You are here

Zuni Pueblo

Zunis have occupied the site that they call Halona:wa/Idiwana, “the middle place,” for at least 700 years, flexibly adapting their ways of building while preserving critical components of the town’s fabric in a continuous practice of tradition and change. Today Zuni Pueblo is a modern town that incorporates industrial materials and dispersed suburban living, but remains a remarkably stable, culturally coherent community.

Rugged sandstone mesas surround the town on a low knoll north of the Zuni River. Today, 12,000 Zuni people live mostly within a three-mile radius of the pueblo and in nearby Blackrock, with New Mexico 53 connecting the communities. Originally, the town’s housing blocks of aggregated stone and adobe focused inward around two square plazas. Even as its buildings have evolved through time, Zuni Pueblo has retained its traditional pattern of plazas and ceremonial routes. This layout is integral to Zuni religious practices and persists despite the effects both of Spanish missionary activity starting in the 1600s and subsequent expansion, which led to greater openness between structures and the use of modern building materials.

Zuni oral histories describe their ancestors’ arrival in this place after emerging from the underworld in the Grand Canyon, from where they traveled in search of a home at the center of the cosmos. They eventually settled at Zuni Pueblo when a giant water strider placed a foot in each of four world oceans, spreading out to the cardinal points while its body located the pueblo at the middle place.

Anthropologists identify the Zuni language as a linguistic isolate, with no discernably related languages. Ancestral Zuni speakers have probably maintained a distinct linguistic community for at least 7,000 to 8,000 years, without any major groups splitting off to form related languages. Archaeologists believe that today’s Zuni people were brought together by multiple migrations of ancestors. By 1400, they lived in large, stable pueblos along the Zuni River Valley, of which six or seven towns existed in the sixteenth century. Historically, their descendants practiced a system of land use divided between core residential areas, farmlands along the river valley, and larger surrounding regions for hunting, collecting plants and minerals, and (later) grazing. Zunis spent much of the year dispersed in small farming villages and congregated in town during the winter months.

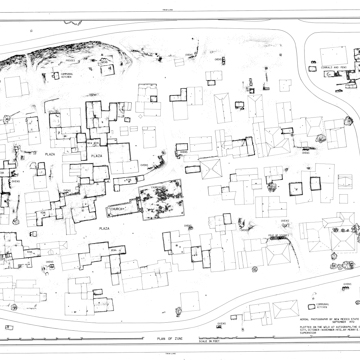

Present-day Zuni Pueblo spreads over the sites of two pre-Hispanic towns, which archaeologists label Halona:wa North and South. Halona:wa South was a fairly large pueblo on the south bank of the Zuni River. The anthropologist Frank Hamilton Cushing partially excavated it in 1888, uncovering a rectangular settlement beneath Halona Plaza with an estimated 375 rooms dating circa 1250 to 1350. Halona:wa North, or the “Middle Village,” stood on the opposite side of the river and comprised two square plazas at the crest of the knoll, with surrounding room blocks of sandstone masonry. Ceramics and tree-ring chronology date its occupation to the mid-1300s.

The Spanish first visited Zuni with Vázquez de Coronado in 1540, but contact was sporadic until Franciscans established a mission in 1629. By the mid-seventeenth century, its substantial single-nave adobe church and attached residency ( convento) were built on the southeast slope of the Halona:wa North mound. It was destroyed during the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, when Zunis joined other pueblos in overthrowing Spanish rule. For security, the Zuni towns congregated on top of Dowa Yalanne Mesa, forging their identity as a single community. After the Spanish reconquest of New Mexico in 1692, Zunis remained upon the mesa until 1699, when they returned to settle together around the Halona:wa North site, which became Zuni Pueblo. The aggregation of their formerly distinct towns substantially increased the pueblo’s population, expanding its housing blocks around the site of the mission and creating a new, elongated plaza. During the eighteenth century, frequent raids by Apaches and Navajos improved relations among Spanish and Zunis in the shared interest of defense.

Zuni’s population fluctuated between 1,500-2,000 residents, making it the largest of the pueblos. Buffered by its distance from Spanish settlements, the Zunis avoided confrontation, adopting useful aspects of European culture while resisting others. After Spanish rule ended with Mexican independence in 1821, Zuni was left without a resident priest for most of the nineteenth century. Following the occupation of New Mexico by the United States in 1846–1848, reservation boundaries for Zuni were established in 1877 and an Indian agent appointed to manage external affairs as encroachments by non-Zunis increased.

In the late nineteenth century, archaeologists and anthropologists began to take an interest in Zuni Pueblo. The brothers Victor and Cosmo Mindeleff conducted an architectural survey in 1881, documenting a large complex focused on two small, roughly square dance plazas and surrounded by housing blocks with rooftop terraces. Because these blocks grew organically through additions on top or at the edges of existing houses, lower-level roofs became terraces and floors for upper-level rooms as two- or three-story houses inclined upward to create as many as five terrace levels. The terraces extended south and east, benefiting from passive solar energy while higher walls to the north and west shielded them from prevailing winds.

The seven housing blocks contained hundreds of rooms, with narrow alleyways at ground level. Many household functions occurred on the semi-public rooftop terraces. The ground level rooms originally had few doorways or windows, and ladders provided access to terraces and interiors. Houses were entered through rooftop hatchways with raised curbing and slab closures. As the risk of Navajo and Apache raids declined in the later nineteenth century, residents incorporated windows and doors in lower rooms, and the desirable spaces shifted to the more easily accessible ground floor. Still, raised ladders remained a prominent feature of the pueblo’s sky line.

Zuni is a matrilineal and matrilocal society, in which women traditionally owned the houses and played a major role in constructing them. They added and renovated rooms as needed, maintaining the larger community’s materials and ways of building but introducing subtle variations. Older houses had sandstone walls, while adobe bricks predominated after the Pueblo Revolt. Rounded vigas supported willow, split wood, or brush matting with packed earth and clay to seal the flat roofs. Viga ends projected to hold parapets, sandstone copings, and drainspouts protecting mud-plastered walls from rainwater. They required regular replastering with mud, shared work that both helped to integrate Zuni society and unified the town’s changing architectural forms.

Houses had whitewashed interiors, earthen or slab-paved floors, and storage alcoves in the walls. Cool, dark cells in the lower floors provided food storage, and families with religious responsibilities might also have a room designated for storing ritual objects. Many activities took place in multipurpose living spaces, with adobe benches lining the walls for storage and sleeping. Hearths were against corners or short spur walls, with mud-plastered hoods funneling smoke to chimneys of interlocking broken pots stacked on masonry substructures. These directed smoke above the rooftop terraces.

Ceremonial and religious factors determined the pueblo’s layout, with dance plazas as the locus of public religious observations, when spectators gathered on surrounding rooftops. Pathways connecting the plazas with each other and the outskirts of town form processional routes for religious events. Zuni had six rectangular kivas integrated into housing blocks around the plazas, while large structures served as clan houses and meeting rooms for medicine societies. Annual Sha’lak’o ceremonies in early December have had a notable impact on domestic architecture. Six to eight households host a Sha’lak’o deity every year as houses are renovated and enlarged for the ceremonies: an estimated 600-700 renovations occurred between 1880 and 1980. Generating significant changes over time, this custom ensures that Zuni architecture is never static.

The population of Zuni more than quadrupled in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, while the railroad’s arrival at Gallup in 1881 brought increased economic engagement and such manufactured building materials as milled lumber, prefabricated doors, and glass windows. As Indian raids decreased, the town opened up, upper stories were gradually disassembled, and many households moved to suburbs on the margins of town and south of the river.

When Alfred Kroeber resurveyed Zuni in 1915, he noted both the rapid transformation of individual structures and the conservation of the pueblo’s general spatial form. As the pueblo spread outward, new houses reused old materials and continued to face towards the Middle Village, with families building contiguously to the areas where they had traditionally lived. Zuni retained its centralized focus, the outlines of major plazas, and its ceremonial pathways. Almost all of the housing blocks were replaced by single-story houses above the filled remnants of aggregated house blocks.

In the early twentieth century, the Zunis adopted the use of ashlar masonry from outside initiatives such as the Blackrock Dam (1908) and Saint Anthony’s Catholic Mission (1922–1923). They made this construction method their own, with close-fit, purplish-red sandstone blocks, finely mortared joints, arched openings, and no exterior plaster. Early structures retained the traditional rooftop terraces, but builders soon incorporated pitched roofs, and ladders disappeared except for kivas. Only houses around the plazas retained flat terraces as public viewing spaces for ceremonies and dances.

As use of automobiles increased, roads were paved, alleyways widened, and open ground became parking. Most Zunis resided full time in the pueblo and seasonal mobility declined as vehicles improved access to outlying farms and sheep camps. New Mexico 53 became the primary route through Zuni, its “Main Street” where commercial establishments catering to motorists were located along with such public structures as the A:shwi Tribal Offices Building (1970) and the Visitor Center.

Utility modernization began in the twentieth century, with electric hookup in 1950 and two deep wells providing water to faucets by 1954. Sewage followed in 1961, and all of Middle Village had water by 1980. With the introduction of utilities, domestic interiors became more specialized, separating kitchens, bedrooms, living spaces, and bathrooms. Using Federal Housing and Urban Development (HUD) funding, the Zuni Housing Authority constructed frame houses. Other structures incorporated such industrial materials as concrete blocks in an extension of the town’s long history of masonry construction. Often building in an additive, vernacular manner, the pueblo maintained its traditional aesthetics.

Zuni Pueblo was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975. Recent decades have seen concerted efforts to preserve the pueblo’s historic character and appearance, while recognizing the changes in construction and housing brought by modernization. Rather than privilege the picturesque terraced housing blocks at the expense of later one-story houses, the pueblo’s spatial form and the scale of its inner courtyards, alleyways, and rooftop setbacks around the plazas are prioritized. New construction is matched to existing plans, walls, and materials, while retaining as much historic fabric as possible. The Zuni Archaeology Program and Zuni Cultural Resources Enterprise have documented Middle Village structures, and outside organizations have collaborated to restore the historic trading post as the A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center.

Zuni Pueblo welcomes respectful visitors, who should check in at the Visitor Center for an orientation, tour schedule, and photography permits.

References

Bunting, Bainbridge. Early Architecture in New Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1976.

Crampton, C. Gregory. The Zunis of Cibola. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1979.

Damp, Jonathan E. Archaeological Treatment Plan for Architectural Renovations within the Middle Village of Zuni Pueblo. Zuni, NM: Zuni Cultural Resource Enterprise, 1998.

Ferguson, T. J. Historic Zuni Architecture and Society: An Archaeological Application of Space Syntax. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1996.

Ferguson, T. J. “Zuni Traditional History and Cultural Geography.” In Zuni Origins: Toward a New Synthesis of Southwestern Archaeology, edited by David A. Gregory and David R. Wilcox, 377-403. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2007.

Ferguson, T. J., and Barbara J. Mills. Archaeological Investigations at Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico, 1977-1980. ZAP Report No. 183. Zuni Pueblo: Zuni Archaeological Program, 1982.

Ferguson, T. J., and E. Richard Hart. A Zuni Atlas. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990.

Hart, E. Richard, ed. Zuni and the Courts: A Struggle for Sovereign Land Rights. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995.

Hill, Jane H. “The Zuni Language in Southwestern Areal Context.” In Zuni Origins: Toward a New Synthesis of Southwestern Archaeology, edited by David A. Gregory and David R. Wilcox, 22-38. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2007.

Kintigh, Keith W. Settlement, Subsistence, and Society in Late Zuni Prehistory. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1985.

Kroeber, A. L. Zuñi Kin and Clan. New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1917.

Mindeleff, Victor. A Study of Pueblo Architecture in Tusayan and Cibola. 1891. Reprint, Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989.

Nabakov, Peter, and Robert Easton. Native American Architecture. 1989. Reprint, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.