schloss Ballroom Advances.” Billboard 45, no. 16 (April 1933): 30.

Scott, Gary, “Glen Echo Amusement Park (Glen Echo Historic District),” Montgomery County, Maryland. National Register of Historic Places Inventory–Nomination Form, 1984. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Scott, Gary, and Nicholas Veloz. “Carrousel at Glen Echo Park,” Montgomery County, Maryland. National Register of Historic Places Inventory–Nomination Form, 1980. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Unrau, Harlan D. “Glen Echo Park, George Washington Memorial Parkway, Maryland,” Historic Structure Report. March 1987. Compiled for, and under the auspices of, the U.S. Department of Interior, National Park Service, Denver Service Center, Eastern Team.

Wyrauch. “Glen Echo on the Potomac.” Interviews for film, Glen Echo Park, Glen Echo, Maryland, 1992.