Harlem’s most important commercial street and its de facto “Main Street,” 125th Street runs east-west from the Hudson River to the East River on the island of Manhattan. It is also known by its honorific name, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd. The character and history of 125th Street in many ways mirrors the history of New York as a whole: a city founded in commerce, attracting migrants from around the world, and growing under great demand for real estate.

The inauguration of the Erie Canal in 1825 made New York the country’s most important port city along global trade routes; it also made the canal a model for projects across the United States. The following year, Scottish immigrant Archibald D. Watt determined that he would build his own canal following a creek over a fault line on his 300-acre Harlem farm, with the goal of connecting Harlem and the Hudson River. Work on the canal was left incomplete, but its start formed what would become 125th Street.

Canals were quickly surpassed by railroads as a preferred transportation method, and in the 1837 the horse- and steam-pulled New York & Harlem Railroad opened: the first suburban train line in America. At the time, Harlem was a 200-year-old village, first settled as an outpost on the Indian frontier as a line of defense for the city of New Amsterdam growing at the southern tip of Manhattan. The English takeover of the colony in the late seventeenth century led to the Anglicization of architectural styles, with large Federal and Greek Revival mansions built in Harlem. A full platting of Manhattan’s streets—Harlem included—was laid out in the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, touching off a long-lasting, speculative real estate market. When the New York & Harlem Railway line opened, passengers eagerly loaded trains from two directions: New Yorkers visiting a favorite bucolic place of retreat from the city and Harlem commuters boarding trains to work jobs in the city.

For New York and Harlem wealthy social elites, Harlem became an entertainment center for which several notable buildings were constructed. Harlem Hall opened on East 125th in 1870 and Oscar Hammerstein’s Harlem Opera House opened in 1889 at 207 West 125th, seating 1,800 audience members. Hammerstein opened a second theater on 125th Street—the Columbus Theatre—in 1890. Both Hammerstein theaters were financial losers, and the establishments were later converted into vaudeville halls. In 1914, Hurtig and Seamon’s New Burlesque Theater, designed by architect George Keister, opened at 253 West 125th. In 1934, under a change in ownership, it became the legendary Apollo Theater, which operated first as a Black vaudeville house and later as stage for the country’s most famous Black musicians and entertainers.

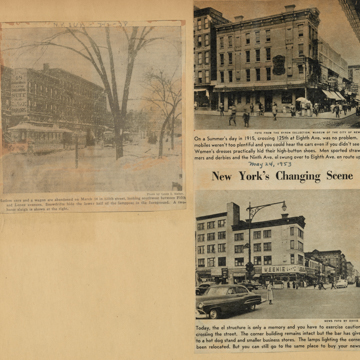

Three elevated rail lines opened with faster service between New York and Harlem in the late 1870s. In 1875, Harlem received a new station sunk below ground at 125th Street, spawning the street’s commercial development. At 81-85 East 125th, architects Hugh Lamb and Charles Alonzo Rich designed the red sandstone, Romanesque Revival Mount Morris Bank (with apartments above) in 1884–1885. A 12-story office tower—Harlem’s highest—was built at 125th and Park Avenue. In 1903, the terra-cotta and white-glazed tile Sheffield Pure Milk bottling plant opened on the street. In 1904, the McKim, Mead and White–designed, Carnegie-endowed, Renaissance Revival branch of the New York City Library was built at 224 East 125th.

At the turn of the twentieth century, fueled by real estate market frenzy, New York was rapidly expanding northward and building styles shifted in favor of town houses for the growing middle class. The 1890s also marked the beginning of the era of great migration to the north by African Americans from southern states. In New York, African Americans joined a confluence of immigrants from Europe and the Caribbean. The concentration of African Americans living in Harlem over the next fifty years was largely the result of racism as reflected in housing, schools, and jobs, as well as personal choice. 125th Street became a line straddling Harlem’s ethnic divisions—with Irish, German, and Italian immigrants settling in tenement buildings southeast of the street, and Jewish and African American migrants settling southwest and north of the street. When World War I interrupted migrations by Italian and Jewish people, African Americans became the largest group in Harlem, also known as “Black Manhattan.”

In Harlem, Black cultural heritage and Black pride took center stage. Thousands gathered in the street for a silent march against racism in 1917. Clubs and cabarets were at full swing with ragtime-evolved jazz music and dancing. The atmosphere fostered the development of poets, artists, and playwrights who drove an outpouring of creative expression known as the Harlem Renaissance—a cultural movement based in both modernism and memory.

Apartment buildings replaced town homes as the most commonly constructed housing in Harlem in an attempt to keep pace with demand. Nevertheless, demand for housing continued to rise. Landlords (predominantly white) could charge increasingly higher rents for increasingly lower quality accommodations, leading to the beginning of urban decay in Harlem. Shut out from white neighborhoods and thus nowhere else to go, Harlem residents slid increasingly into poverty.

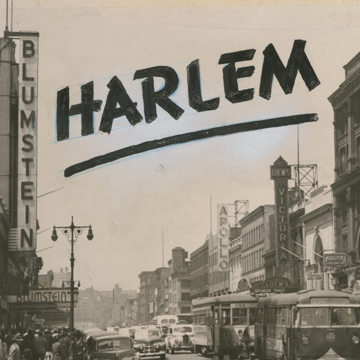

The Great Depression of the 1930s hit African Americans particularly hard, as white laborers filled jobs formerly dominated by Black workers. Prominent 125th Street businesses, such as Blumstein’s Department Store at 230 West 125th, maintained whites-only employment policies and discriminated against African American customers. As a result of a “don’t buy where you can’t work” boycott organized in 1934 by Effa Louise Manley, the Citizens League for Fair Play won a suit against the store, forcing them to hire African Americans. Activism continued in the streets and in 1935, 5,000 people took to 125th Street in protest of rumored brutality after the killing of a 16-year-old-shoplifter.

Beginning in 1940 and continuing over the next two decades, the 13-story, steel, white brick- and white terra-cotta–faced Hotel Theresa, on 125th between Seventh and Eighth avenues, became a significant social center of the African American community. The building was constructed in 1912–1913, but did not end its “whites-only” policy until 1940, when it was suffering financial duress. The Theresa had both permanent and temporary residents, but the apartments did not have full kitchens, so most residents ate in a common dining hall, where they mingled with one other and with visitors. Many famous and socially engaged people met and organized in the Theresa, including Joe Louis, Grace Johnson, Florence Murray, Malcolm X, and Langston Hughes.

Outdoors in Harlem, particularly corners of 125th at Lennox and Seventh avenues, became known as “The Street Corner University,” spawning speeches and debates by Malcolm X and others, who led marches down 125th Street. As Gilbert Osofsky has argued, racism and economics historically excluded Black residents from much of the city, and as Black neighborhoods expanded beyond their original boundaries, African Americans took advantage of the 1904 real estate bust in Harlem. This was successful for a short period as more Black people moved to Harlem to live in the housing, but high rents and low wages put stresses on the neighborhood. Consequently, the community declined due to the housing and the lack of sustained urban sanitation as well as the practices of racist landlords.

Furthermore, economic recessions of the 1970s and 1980s left the neighborhood (and much of New York as a whole) in disrepair and plagued by social problems. There were a number of efforts to revitalize the community. In 1986 Calvin O. Butts, a minister in the Abyssinian Baptist Church, asked his congregation to help in a community effort to rebuild Harlem. In 1989 they founded the nonprofit Abyssinian Development Corporation (ADC). As an organization, the ADC acquired and renovated significant numbers of apartments and is noted as Harlem's third-largest landlord, after the New York City Housing Authority and Columbia University. In addition to permanent housing, they led efforts to develop homeless shelters. They also oversaw the construction of public schools, set up after-school programs and services for seniors, and developed job training programs for Harlem residents. The organization brought a Pathmark supermarket to Harlem in 1997, which many consider the catalyst for the rejuvenation of 125th Street.

Since the late 1990s, Harlem has produced a second, cultural asset–based renaissance. In the 1990s, Geoffrey Canada established the Harlem Children’s Zone at 35 East 125th to support Harlem’s families and help them address social and infrastructure problems to improve health and well-being. The Harlem Children’s Zone has grown, spreading its programs over 97 blocks of Harlem and has inspired communities around the world. In 2007, the American Planning Association proclaimed 125th Street one of the ten greatest streets in the United States. Because of its well-preserved buildings, walkability, and liveliness, Harlem has become one of the most desirable neighborhoods in New York, subjecting the neighborhood to waves of gentrification.

References

Adams, Michael Henry, and Paul Rocheleau. Harlem, Lost and Found: An Architectural and Social History, 1765-1915. New York: Monacelli Press, 2002.

Crowder, R. “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work: An Investigation of the Political Forces and Social Conflict within the Harlem Boycott of 1934.” Afro-Americans in New York Life and History 15, no. 2 (1991): 7-44.

Crowder, Ralph. “The Historical Context and Political Significance of Harlem’s Street Scholar Community.” Afro-Americans in New York Life and History 34, no. 1 (2010): 34-71.

“Harlem's 125th Street: New York, New York.” Great Places in America: Streets. American Planning Association, 2007. https://www.planning.org/.

Dolkart, Andrew Scott. “Hotel Theresa.” New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, Designation List 252, LP-1843, July 13, 1993.

Dolkart, Andrew Scott. “Mount Morris Bank Building.” New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, Designation List 248, LP-1839, January 5, 1993.

Noonan, Theresa C. “The New York City Library, 125th St. Branch.” New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, Designation List 409, LP-2305, January 13, 2009.

Osofsky, G. Harlem, the Making of a Ghetto: Negro New York, 1890-1930. 1st ed. New York: Harper and Row, 1966.

Tritter, Thorin. “The Growth and Decline of Harlem's Housing.” Afro-Americans in New York Life and History 22, no. 1 (1998): 67.

Weil, François. A History of New York. Columbia History of Urban Life. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.