Chaco Culture National Historical Park contains one of the most important, complex, and monumental Pre-Columbian landscapes in North America.

It also remains one of the most mysterious. Because the people who built Chaco left no written record of who they were, where they came from, and where they went after their civilization collapsed circa 1300, they have remained subjects of continuing debate and competing interpretations ever since the site was first explored by archaeologists in the nineteenth century. As the writer Kendrick Frazier has noted, “We know them by their works… [and] can only speculate about key elements of their lives.” Earlier archaeologists called them Anasazi, using a Navajo word, and they are now identified variously as Ancient Pueblo Peoples or Ancestral Puebloans by those who accept the claims made by the historic Pueblos of New Mexico that they are descended from the builders of Chaco. For those who think the identity of their descendants, let alone their origin, remains an open question, they are known more neutrally as Unknown Native Americans.

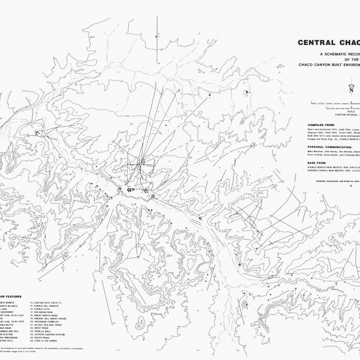

The core of the park is located in Chaco Canyon and extends for six miles along Chaco Wash. The hub of an empire that reached its peak between the mid-ninth and the mid-twelfth centuries, Chaco Canyon is filled with a dense network of monumental structures that includes Chacoan great houses, great kivas, mounds, pyramids, ramps, and stairways, as well as “small houses” and other built features. This network was connected by a remarkable “linescape,” a system of alignments and excavated roadbeds that extended to outlying settlements. Remains of the Chacoan culture are scattered across an area of over 60,000 square miles in the Four Corners region of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Colorado. Because of its significance, it was designated a National Monument in 1907 and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987.

Chaco Canyon has been the object of archaeological investigations ever since Richard and Clayton Wetherill began, with the Harvard archaeologist George Pepper, the earliest formal excavations for the Hyde Exploring Expedition in 1896. Organizations including the American Museum of Natural History, the Smithsonian Institution, and Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology have sponsored fieldwork in the canyon and collected artifacts. Pepper’s Pueblo Bonito, documenting the Hyde Exploring Expedition (1896–1900), and both The Material Culture of Pueblo Bonito and The Architecture of Pueblo Bonito, documenting the work of Neil Judd for the National Geographic Society (1921–1927), provide the basis for most subsequent interpretations. In addition to the origins of the Chacoan people, also unknown are their social, religious, and political organizations, the observed coordination of their architecture with celestial phenomena and terrestrial landforms, their possible connections with other Mesoamerican cultures, and the factors that contributed to the abandonment of Chaco Canyon circa 1150 CE.

The architecture of Chaco Canyon forms an integrated landscape that was planned and then constructed over several centuries in multiple phases. The scale and significance of the site may be inferred from the estimated 225,000 trees that were transported at least forty miles to build it. Archaeologists have located about two hundred outlying settlements in the Four Corners region dating from between 400 and 1300 CE. Rapid population growth in the ninth century led to a dramatic increase in construction that peaked between 850 and 1100.

The settlements were typically focused on a community great house with a great kiva. A community great house is a multi-room, multistory structure with massive rubble-core masonry walls generally three feet wide at the base. Community great houses often enclose several large, round rooms known as kivas, each within a square envelope. A great kiva—a circular, largely subterranean structure with masonry walls and a four-post roof system—is usually located in the vicinity of a community great house and probably served as a communal lodge. Great kivas range in size from 33 to 75 feet, with the largest at Peñasco Blanco.

Peñasco Blanco is one of twenty first-order Chacoan great houses. The majority of the first-order great houses are located in “Downtown Chaco”; Pueblo Bonito, Chetro Ketl, Pueblo del Arroyo, Pueblo Alto, and the isolated great kiva known as Casa Rinconada lie within a half-mile of each other. First-order great houses are also found along the Animas and San Juan Rivers in northwest New Mexico—three at Aztec Ruins National Monument and another at Salmon Ruins in Bloomfield, New Mexico.

Significantly larger than community great houses, first-order great houses are primarily located along the north side of Chaco Canyon, and usually have great kivas within or adjacent to a large enclosed plaza. Planned in coordination with the cardinal directions, the great houses typically face south across their plazas. The solar and lunar cycles (and perhaps other celestial phenomena) are related to individual building elements and to alignments between buildings. For example, the south wall of Pueblo Bonito aligns with the rising sun on the solar equinoxes.

In their fully developed form, the room blocks of these great houses tended to be laid out in uniform rectangular units aligned to form galleries. Archaeologists at first thought that first-order great houses like Pueblo Bonito were simply larger versions of community great houses, yet otherwise analogous. The absence of fire hearths and other signs of domestic inhabitation at Pueblo Bonito has led to speculation in more recent scholarship that the great house might have served ritual purposes as monumental instruments of ideological, religious, and political power.

Chaco Canyon was part of a large trade network, and artifacts have been excavated that originated from points as far as 1,200 miles to the south: pottery from southern Arizona; seashells from the Gulf of Mexico, the southern California coast, and the Gulf of California; and macaws, parrots, and copper bells from central Mexico. Over 50,000 pieces of turquoise have been found in the walls of Pueblo Bonito, which is more than four times the amount of turquoise recorded at all other prehistoric Southwestern archaeological sites combined. Recent research has substantiated that cylinder jars excavated from Pueblo Bonito once held cacao probably grown in Central America, and the jars resemble cups used by the Maya to drink chocolate. Perhaps the most compelling architectural evidence of a Chacoan connection with ancient Mesoamerica is Chetro Ketl’s “colonnade,” thirteen masonry piers that resemble structures found at Tula and at Chichen Itzá.

The Chacoan landscape contains numerous other features, in addition to the houses and kivas. These include platforms and conical mounds of earth, like the paired platform mounds on the south side of Pueblo Bonito; each measures approximately 2,500 square feet in area and ranges from between 10 and 13 feet high. The ruins of at least two monumental pyramids appear to have been partially shaped from existing hills on the south side of Chaco Canyon.

About 700 feet to the east of Chetro Ketl is Chetro Ketl Field. Measuring approximately 400 x 460 feet and divided by adobe berms into a grid of 30 cells, each 3,000 feet square, Chetro Ketl Field has been interpreted as an agricultural catchment field for rainwater runoff (in an area without natural streams). This remains unproven and, for practical reasons related to whether Chaco Canyon could ever have been agriculturally self-sustaining, now seems unlikely.

Perhaps the most unusual feature in “Downtown Chaco” is Tse’biinaholts’a Yałti (Rock that Speaks). Located at the geometric center of the Chaco Canyon core area, where it separates Pueblo Bonito from Chetro Ketl, Tse’biinaholts’a Yałti is situated in a natural alcove, semicircular in shape and 550 feet wide, and has been modified to have exceptional acoustical qualities. Evidence indicates that the area in front of the alcove was leveled and paved, and was perhaps used for performances or rituals.

Weaving through and radiating out from Chaco Canyon is a dense web of alignments called the Chacoan linescape, which connects archaeological sites, celestial phenomena, and geological formations. The linescape includes scrub lines (where surface material has been removed), grooves cut into bedrock, and sightlines indicated by walls, cairns, and posts. Formalized alignments, sometimes called roads, range from narrow paths to throughways 30 feet in width; in the largest examples, throughways may occur in two or more parallel lines. Surveys indicate that the Great North Road probably extended from Chaco Canyon at least to Aztec Ruins, 50 miles away, while the Great South Road terminates at Hosta Butte, a sacred landform located 34 miles to the southwest. There is no evidence to indicate that the roads were ever used for transportation, and what little cultural material has been found suggests that the roads functioned ritually in the cosmological realm.

During the early 1100s, construction began on the first-order great houses along the San Juan and Animas Rivers. By 1150, the center of the Chacoan Empire had probably moved to the new great houses at Aztec and Salmon, and building at Chaco Canyon ceased. The last of the first-order great houses—East Ruin at Aztec—dates from circa 1200, but around 1300, all of the Chacoan settlements were suddenly abandoned in a single event. The decline of the Chacoan Empire has been a subject of intense debate, and archaeologists still disagree about its source. Whether motivated by environmental, political, or even religious reasons, the people of the Four Corners region dispersed, leaving their monumental architecture to fall to ruin.

This National Park Services site is open to the public during regularly scheduled hours; there is a campground for visitors traveling to its remote location.

References

Crown, Patricia L. “Chocolate: Consumption and Cuisine from Chaco to Colonial New Mexico.” El Palacio 117, no. 4 (Winter 2012): 36-43.

Fowler, Andrew P., and John R. Stein. “The Anasazi Great House in Space, Time, and Paradigm.” In Anasazi Regional Organization and the Chaco System, edited by David E. Doyel, 101-122. Anthropological Papers No. 5. Albuquerque: Maxwell Museum of Anthropology / University of New Mexico, 1992.

Frazier, Kendrick. People of Chaco: A Canyon and Its Culture. Revised edition. New York: W.W. Norton, 1999.

Judd, Neil Merton and Glover M. Allen. The Material Culture of Pueblo Bonito. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1954.

Judd, Neil Merton. The Architecture of Pueblo Bonito. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1964.

Lekson, Stephen H. The Chaco Meridian: Centers of Political Power in the Ancient Southwest. London: Altamira Press, 1999.

Lekson, Stephen H. “Introduction.” In The Architecture of Chaco Canyon, edited by Stephen H. Lekson, 1-6. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2007.

Lister, Robert H. and Florence G. Lister. Chaco Canyon: Archeology and Archeologists. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, 1981.

Loose, Richard W. “Tse’Biinaholts’a Yałti (Curved Rock that Speaks).” Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness, and Culture

1, Issue 1 (March 2008): 31-50. Marshall, Michael P. “The Chacoan Roads: A Cosmological Interpretation.” InAnasazi Architecture and American Design, edited by Baker H. Morrow and V.B. Price, 62-74. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1997.

Nials, Fred. “Physical Characteristics of Chacoan Roads.” In Chaco Roads Project, Phase I: A Reappraisal Prehistoric Roads in the San Juan Basin, edited by Chris Kincaid, 6-1 to 6-51. Albuquerque: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, 1983.

Pepper, George H. Pueblo Bonito. New York: Trustees of the American Museum of Natural History, 1920.

Sofaer, Anna. “The Primary Architecture of the Chacoan Culture: A Cosmological Expression.” In The Architecture of Chaco Canyon,edited by Stephen H. Lekson, 225-254. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2007.

Stein, John R. “Road Corridor Descriptions.” In Chaco Roads Project, Phase I: A Reappraisal Prehistoric Roads in the San Juan Basin, edited by Chris Kincaid, 8-1 to 8-15 . Albuquerque: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, 1983.

Stein, John R., Richard Friedman, Taft Blackhorse, and Richard Loose. “Revisiting Downtown Chaco.” In The Architecture of Chaco Canyon, edited by Stephen H. Lekson, 199-224. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2007.

Stein, John R., and Stephen H. Lekson. “Anasazi Ritual Landscapes.” In Anasazi Regional Organization and the Chaco System, edited by David E. Doyel, 87-100. Anthropological Papers No. 5. Albuquerque: Maxwell Museum of Anthropology / University of New Mexico, 1992.

Stuart, David E. Ancient Southwest: Chaco Canyon, Bandelier, and Mesa Verde. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2010.