The Baca/Dlo’ay azhi Community School at Prewitt in the southeastern part of the Navajo Reservation represents three historic phases of federal educational architecture for Native Americans. The earliest buildings (1935) draw on the Pueblo-Spanish Revival and the Diné (Navajo) hogan to create a design rooted in the regional vernacular of New Mexico. After World War II, the number of Native American students dramatically increased and the school became one of dozens across the Navajo Reservation that were either constructed anew or expanded with trailers and Quonset huts. At the turn of the century, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) embarked on a new program to modernize schools on the Navajo Reservation. As part of this program, Diné architect Dyron Murphy was commissioned to design a $12.3 million facility that incorporated Diné cultural traditions and ecologically sustainable building practices.

During the late 1920s, criticism of the Office of Indian Affairs (the predecessor to the BIA) inspired efforts to improve Native American education. A report issued by the Meriam Commission in 1928 described the condition of federal Indian boarding schools in alarming detail, and provided conclusive evidence of malnutrition, long absences from home, and a curriculum that stressed housekeeping and other types of student labor. The Diné were particularly affected by the boarding school system because of the wide dispersal of Diné households across the Navajo Reservation, the largest reservation in the U.S.

In 1933, the Roosevelt administration employed the New York architectural firm of Mayers, Murray and Phillip (MMP) to design buildings for Native American reservations across the United States. MMP included three former members of Bertram Goodhue's studio. Their work for the Roosevelt administration resulted in hundreds of new buildings and established a federal presence in some of the most remote areas of the Navajo Reservation.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s new Indian Commissioner, John Collier, oversaw the construction of 46 non-residential day schools on the Navajo Reservation, enabling more students to live with their families. MMP’s design for the schools followed Collier’s dictum that reservation buildings should embrace regional architectural traditions. The basic scheme included a single-story, Pueblo-Spanish Revival building that combined classrooms, a teacher’s residence, and a garage/utility area. Many of the schools on the Navajo Reservation also included Diné hogans designed by MMP. The hogans were originally intended to be used as home economics classrooms, clinics, and staff residences.

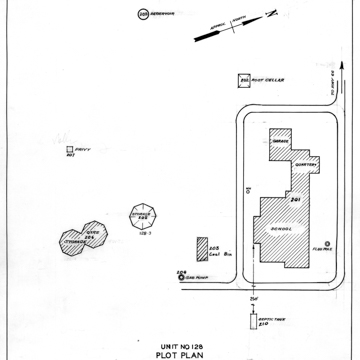

The Baca/Dlo’ay azhi (dlo’ay azhi means “little prairie dog”) school retains all of the major architecture completed between 1935 and 1942. These include a main building with two classrooms, kitchen, dining room, teacher’s residence, and garage/utility area; a hogan; a double-hogan; a coal shed; a pump house, and an octagonal cistern for the school’s water system. All six of these buildings were constructed from native sandstone by the Civilian Conservation Corps-Indian Department (CCC-ID), a special group within the CCC organized specifically to meet the needs of Native American workers.

After World War II, the federal government was unable to provide space to accommodate the number of school-age Diné children. This problem was addressed by the introduction of “trailer schools” in Navajoland, which could be constructed cheaply and quickly. The BIA built 36 new trailer schools during the early 1950s, while increasing the capacity of existing schools at the same time. The mid-century metal trailer and Quonset huts located on the south side of the Baca/Dlo’ay azhi Community School represent rare survivors from this period of educational architecture on the Navajo Reservation.

The latest construction phase at the school includes a 79,000-square-foot facility designed by Murphy. The building, located to the north of the oldest part of the school, follows the traditional Diné model of cultural planning and emphasizes the four cardinal directions. The main entrance faces east toward the sunrise, following the pattern of Diné hogans. The classrooms are arrayed along the south side, the direction associated with youth and activity. The communal areas of the school, including the kitchen, dining room, and gymnasium are located to the west, which is associated with the day’s end and the time when families come together. According to Diné cosmology, the north is connected with tribal elders. Murphy located the school’s administration area to the north, and arranged it in concentric sections inspired by feathers.

The school has a circular core that includes the main circulation route surrounding the library. At the center of the library is a canopy decorated with images of the Four Sacred Mountains of the Diné, which supports an octagonal roof emulating the roof of a hogan. A skylight connects the school with the fifth, upward direction, while a sunken area in the library floor integrates the building with the earth and relates it to the sixth, downward direction. The exterior of the building is ornamented with corn motifs and is landscaped with indigenous plantings. Murphy’s design revealed the parallels between traditional Diné cultural planning and the principles of sustainable building. In 2003, the Baca/Dlo’ay azhi Community School became New Mexico’s first LEED-certified building and the first LEED-certified building constructed by the U.S. Department of the Interior.

The Baca/Dlo’ay azhi Community School is not open to visitors but is visible from I-40 and from NM 122 and NM 412.

References

Gray, Autumn. “BIA School in Prewitt is Bright and Green.” Albuquerque Journal,April 22, 2004.

Murphy, Dyron. Personal communication, December 21, 2015.

Young, Robert W. The Navajo Yearbook of Planning in Action.Report No. IV, 1954. Window Rock: Navajo Agency, 1955.