You are here

Acoma Pueblo

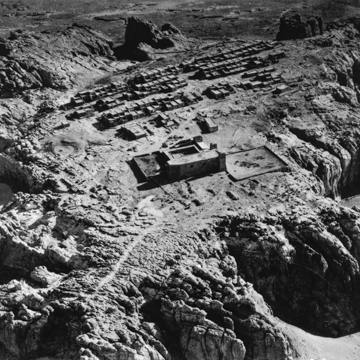

The walls of Acoma Pueblo rise atop the dramatic planes of its isolated sandstone mesa. Inhabited since at least 1200 CE, it is one of the oldest continually occupied towns in the United States. While Acoma has undergone alterations, its present layout and design have mid-seventeenth-century origins. Today, the pueblo is the ceremonial center of the Keres-speaking Acoma people, as well an icon of New Mexico for tourists.

The core arrangement of Acoma’s streets, plazas, and housing blocks dates to the Spanish Colonial period. Rebuilding and infill have altered the layout, while renovations have integrated modern materials such as manufactured windows, cement stucco, and ground-level doorways into the town’s older fabric. The result is a collage of materials and forms that documents both centuries of adaptation, and an enduring commitment to a place central to Acoma identity.

Tribal origin accounts describe the emergence of Acoma’s ancestors from the underworld, migrating south to seek a home foretold to them. Arriving at Acoma Mesa and hearing their shouts of “ha’ako” (“the prepared place”) echoing clearly back, they moved to the top of the mesa. Its steep, 350-foot cliffs provided natural security, but presented logistical challenges as the Acoma carried building supplies up steep trails from below, and collected rain water in mesa-top cisterns.

Archaeological evidence indicates that Acoma’s ancestors occupied a large territory from the Rio Grande to El Morro in the west. In addition to an ancient Indigenous group, others arrived to join the developing cultural area, possibly from the Mesa Verde and Cebollita Mesa regions. Based on ceramic finds from 1951–1952 excavations, the move up to Acoma Mesa took place between 1150 and 1200.

Spanish explorers in Coronado’s expedition first saw Acoma in 1540, noting its interconnected housing blocks three to four stories high, ceremonial chambers (kivas), large cisterns, stores of maize, and easily defended location. They returned under Juan de Oñate to colonize Acoma in 1598–1599. As their initial, guarded interactions deteriorated, the Spanish retaliated for the killing of several soldiers by capturing the mesa, burning the town, and killing 600 to 800 people. Oñate brutally punished the surviving captives: 70 men and 500 women and children. Men and women were condemned to twenty years of slavery, and males over twenty had one foot amputated, while boys under twelve were made servants of Spanish colonists, and girls were given to Franciscans missionaries to raise.

Preliminary excavations of a pre-Hispanic housing block northeast of the mission show some evidence of Acoma’s early architecture and destruction by fire. Incomplete because later generations reused their materials, these ruins combined sandstone and puddled adobe walls, with traces of plaster and red and white paint. Slab-lined rectangular firepits were sunk in the floors alongside ash receptacles, and possible traces of ladder footings hinted at rooftop entryways.

Survivors of the Spanish retaliation rebuilt the village. In 1629, Fray Juan Ramírez was assigned to Acoma as its resident missionary priest and directed the construction of a mission over the ruined pre-Hispanic structures. Oral histories and archaeological tests indicate that in the seventeenth century the original settlement on the south end of the mesa moved to its present site on the north side. Adobes in the lower levels of the houses are similar to those from the mission, suggesting roughly contemporaneous construction, while tree ring studies demonstrate that roof construction in the northern housing blocks began in the late summer of 1646. Builders started with lower level rooms on the north side, adding room blocks to the south and upper floors until completion around 1652.

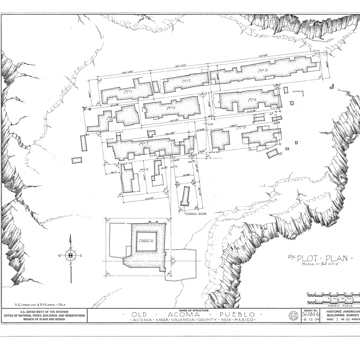

Acoma’s mid-seventeenth-century reconstruction is coherent and remains visible to this day. The housing blocks are arranged in three rows running east-west, with parallel streets in between and narrow north-south alleyways dividing each block. As a matriarchal society, Acoma women own the individual houses, which are multistory groups of aligned rooms transecting their blocks like row houses. The regularity of Acoma’s plan and the burst of construction indicated by tree ring dates are unusual among colonial-era pueblos and strongly suggest a centralized planning process or directing authority during reconstruction. Possibly the pueblo’s government had recovered from the Spanish assault and was sufficiently organized to direct a major building episode by the 1640s. Alternatively, a resident missionary may have filled this role, although it is unknown if a friar was assigned to Acoma during this period.

These adobe housing blocks required frequent repair, especially in the more exposed upper floors. Despite this organic process of alteration, and the introduction of more recent structures, the buildings retain their core adobe walls. Resting on rubble foundations set on mesa bedrock, they are built from the molded adobe bricks introduced by the Spanish, with adobe mortar and protective coats of mud plaster. The continuous side or party walls were subdivided into rooms by unbonded interior partitions. The houses had efficient solar exposure, with upper rooms on the southern side set back to create flat rooftop terraces where people worked during pleasant weather. The party walls were stepped to provide privacy, shelter from the wind, and stairs to upper roof levels. The high northern walls blocked the elements and shaded the streets.

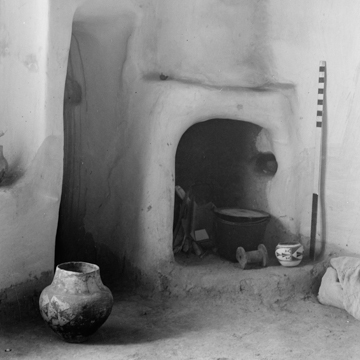

Originally, the housing blocks had no ground-level doorways; residents climbed ladders to rooftops and descended through hatchways into the interiors. The flat ceilings of storage rooms below formed the floors of terraces and living quarters above. The roofs and floors were constructed from round pine beams (vigas), supporting layers of latillas, vegetal matting, and compacted earth. Vigas were typically six inches or less in diameter, running north-south and extending two or three feet from the southern wall to support stone parapets across upper terraces. These projections shaded the lower walls and reduced heat during the summer. Light entered through rooftop hatches and small windows made from thin panes of translucent gypsum (selenite). Wooden trap doors and hatchways provided access between floors. The rooms had small corner fireplaces of adobe for heat, often with old pots forming the upper chimney flue. Built-in furniture included multipurpose adobe benches and corn grinding bins. Chutes in the walls facilitated easy movement of dried foodstuffs from the rooftops to storage rooms, while bins within the walls could be sealed with plaster for long-term storage.

Acoma incorporates a number of civil and religious spaces among its housing blocks. The main plaza is a wide cross-axial street through the center of town. It is the focus of dances and cultural observations, such as the Feast of Saint Esteban, when community members construct a cottonwood and maize bower to shelter the patron saint. A bench in the northeast corner of the plaza provides honored seating for tribal officials, while onlookers watch from the plaza’s edges and nearby rooftops. In contrast to the plaza’s open, public nature, Acoma’s kivas are restricted ceremonial chambers. They are rectangular, above ground, and integrated into architectural blocks, unlike the round, semi-subterranean kivas of Rio Grande pueblos. There are seven main kivas at Acoma, recognizable by windowless facades and large three-pole ladders leading to rooftop entryways.

The strain put on pueblo resources by the Spanish civil and religious authorities, along with the suppression of their Indigenous religion, inspired sporadic resistance that culminated in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680–1692, when tribes united to expel the Spanish colonizers from New Mexico. Acoma participated by killing its resident priest but left the mission largely intact, and by 1699 a missionary had returned to the mesa. New Mexico passed to Mexican rule in 1821, and then to U.S. control in 1847–1848, but the pueblo’s built environment remained unchanged until the arrival of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway in 1880–1881. Cutting through Acoma territory, the railroad introduced industrial materials such as milled lumber, manufactured doors, glazed windows, and commercial paints. A growing population, tourist market, and interaction with outsiders also contributed to the pueblo’s changing architecture.

The Historic American Building Survey of 1934 documented the pueblo in extensive photographs and drawings. New houses began filling in the spaces between earlier structures and the open areas to the south and east. As glass and lumber became available, factory-made “barn sashes” with regular arrangements of four or six glass panes replaced selenite, and prefabricated doors were inserted into ground-level walls. With improved lighting and circulation, first-floor spaces increasingly became primary living rooms, and upper floors were reworked or deteriorated.

The pueblo has continued to evolve since then. An existing trail up the mesa was widened in the 1950s for the filming of a motion picture. Milled lumber framing, cinder block, pressed adobe brick, cement mortar, and stucco now predominate, while metal stovepipes, manufactured roofing, and rain gutters mark the flat rooflines. Portable toilets provide necessary facilities, and some houses have generators and bottled gas for heating. The last quarter of the twentieth century saw intensive rehabilitation of early houses under the auspices of the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Acoma remains the symbolic center for its people, though most now live in the nearby towns of Acomita and McCartys, which offer greater economic opportunities and the conveniences of running water, electricity, and sewage. Families retain their houses on the mesa, however, returning for religious and communal observances. Tribal leaders select a small group of individuals to reside full time in Acoma each year, along with a few who do so out of choice.

Acoma Pueblo documents a history of change and continuity. Together with the San Esteban Mission and the 2006 Sky City Cultural Center and Haak’u Museum, it comprises an exceptional architectural assemblage spanning nearly four hundred years. With its relative proximity to Albuquerque and railroad depots, Acoma has long been a destination for such visitors as the effusive journalist Charles F. Lummis, whose romantic evocation of “the most wonderful aboriginal city on earth, cliff built, cloud swept, matchless Acoma” would be echoed nearly a century later in Vincent Scully’s Pueblo: Mountain, Village, Dance. Modern scholars have appreciated the pueblo’s Indigenous form and its integration into its larger landscape; sharing it with respectful visitors remains important to Acoma’s people, whose tourism program was among the first by a Native American tribe.

Tours of the pueblo leave daily from the Sky City Cultural Center.

References

Dittert, Alfred E., Jr. "Culture Change in the Cebolleta Mesa Region, Central Western New Mexico." Ph.d. dissertation, University of Arizona, 1959.

Garcia-Mason, Velma. “Acoma Pueblo.” In Handbook of North American Indians: Volume 9, Southwest, edited by Alfonso Ortiz, 450-466. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1979.

Lummis, Charles F. The Land of Poco Tiempo. New York: Charles Scriber’s Sons, 1893.

McHenry, Paul G., Jr. “Rebuilding Ácoma Sky City.” APT Bulletin 22, no. 3 (1990): 55-64.

Minge, Ward Alan. Acoma: Pueblo in the Sky. Rev. ed. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2002.

Nabakov, Peter. Architecture of Acoma Pueblo: The 1934 Historic American Buildings Survey Project. Santa Fe: Ancient City Press, 1986.

Playdon, Dennis G., and Brian D. Vallo. “Restoring Acoma: The Pueblo Revitalization Project.” Cultural Resource Management 23, no. 9 (2000): 20-24.

Robinson, John Kelly. "Phoenix on the Mesa: Acoma Pueblo during the Spanish Colonial Period, 1500-1821." Ph.d. dissertation, Oklahoma State University, 1997.

Robison, William J. “Tree-Ring Studies of the Pueblo de Acoma.” Historical Archaeology 24, no. 3 (1990): 99-106.

Ruppé, Reynold J., Jr. The Acoma Culture Province: An Archaeological Concept. New York: Garland Publishing, 1990.

Ruppé, Reynold J., Jr., and Alfred E. Dittert, Jr. “The Archaeology of Cebolleta Mesa and Acoma Pueblo: A Preliminary Report Based on Further Investigation.” El Palacio 59, no. 7 (July 1952): 191-217.

Scully, Vincent. Pueblo: Mountain, Village, Dance. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Sky City Cultural Center and Haak’u Museum. “History of Acoma Pueblo.” Accessed October 24, 2015. http://www.acomaskycity.org.

Vieth, Catherine deJarnette. "Moving Off the Mesa: A Typological Analysis of Housing at Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico." Master’s thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 2001.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.