Sited on a windswept limestone hill overlooking a desolate plain, Gran Quivira was the southernmost and most marginal of the Salinas pueblos and missions. More than any other site, it speaks of the endurance required by native inhabitants and colonizers alike to live here in the seventeenth century.

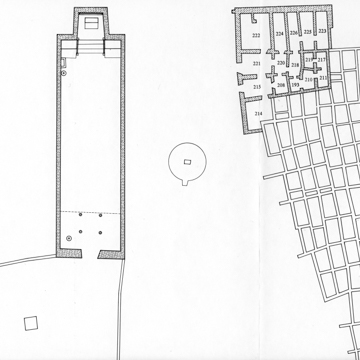

Settled by Tompiro Indians around 1300, the Pueblo of Cueloze preserves traces of the shallow basins and ditches dug out on the surrounding hill to capture sparse rainwater for dry farming in this harsh and arid land. The partly excavated pueblo was constructed in phases. Between 1300 and 1400, the Tompiro built a circular pueblo on the north side of the site. Centered on a plaza and kiva, its wedge-shaped rooms were built of local blue-gray limestone laid in a yellow clay mortar. Starting around 1550, they built a second, rectilinear pueblo atop the earlier one. The main housing block of 250 square rooms, built of the same limestone laid in a gray clay mortar, faces east onto a plaza with a great kiva. At its height in the seventeenth century, the pueblo numbered some 2,000 people.

The pueblo was renamed Las Humanas by the Spaniards, referring to the stripped facial decoration worn by the Tompiro. After Fray Alonso Benavides conducted a mass conversion in the main plaza in 1627, Fray Francisco Letrado, assisted by Fray Estévan de Perea, was assigned to missionize the pueblo in 1629. They moved into rooms in the southwest corner of the main block, which they expanded in 1630 with 8 new rooms to serve as a chapel and friary.

They also began work on the church of San Isidro, but soon realized that the lack of water made it difficult to support a proper mission. In 1631, Letrado recommended that Las Humanas become a visita of the mission at Abó and departed for the Zuni pueblo of Hawikuh, where he was killed in 1632. Perea stayed on until Las Humanas was made a visita in 1633. Fray Acevedo, the guardian of Abó, completed the church, now rededicated to San Buenaventura, in 1634–1635.

The church is located to the south, below the main housing block and friary, where it faces east toward a cemetery on a platform cut out of the sloped hillside. Like the first church at Abó, San Isidro was a single nave type, measuring 25.5 x 108 feet and without either transepts or a transverse clerestory. Its thin limestone walls, only 2 feet thick, rose 28 to 30 feet. The simple east facade, with a window and bell cote but no entrance porch, led inside to a choir loft and baptismal font. The church ended in a square chancel and trapezoidal apse, with lower side altars flanking a raised high altar. In 1979, Gordon Vivian suggested that parallel rows of wooden posts might have been added to help support the vigas spanning the nave, creating side aisles, though this possibility has since been questioned by James Ivey.

A kiva stands along the northern flank of San Isidro. While it is unclear whether this kiva was built before or at the same time as the church, their proximity and the likelihood that they were in use concurrently suggests that the friars tolerated the native religion, at least initially.

In 1659, as part of a missionary resurgence in New Mexico, Las Humanas was restored in status as a mission and Fray Diego de Santandér was made its guardian. Work began on a new church and friary of San Buenaventura in 1660. Located west of the pueblo and oriented east like San Isidro, San Buenaventura and the friary to its immediate south border a large open plaza across from the main housing block. Effectively, the church and its plaza constituted a countervailing Christian space to the original plaza with its great kiva on the pueblo’s opposite side.

The absence of a kiva in the friary, like those found at Abó and Quarai, along with signs that rooms in the pueblo were being adapted to serve as hidden kivas, suggest that doctrinal rigidity was replacing the friar’s earlier tolerance of native religious practices. A contributing factor might have been the increasing dissension between the civil and religious authorities. The provincial governor was encouraging the pueblos to assert their jurisdictional independence from the Franciscans, and had identified Santandér as one of a troublesome group of activist friars.

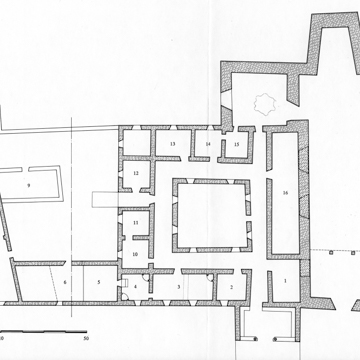

The new single-nave church of San Buenaventura had transepts ending in a deep trapezoidal apse, and probably a planned transverse clerestory. Its stark facade, like that of San Isidro, had a central portal, window, and possible bell cote, but no porch. Inside, the choir loft connected to a separate baptistery on the right. The south transept leads to a large square sacristy, nearly as wide as the nave.

The steeply sloping hillside site necessitated a substantial platform, with 8-foot-high retaining walls to the north and west, and 6 feet high to the south. Difficulties encountered in leveling this site could explain the church’s irregular footprint. The nave, 109 feet long, narrows from 29 feet 10 inches at the entrance to 26 feet 10 inches at the transepts, a difference in width of 3 feet that was more likely the result of poor surveying than an optical refinement of forced perspective as hypothesized by George Kubler. And the pronounced slope of the church floor, which drops nearly 4 feet over the same distance, was also the likely result of mistakes in erecting the retaining walls to a uniform level.

The square friary, which was altered during construction, was entered at its northeast corner through a vestibule porch (porteria); the refectory, kitchen, and friars’ cells opened directly off the central walkway (ambulatorio) and patio. An enclosed corral lay to the south, at a slightly lower level and reached through a corridor from friary.

Santandér planned and started the church and friary before he was reassigned to another pueblo in 1662. The unnamed friar who succeeded him completed most of the friary between 1663 and 1666, but left the church no more than half built. Fray Joseph de Parede replaced this friar late in 1666. In the midst of the worsening drought and famine, which killed 450 members of the pueblo in 1667, work on the mission continued fitfully until 1670. Despite some evidence to the contrary, it is generally believed that the church was never finished; its limestone walls, 5-6 feet thick, rise irregularly to 15-20 feet, and the nave was left open to the sky. At Las Humanas, the monumental ambitions of the Franciscans collapsed in a fateful combination of political conflict, cultural difference, and environmental catastrophe.

San Isidro continued to serve as the mission church, until it was burned in September 1670, during an Apache raid that also destroyed the original friary in the pueblo’s main block. A short time later, Las Humanas was abandoned and never reoccupied. The natural depredations of time were exacerbated by scavengers, and by treasure hunters who undermined the ruins in their search for buried wealth: around 1835, the pueblo was mistakenly identified as Gran Quivira, one of the mythical seven cities of gold that had lured Francisco Vásquez de Coronado to New Mexico in the sixteenth century. No treasure was found, but the name of Gran Quivira stuck. Major campaigns of archaeological excavation and stabilization were undertaken in throughout the twentieth century.

This National Park Services site is open to the public during regularly scheduled seasonal hours.

References

Ivey, James E. “In the Midst of Loneliness”: The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions. Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 15. Santa Fe: National Park Service, 1988.

Kubler, George. The Religious Architecture of New Mexico In the Colonial Period and Since the American Occupation. 1940. Reprint, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1972.

Treib, Marc. Sanctuaries of Spanish New Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Vivian, Gordon. Gran Quivira: Excavations in a 17th-Century Jumano Pueblo. Archeological Research Series No. 8. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1979.