Spanning nine states and thousands of miles, the Trail of Tears represents the collection of routes taken by more than 16,000 Cherokee tribespeople, and about 1,600 people of African descent they had enslaved, as they were forced to emigrate from their ancestral lands in the Southeastern United States to reservation land in Oklahoma in 1838 and 1839. Most of the original land and water routes taken by the Cherokee across Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Tennessee are maintained as the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, which is administered by the National Park Service along with the Cherokee Nation, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the Trail of Tears Association, private landowners, and local, state, and national governments. The National Historic Trail was designated in December 1987 through an amendment to the National Trails System Act and consists of more than 2,200 miles of land and water routes that pass through a number of maintained historic sites and memorials marking the forced migration of the Cherokee. Though other tribes including the Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, and Chickasaw where forcibly removed from their lands during the 1820s and 1830s, the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail specifically commemorates the Cherokee migration.

The Cherokee historically occupied a large swath of the southern Appalachian Mountains. Living in villages in present-day Kentucky, West Virginia, Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, and Georgia, the seven tribes of the Cherokee Nation inhabited tracts of fertile, resource-rich lands that were attractive to white settlers moving to the region during the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries. In 1825, President James Monroe approved John C. Calhoun’s plan for the Indian Removal Act, which would compel all Indian people east of the Mississippi to cede their lands to the United States government and move west to “Indian Territory” in present-day northeastern Oklahoma. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson and the federal legislature put the act into motion, utilizing military force to remove thousands of Creek, Seminole, and Chickasaw people from their lands to await the long journey to Oklahoma in stockades and ill-equipped internment camps.

The United States Army invaded Cherokee land in 1838, empowered by the Treaty of New Echota, negotiated in 1835 and heavily protested by the Cherokee people. The treaty transferred all traditional Cherokee lands to the federal government in exchange for monetary compensation and relocation assistance. Thousands of Cherokee signed a petition protesting the treaty, but it was approved by Congress and the Cherokee were forced to abandon their lands, relocate to internment camps in southeastern Tennessee, and then embark on the treacherous journey west.

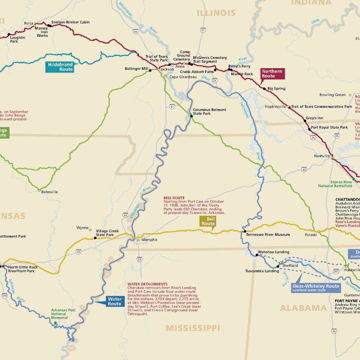

The first large group to depart on the journey traveled primarily by boat, departing from Waterloo, Alabama, and Chattanooga, Tennessee, to travel down the Tennessee River, continuing along the Ohio, Mississippi, and Arkansas rivers to reach Fort Smith, Arkansas, near the Oklahoma border. Hundreds died from disease and exposure along this route, which was made more difficult by lower water levels. The majority of Cherokee who migrated to Oklahoma during forced removal traveled along the northern route, which began in Charleston, Tennessee, and ended in Indian Territory in Oklahoma. This overland route angled northwest through Nashville and western Kentucky before continuing west across southern Illinois and meeting the Mississippi River north of Cape Girardeau. In order to avoid the Ozark Plateau, the route shifted northwest again, eventually passing through Springfield, Missouri, and Fayetteville, Arkansas. By the time this group of Cherokee reached Oklahoma, they had walked almost 1,000 miles and lost a quarter or more of their people along the way. Hundreds died shortly after reaching Oklahoma. The devastating journey became known for the Cherokee as Nunahi-Duna-Dlo-Hilu-I, or “the trail where they cried.”

Today, the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail closely marks the original routes taken by the Cherokee during their forced migration, and seeks to preserve sites, artifacts, and narratives that surround that journey and its cultural significance both for the Cherokee people and the nation more broadly. Working with the Cherokee Nation and other tribal and conservation groups, the National Park Service developed a management plan that is overseen and implemented by the Long Distance Trails Office headquartered in New Mexico. A coalition of groups continues to work to maintain the trail and provide interpretive programming to increase awareness and understanding around this historic tragedy.

References

Gaines, David M., and Jere L. Krakow. "The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail." Landscape and Urban Planning 36.2 (1996): 159-169.

King, Duane H., and E. Raymond Evans, eds. “The Trail of Tears: Primary Documents of the Cherokee Removal.” Journal of Cherokee Studies 3 (Summer 1978): 131-190.

Perdue, Theda, and Michael D. Green. The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears. New York: Penguin Group, 2007.