From its opening in 1825 through the early twentieth century, the Erie Canal played a central role in the growth of New York State and the nation as a whole. The canal originally stretched 363 miles from Albany to Buffalo, linking the Hudson River to the Great Lakes and enabling people and goods to move more efficiently from the East Coast to the Midwest. The resulting industrial and tourist activity brought unprecedented economic development to New York State and increased westward migration, prompting significant population growth in the Midwest and beyond. The canal also left its mark on engineering in the U.S. Its design and construction involved a number of technical experiments and notable innovations, and provided an informal training ground for an emerging profession.

In 1808 New York City Mayor Dewitt Clinton began promoting the Erie Canal project hoping the federal government would fund its construction. In 1817, after repeated congressional refusals, Clinton—by then governor of the State of New York—convinced the state legislature to fund the “big ditch” as the canal was known colloquially. The canal’s route was determined partly by geographic restrictions, but also through political and economic strategy: though an easier path from the Hudson to Lake Ontario existed, that would have directed commerce towards Montreal; routing the canal to Lake Erie, by contrast, ensured that it would primarily benefit New York State. The state acquired lands for the canal through direct purchase and through land grants by owners of large tracts who stood to profit from the canal’s construction.

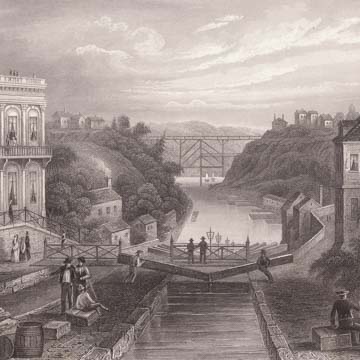

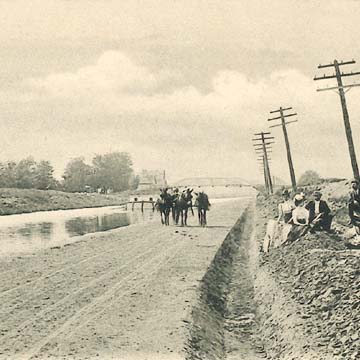

Under the direction of Benjamin Wright, chief engineer of New York State Canals, the Erie Canal was designed to be 4 feet deep and 40 feet wide, with a towpath on one side. Building the canal bed involved significant clearing and digging, as well as reinforcing the waterway’s base and sides using regionally sourced materials like limestone blocks for aqueduct structures and clay for canal lining. The Canal Commission also funded significant research and experimentation, including the engineer Canvass White’s work with mortars for underwater use. White invented a limestone-based hydraulic cement that was used as mortar not only in the Erie Canal, but in numerous other construction projects. Negotiating changes in elevation along the route necessitated a series of locks, bridges, and aqueducts: 83 locks were built to negotiate a total rise of 568 feet between the Hudson River and Lake Erie, and 32 aqueducts were built to pass over existing waterways.

At an average of 4 miles per hour, the speed of travel on the Erie Canal was a vast improvement over other forms of inland transportation. As a result, in the years following the canal’s opening, New York State boomed with industrial and agricultural development. The port of New York City grew dramatically, becoming the major site for trade between the East Coast and the Midwest. Populations exploded in Albany, Buffalo, Rochester, Utica, and smaller towns along the canal route. Spur canals such as the Seneca and Oswego further knit the canal system into the rural fabric of the state, providing water-based connections to towns such as Seneca Falls and Ithaca. Stagecoach and train lines connected many rural villages to canal stops; as a result, mills, dams, and factories were built in once remote but now newly accessible areas, providing income and electrical power to small communities. The canal catalyzed growth further west as well. Because both goods and people could travel westward with greater ease than ever before, migration increased, particularly to the Great Lakes region.

As it grew in economic power, the canal also gained cultural currency. A canal-based tourist industry grew, with East Coast inhabitants riding canal boats to see the waterfalls and lakes of New York State. Firsthand accounts, such as Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1835 “The Canal Boat,” although sometimes critical of the slow pace of travel and the canal’s industrial character, nonetheless helped to popularize such excursions. At the western terminus of the Erie Canal, Niagara Falls became a “must-see” destination on a Northeastern Grand Tour, with tourists traveling via the canal to reach the falls. Tourists visiting this mix of natural wonders and novel manufactories, returned with accounts of romantic wilds and manifestations of American ingenuity.

For more than a century after its initial construction, the Erie Canal underwent numerous improvements, enlargements, and extensions, always with the aim of extending its usability. Between 1836 and 1862, the canal was deepened to 7 feet and widened to 70 feet. Between 1903 and 1918, it was enlarged yet again and linked with other state canals, along with an additional 32 locks. Despite this work, this period also saw a steady decline in canal use for commercial shipping. The growth of railroad networks drew passengers away from the canals as early as the 1830s; the formerly preeminent canal boats could not compete with the speed of locomotives. Nonetheless, commercial transport on the canal remained fairly steady until the 1950s, when trucking on the expanding highway network finally rendered canal-based transport all but obsolete. Though modest commercial shipping continued until the 1990s, the canal was increasingly used as a recreational corridor until the first decade of the twenty-first century, when commercial shipments began a modest uptick.

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the economics of central and western New York State were tied to the Erie Canal, which created new geographies of commerce, even as shifting demands eventually transformed it from a largely industrial infrastructure into a recreational one. In the twenty-first century, the Erie Canalway is a National Heritage Corridor devoted almost exclusively for recreational touring. Due to successive renovations, few traces of the early 1800s canal still exist. Remains of early locks can be seen from the Erie Canalway Trail and at the Schoharie Crossing State Historic Site in Fort Hunter. In Lockport, the innovatively engineered locks from the mid-1800s have been restored. Some remnants of mid-1800s aqueducts are extant, including Old Richmond Aqueduct in Montezuma and the Schoharie Creek Aqueduct in Fort Hunter.

References

Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor. “Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor.” Accessed September 1, 2015. http://www.eriecanalway.org.

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. “The Canal Boat.” New-England Magazine 9 (1835): 398-409.

Maag, Christopher. “Hints of Comeback for Nation’s First Superhighway.” New York Times, November 2, 2008.

Penner, Barbara. Newlyweds on Tour: Honeymooning in Nineteenth-Century America. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2009.

Shaw, Ronald E. Erie Water West: A History of the Erie Canal, 1792–1854. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2013.

Stradling, David. The Nature of New York: An Environmental History of the Empire State. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2010.

Whitford, Noble E. History of the Canal System of the State of New York. Albany: Brandow Printing Company, 1906.