The Greenfield Exempted Village School campus came to national attention in 1915 as a leader in the progressive schools movement, which was remarkable because it was located in a rural Ohio village of 6,000 people. Eighty-five years later it would again receive national attention as an award-winning example for school restoration/renovation.

In 1912 a local philanthropist, Edward Lee McClain, who made his fortune as the inventor and manufacturer of an improved horse collar, donated $500,000 to his community for a state-of-the-art high school. Edward and Lulu McClain, along with Greenfield school superintendent F.R. Harris, were promoters of progressive education, which emphasized the arts, nature studies, science, health, social living, and physical education in addition to the basics of reading, writing, and mathematics. They hired William B. Ittner of St. Louis, Missouri, a leader in educational architecture, to assist them in the development of an educational facility that would serve as a national model for both large and small school systems. They believed that placing students in an elegant and artistic environment would produce citizens of the highest quality; they also thought that education should be practical. The elegance was achieved in a series of Georgian Revival structures and carefully planned landscaping; the practicality was achieved in modern facilities that contained classrooms and workshops to prepare students for both college and vocational trades. Due to its innovations, the building and campus were published in over fifteen journals, including a 1922 Bureau of Education bulletin.

Thanks to Edward McClain’s donation, the three-story high school opened in 1915. Thanks to his wife Lulu McClain, the school included a 160-piece art collection of murals, paintings, lithographs, copies of classical sculptures, photographs, reproductions of paintings, and original tile work selected for the building by Theodore M. Dillaway, Director of Arts Education in Boston and later Philadelphia. The collection featured themes deemed appropriate for the edification of youth. Lithographs include all fifteen panels of Edwin Austin Abbey’s Quest of the Holy Grail, reproductions of works by Rembrandt, Stuart, and Violet Oakley, casts of classic sculptures from Egypt, Greece, Rome, and from the Renaissance, as well as original photographs. In 1928, Superintendent William G. Moler supplemented the collection with a donation of the original 1837 marble bust of Ginevra by Hiram Powers.

The Edward Lee McClain High School, the first building completed, was designed around a central courtyard. The building is accented with Moravian tile panels and stone balustrades, and the main entry displays a frontispiece crafted from Bedford stone with double Ionic pilasters flanking a double, multi-paned doorway beneath a tripartite, multi-paned, second-story window. The entry corridor features a marble stair with an original mural, Apotheosis of Youth, by Boston artist Vesper Lincoln George; two more George murals are located in the top floor library. A reproduction of the frieze for the Parthenon decorates the corridors. The porcelain drinking fountains have Rookwood Pottery tile backsplashes. The 1,000-seat auditorium, which has a pipe organ from the Ernest M. Skinner Company of Boston, was designed to serve the school and the community. Science laboratories, lecture halls, a tea garden and volleyball courts on the roof, home economics rooms for cooking and sewing, a practice dining room to teach entertaining skills, locker rooms, a health clinic, and offices were also located within the building.

With the opening of the high school, the community approved a $400,000 levy to construct the Greenfield Elementary School, which was completed in 1924 by Ittner. It was designed to accommodate the “platoon” system of education in which students spend half of their time in traditional classroom instruction and the rest of the day in nature studies, handiwork, physical education, home hygiene, health studies, music, and art. The building was designed with single-loaded corridors that had large, operable windows in order to improve natural lighting and healthy airflow in the classrooms. The building contained a library, auditorium, gymnasium, and clinic. Lulu McClain also donated tile work and art for this building.

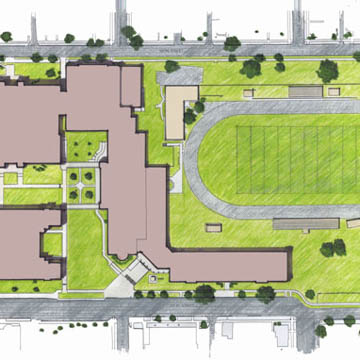

The campus included an athletic field and stadium (1923), vocational school and natatorium (1924), and a landscaped courtyard, fountain, and pergolas connecting the main buildings, all designed by Ittner. The village was too small to have a large enough student body for the campus, so the district was expanded to include 100 square miles. The concept of consolidation of small districts was also part of the progressive moment. At the time, school officials believed that centralization would improve quality while reducing cost; to achieve this, they implemented a bus system for transporting students and Ittner designed the transportation garage in 1933. In 1960, the one-story Duncan McArthur Elementary, designed by Howard and Thomas J. McClorey from Cincinnati, was built and in 1970 a gymnasium was added to the high school.

Following a lawsuit from economically disadvantaged school districts, the State of Ohio passed a funding initiative in 1997 to replace aging school facilities and the Greenfield Campus was designated for total replacement. The Board of Education and the community were forced to decide between all new schools or maintaining their beloved but aging facilities. Clyde Henry of TRIAD Architects, working closely with Phil Cornette, the district’s superintendent, developed a plan that met all of the state’s requirements, while maintaining and restoring the historical facilities at a lower cost than new construction. While the state was initially skeptical of the plan, it had the community’s overwhelming support, and was ultimately accepted. The renovation maintained the open corridors, high ceilings, and grand stairs; it also hid all the new ductwork for the new heating and air conditioning systems and the electrical and computer network cables, while adding hidden indirect lighting, elevators, and other code requirements. A second floor was added to the Duncan McArthur Primary Building and the existing first floor was covered in matching brick. The fenestration, details, and scale of the building were brought into line with the other buildings on the campus.

The high school was also expanded at this time, with an addition that covered the north facade of the 1970 gymnasium and brought it into conformity with the campus. The project proved that historical buildings could be renovated to serve current and future needs without sacrificing either the historical fabric or the required educational programing. The project won the National Trust Preservation Award of Excellence for renovation, and has served as an example of award-winning school restoration/renovation.

References

Lewis, Gould L. The Progressive Era, 1890–1914. New York: Routledge, 2013.

McCormick, Virginia E. Educational Architecture in Ohio, From One-Room Schools and Carnegie Libraries to Community Education Villages. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2001.

Reese, William J. Power and Promise of School Reform: Grassroots Movements during the Progressive Era. New York: Teachers College Press, 2002.